Shop

What Do 17.77 Tallboys of Pilsner Urquell, Six American Brewers, and One Bus Have in Common?

Most-Read Stories Right Now:

It’s 8 o’clock in the morning somewhere in Czechia.

Six well-respected American brewers pile on to a bus—Peter Kiley, brewmaster at Monday Night Brewing; Shawn Bainbridge, co-founder of Halfway Crooks; Ryan Murphy, lead brewer at Schilling Beer Co.; Eric Larkin, co-founder of Cohesion Brewing Co.; Khris Johnson, head brewer and co-founder of Green Bench Brewing Company; and Ben Peterson, lead brewer at Threes Brewing.

As this collective group of savants steps inside, a man from the Embassy of Czechia to the USA hands them a Pilsner Urquell, one of the most ubiquitous pilsners in Czechia.

Without question, they all start drinking.

For the next five days, the group would imbibe an epic amount of Pilsner Urquell (sometimes Budvar 33) on that bus. It’s a memory they all recounted to me with utter clarity (despite the copious liquid consumed).

“Every day was a professional hair of the dog,” laughs Bainbridge.

Kiley jokingly told me that hair of the dog would be beer number one of the 17.77777 they drank daily.

“We were inundated with Pilsner Urquell from sunup to sundown; it was everywhere,” says Larkin.

Part of a five-day trip sponsored by the Embassy of Czechia to the USA and Canadian ingredients importer Hop & Stuff, these six brewers immersed themselves in Czech beer culture on a whirlwind trip.

They all learned one thing pretty quickly: The Czechs LOVE beer.

Need proof? Well, for the last twenty-eight years, the people of Czechia have consumed the most beer per capita out of any country in the world. In 2020, Czechs drank 181.9 liters per person ???? (Kirin Holdings). For context, the United States ranked seventeenth with only 72.8 liters per person.

Suffice it to say that the Czechs take their beer seriously. And for the first time in centuries, they’re finally sharing their beer culture with the world.

Bussing Around Czechia: Part Mission Trip, Part Summer Camp

Green Bench Brewing Company Co-Founder Khris Johnson outside the bus in Czechia | Photography courtesy of Shawn Bainbridge | Halfway Crooks Beer

With the goal to bring American and Canadian brewers to the country to learn about Czech beer, ingredients, and culture, this mission takes like-minded individuals in the industry on a jam-packed tour.

“I see a lot of ways you can get isolated in a bubble,” says Murphy. “[The trip] exposed me to things I couldn’t… To be with people who have a similar point of view but different backgrounds and knowledge sets was so rewarding.”

Led by Agricultural Attaché at the Embassy of Czechia to the USA Petr Ježek (who Kiley affectionately referred to as the patriarch, guide, teacher, and ring leader), the highly stimulating trip whisked these brewers all across the country, visiting manufacturers, producers, and breweries like Pilsner Urquell.

The preferred mode of transportation? A big ol’ team bus.

“It was an intensely packed trip, and the amount of time we spent on the bus was insane for one week,” says Larkin. “We stopped [only] for cigarette breaks and bathroom breaks.” Well, and maybe to buy more Pilsner Urquell.

With sometimes hours between stops, the bus became more than just getting from one place to another. Forced into a confined setting, these six talented brewers swigged beers while swapping stories, talking shop, occasionally singing, and discussing things like race, representation, sexism, and inclusivity.

They bonded over what Kiley calls a “low-grade collective trauma of having a warm Pilsner Urquell tallboy in the morning after aggressive consumption the previous day.”

Especially since, Kiley says, you couldn’t show weakness around Ježek, who became known for repeatedly yelling “five minutes” at everyone to finish their beer before they had to leave. “Towards the end of the trip, we diagnosed him as tricking us into drinking beer quicker,” laughs Kiley.

Photography courtesy of Peter Kiley | Monday Night Brewing

When all six returned to the States after their “craft beer summer camp” (so dubbed by Kiley’s wife—Rachel Kiley, COO at Monday Night Brewing), they knew they wanted to find a way to pay homage to what they learned and experienced in Czechia.

Because sure, politically, this mission introduced American and Canadian brewers to Czech producers, ingredients, and beer styles. But perhaps inadvertently (or not), drinking Pilsner Urquell together on a bus showed these Western beer folk something else.

Something hard to quantify.

The extraordinary camaraderie of a very historic Czech drinking culture. One few outside of the country understand.

So, of course, this fun group of beer minds had to try, recently releasing the aptly named Bus Beer, a Czech-style pale lager pay homage to what brought them all together.

“We now carry that torch of knowledge,” says Kiley. “We wanted to honor the traditions…but also the trip, the memories, and the experiences we shared together.”

A Very Brief, Complicated History of Beer in Czechia

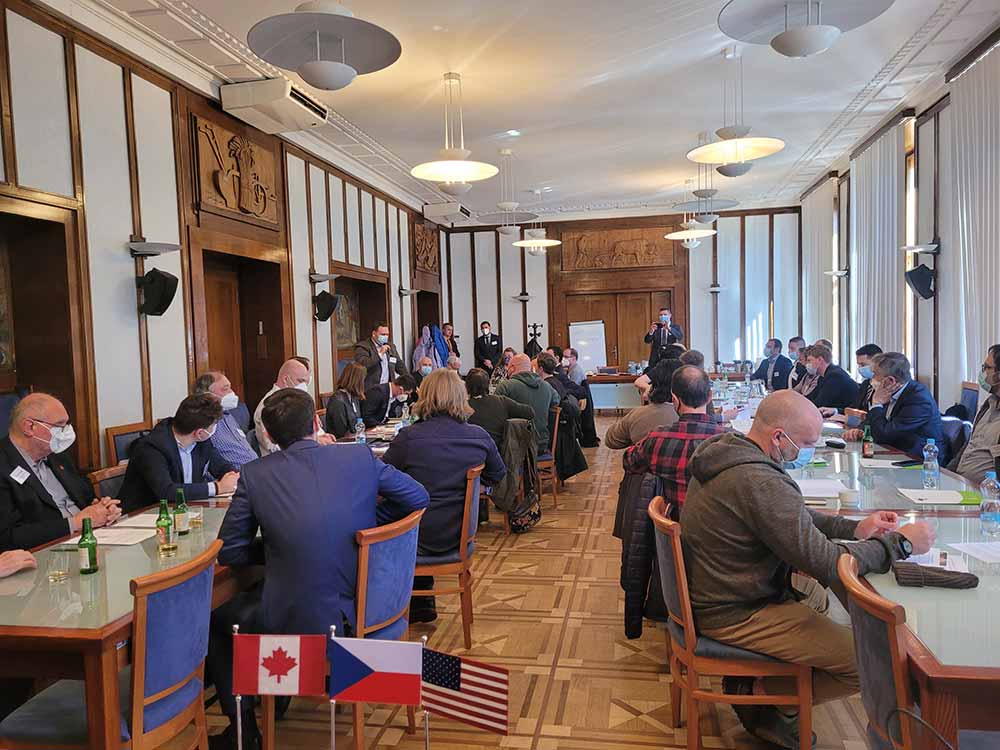

Every year the Czech Embassy and Canadian importer Hops & Stuff run a mission trip to Czechia to give Canadian and American brewers a chance to learn about Czech beer culture, ingredients, and production. | Photography courtesy of Peter Kiley | Monday Night Brewing

To fully understand Bus Beer, you need to understand what drives Czech beer.

The Czechs have a long, tangled history with beer production. According to Larkin, many of the breweries they visited on the trip had existed since the 1300s, 1400s, or even 1500s. “They’ve been making beer for so long; it’s hard to replicate that here in the U.S.,” he says.

But over the twentieth century, both the Nazis and Russians occupied Czechia, making conditions less than ideal. The Czechs had to adapt just to survive.

“The situation in our country was de facto unchanged after 1948, with exceptions, individualities did not arise, logically it was not possible in the communist regime, any individuality was suppressed there,” wrote Pilsner Urquell Master Bartender Champion Lukáš Svoboda in an email to Hop Culture.

From a brewing perspective, Czechs couldn’t push exports or promote their beer culture.

For instance, Bavarian brewery Josef Groll first brewed a pilsner in Plzeň, Czech Republic, in 1842. Technically, the word pilsner means “from Pilsen (or Plzeň)” in Czech. And if you say Piju Plzeň in Czech, that directly translates to “I’m drinking the town of Plzen.”

Today, the style has become one of the most widely consumed worldwide (even Miller Lite cans include the word “pilsner” on them). But while millions of people drink the style, far fewer recognize what the word “pilsner” means and where this beer style originated.

Photography courtesy of Shawn Bainbridge | Halfway Crooks Beer

In other words, the Czechs invented one of the most-drunk global beer styles but haven’t received equal recognition.

“They could have held onto that and proliferated their name and culture across the world for beer, but they didn’t get that opportunity because they were oppressed,” says Larkin, who fell in love with Czech beer in 2018 on his honeymoon to Prague and has made it his life mission to respect Czech drinking traditions at Cohesion Brewing in Denver, CO.

Compare this lack of awareness to other European countries. For example, in France, the government heavily controls the appellation for Champagne and Cognac; in Germany, the Cologne region controls the appellation for Kölsch.

No regulations or official recognitions exist for pilsner.

“It’s way too late now for the Czechs,” says Larkin. “But if we can pay homage to that beer culture and what they did for beer styles around the world, I think that’s a small part of what we’re excited about doing.”

A small part of a tall order.

Because in Czechia, you need to understand that pilsner and Czech pale lager are the same things…and yet very different.

What Is the Difference Between Pilsner, Pilsner Urquell, and Czech Pale Lager?

Photography courtesy of Peter Kiley | Monday Night Brewing

When the sextet set out to brew Bus Beer, the first consideration had to be what style to make.

It didn’t take long for them to agree that it had to be like the beer they repeatedly drank on the bus—Pilsner Urquell, a pilsner…and yet also a Czech pale lager.

Let’s explain.

In Czechia, there are actually very few different styles of beer—pale (světlé), amber (polotmavé), and dark (tmavé) lager.

Within those three categories, beers fall on a strength range ranked by degrees on the Balling scale, which measures the concentrated, dissolved solids and sugars in the wort. In America, we might equate this to the Plato scale, which measures the original gravity of a beer.

Lower-alcohol beers around 4% ABV can range from 8°-10° (výčepní), mid-strength beers at around 5% ABV from 11°-12° (ležák), and higher-alcohol beers between 5-9% ABV fall into 13° (silné pivo or speciáls).

So světlé ležák, for example, is a 5% ABV Czech pale lager.

You might be tempted to say, “Wait, what about pilsners!?”

Well, if you’re drinking a pilsner in Czechia, that means only one beer—Pilsner Urquell. In fact, if you walk into a brewery or bar in Czechia that doesn’t serve Pilsner Urquell and say, “Can I have a pilsner?”

They’ll respond, no.

In this country, pilsner is more a brand than a beer style. Any other beers in that style that aren’t Pilsner Urquell are considered pale lagers.

Larkin explains, “You can walk into any bar and say, ‘Can I have your 12° in Czech,’ and the style of beer will be made in the same style as Pilsner Urquell.”

(And if you want to go one step further, the slang for twelve in Czechia is dvanáctka, so when you want to order a 12° Czech pale lager in Czech you would say dám si dvanátcku)

Got it?

Well, maybe if you drink Bus Beer you’ll understand.

Paying Homage to the Czech Pale Lager

Photography courtesy of Peter Kiley | Monday Night Brewing

The 12° Czech pale lager is one of the most popular styles in Czechia.

“That beer was like water over there,” says Kiley. “It’s the first beer you have when you walk into any bar…but it is so much more complex, nuanced, and delicious than what we have as our water of beer in America.”

Cough, cough, Miller Lite. And you call yourself a pilsner. ????

“It is kind of like the holy grail… It’s just one of those beers that, if you saw it, it’s just another beer but once you understand it and grow to love and appreciate it, it’s so far from just another beer,” says Kiley.

And as a brewer, that’s a challenge, brewing a style with nothing to hide behind, such as massive hopping rates, crazy esters, or out-there adjuncts. “It is such an honest and humbling style of beer production that forces you to demonstrate and to practice your acumen,” says Kiley.

It’s one of the most exciting prospects of Bus Beer for Murphy. “The opportunity to use Czech ingredients that have spoken to a bunch of different Czech brewers and try to represent them authentically to an American market and make them love them the same way they do in Czechia,” he says.

And that requires some extensive planning, passion, education, and experience. Namely, a ridiculously long email thread debating minute details (the thread had forty-three responses when I talked to Kiley in February right before they brewed the beer). “It looked like a scene from Russell Crow in a Beautiful Mind where he’s just writing on the wall,” laughs Kiley. “It’s just cool s**t to watch the passion.”

Like debating where the final IBU should land, arguing between thirty-two and thirty-three. “People presented their case,” says Kiley. “In a group like this, no one is allowed to come with the feeling fact. You need to come correct.”

(Larkin says they landed on 35 IBU.)

What they could all agree on, though, were the basics.

The Basic Ingredients of a Czech Pale Lager

Hop selection for Bus Beer | Photography courtesy of Shawn Bainbridge | Halfway Crooks Beer

To start, a Czech pale lager needs soft water (so the group didn’t add any brewing salts or yeast nutrients in Bus Beer) and a floor-malted pilsner-style malt (more on why below ????????????).

Typically, this 12° Czech pale lager also includes a small percentage (three to six percent of the grist) of Caramalt or Munich to help achieve a color of 3.5-6 on the SRM scale.

In Bus Beer, the group landed on a grist bill with almost exclusively imported Moravian Czech floor-malted pilsner malt along with a smidge (six percent) of Caramalt, resulting in a final beer that hit 5.6-6 SRM.

For hops, světlé ležák should only include Czech-grown Saaz, which Bus Beer replicates all the way through, including some whole-leaf Saaz at the end.

“With these beer styles and in Czech beer culture, there is nothing that’s not hyper-intentional, and if we’re going to be presenting through our lens in a place that is not Czechia, you need to come correct,” says Kiley. “We’re not providing ourselves any grace. We really want to be as large of a collective of perfectionists as we can.”

Which means following a few other traditional Czech brewing processes.

Paying Homage to Czech Brewing Traditions

Photography courtesy of Peter Kiley | Monday Night Brewing

Brewing beer in Czechia is very different from, say, in Germany or America.

In fact, when Larkin first visited Prague, he remembered tasting the beer and thinking, “Anything I’ve had in the U.S. that has been called Czech pilsner doesn’t taste like this. Why?”

Johnson had a similar, if not more hyperbolic, reaction. “I remember that first night on the bus having a crisis,” he recalls. “F**k, I don’t know anything. I couldn’t sleep because none of this s**t tasted like what I’d been making. What have I been doing!?”

In reality, Johnson probably should have asked himself, ‘What haven’t I been doing?”

For instance…

Decoction

In Czechia, brewers are also their own maltsters. In fact, the word in Czech for brewer sládek also translates to maltster, referencing how a Czech brewer also floor malts their own barley on-site for their beer.

The process includes drying malt on beds on the floor around a foot to a foot-and-a-half tall at the most.

The temperature range inside these floor beds can vary, leading to under-modified malt whose starches are harder to convert during brewing.

Hence why Czech brewers love decoction.

“I don’t know why or what equipment or knowledge they were missing, but the malt was under-modified and had to be finished in the brewhouse,” says Larkin. Otherwise, if the malts weren’t modified to the right point, brewers would need to use more, which would cost more money.

To finish modifying the malts, Czech brewers decocted, drawing off a set volume of malt (roughly a third) from the mash, boiling the cracked grains anywhere from fifteen to twenty minutes to cause a Maillard reaction or caramelization in the malts (“the same thing that browns your toast or sears your steak,” says Larkin), and moving it back to the main mash.

Brewers then take that whole mash up a temperature step and rest. Depending on the recipe, brewers can take the beer through one, two, or even three decoctions.

Back in the day, temperature control didn’t exist, so decoction roughly approximated how to finish these under-modified malts.

Today, although brewers have the equipment to appropriately get malt to where they need it, the Czechs continue to brew the way they’ve been doing it for thousands of years. It’s not just out of stubbornness either; decoction also adds flavor and texture to the beer.

“[Decoction] provides this depth of grain intensity, flavor, and mouthfeel that I don’t think is replicable,” says Larkin.

For that reason, Bus Beer includes a triple decoction.

“I don’t think it’s the single most impactful step on Czech lager production, but lager production to me is a series of small steps you make to change the final production, and decoction is a big one of those,” says Larkin.

Diacetyl is another big one.

Photography courtesy of Peter Kiley | Monday Night Brewing

To Diacetyl or Not to Diacetyl

A common byproduct of fermentation, diacetyl in America is often described as one of those off-flavors (like buttered popcorn) in beer.

“The presence of diacetyl doesn’t exist in U.S. beer production—we stamp that out and deem it unacceptable,” says Larkin.

Not in Czechia.

Diacetyl is often revered in Czech lagers.

With ales, yeast reabsorbs diacetyl faster because of warmer fermentation temperatures, but because lagers ferment at cooler temperatures, not all of the diacetyl will be reabsorbed.

For that reason, American brewers include a diacetyl rest during lager brewing, raising the temperature at the end of fermentation to ensure the yeast properly reabsorbs that diacetyl and prevents those “off flavors.”

Historically, in Czechia, without temperature control, lagers fermenting in cold cellars wouldn’t rise to the temperature needed to clear all the diacetyl.

So drinkers accepted the flavor in Czech lagers.

“I came back and was like, ‘Yo, I like diacetyl!’” Kiley exclaims.

Johnson laughs, “Yeah, by the eighth beer, it’s f**king great!”

But not everyone will have that reaction, especially if they haven’t drunk beer in Czechia.

“How do we honor it without dishonoring it?” says Kiley. “But also without dishonoring our consumers…who won’t understand that?”

A point of much discussion amongst the group, Bus Beer will not intentionally or unintentionally include diacetyl. “All of us are certainly hesitant to produce a beer with a diacetyl,” says Larkin. “Even the ones that prefer it, we don’t want it to be a screaming amount, to knock you over with diacetyl.”

Johnson says they’re just going to follow the traditional processes and steps, and if diacetyl shows up, so be it, but if not, they won’t force it. Johnson expects the flavor profile to be fairly clean, “but if there is a little diacetyl, we’re not afraid of it… But there is no intervention to create extra diacetyl by any means.”

What Is It Like to Drink Beer in Czechia?

Photography courtesy of Peter Kiley | Monday Night Brewing

A very proud drinking culture, Czechs tend to favor one specific beer producer and a few certain bars.

“There are crazy amounts of beer consumed in this tiny country; it’s not a big place, and there are not a lot of people there, but they love Pilsner Urquell,” says Larkin. “If you’re over forty-five, you’ve probably been drinking the same beer for the last thirty years.”

Quite a different approach from the what’s-the-latest-release-that’s-here-today-gone-tomorrow approach in America.

“What I realized was people don’t have a beer; they have a bar,” says Johnson. “They don’t look at it like this is my favorite beer; they look at it like this is my favorite bar.”

Kiley chimes in, “Or my favorite tapster.”

See, in Czechia, drinking isn’t just about the beer. It’s also about the person that poured you that beer—called a tapster.

Each tapster has their approach—their own way of pouring, presenting, and serving that beer to you.

And it all matters.

“You go to Czechia, and they say, ‘The brewer makes the beer, the tapster makes the experience,’” says Johnson.

Something all six discovered during their travels.

“We would drink a beer, go across the street, drink [the same beer], and it would taste completely different,” says Johnson, who had only tried Czech styles made by U.S. producers before the trip. “That blew my mind…but you started to realize that Czech beer isn’t always about the beers; it’s more than that. It’s about the experience—where you are, who you’re with, how it’s poured, who’s serving it, and who you are in that moment.”

So much so that, if something goes wrong with the beer, guess who gets blamed? The tapster.

“They won’t say this Pilsner Urquell sucks; they’ll say these guys don’t know how to pour Pilsner Urquell,” says Johnson. “Here, you go to a bar, drink any of our beers, and hate it, you blame us. You don’t blame the place, you don’t blame their line cleaning, you don’t blame the transit, you don’t blame the wholesaler, you blame the brewer. The brewer f**ked it up.”

For the Czechs, the tapster is a position as respected as the brewer. If not more.

“There is a lot of pride in what they do,” says Bainbridge. “It’s a career.”

Whereas, in America, we often view bartending or serving as a short-term position, a pitstop on the way to a “real” full-time job, the Czechs consider the tapster a serious, well-respected career.

But how do you replicate that idea in the United States?

Tallboys, Tall Orders, and Standing Tall

Photography courtesy of Peter Kiley | Monday Night Brewing

It’s 8 o’clock in the morning for me on the West Coast. I’m Zooming in with all six guys together again for the first time since their Czech Republic trip to brew Bus Beer at Green Bench Brewing in St. Petersburg, FL.

“Being together feels like no time has passed,” says Johnson. “You build a weird connection when you spend that much time on a bus drinking for that long in so many places with people. You get to know and care about each other and realize how many people care about the same things.”

Bainbridge adds, “It’s almost like a class reunion.”

“We went to beer camp!” exclaims Kiley.

I could feel the camaraderie through the computer. All six pinged and ponged off each other, laughing as they reminisced about Johnson singing karaoke on the bus (apparently, he has the pipes of an angel. Kiley’s words, not mine).

Connecting as Johnson, who is Black, recalled an instance of prejudice he ran into at one of the local Czech bars where someone used a racial slur.

Earlier in the day, they all had chatted on the bus about what to do if that happens.

“Lo and behold, we’re in that situation later that night,” says Johnson.

Peterson asked the guy to watch his mouth only to have him respond, “What do you mean?” and repeat the word.

Peterson again asked him to stop. Only to have him say it’s just a word, it doesn’t matter, it doesn’t mean anything. They went back and forth without making any headway.

Eventually, Johnson just stood up and left.

“These dudes stood up right after me and walked out with me,” he says, recalling that as soon as the situation escalated, Murphy actually asked for and paid the bill. “We leave, and I’m down the street when Ben walks up to me and grabs me, and then the whole crew comes up and grabs me. It was this moment of we all had each other.”

Perhaps ironically, Johnson used this story to illustrate how Czech beer is more than a product. Drinking in Czechia centers around the experiences you have together as humans.

“Guess what?” says Johnson. “That was the worst f**king beer I had that whole trip.”

The Wheels on the Bus (Beer) Go Round and Round

Photography courtesy of Peter Kiley | Monday Night Brewing

For the group, brewing Bus Beer has been an opportunity to be together again and to bring together everything they learned.

“I want to inspire people about the purest things around craft beer—exploration, adventure, friendship, connectivity,” says Kiley, who felt invigorated after the trip, claiming no beer trip could ever top this. “This beer is the distillation of all my favorite things that make craft beer unique as an industry. It’s unlike anything else, and this beer pays testament to that.”

Bus Beer celebrates all those moments—when they laughed, learned, and laughed some more. When they experienced the collective trauma of drinking Pilsner Urquell at 8am. And when they had each other’s back and stood tall together.

And Bus Beer?

Well, hopefully, it’ll be the best f**king Czech pale lager Johnson or anyone drinks in America.