Shop

Oyster Stout! Oyster Stout! Oyster Stout!

"But the pearls were accidents, and the finding of one was luck" - John Steinbeck

Nothing compliments a Maine summer’s day more than a helping of oysters on the half shell: briny and refreshing, a spiritual connection between you and the ocean. And nothing takes the chill out of an icy winter’s eve better than a stout: heartening and robust, a tall, dark glass of roastiness best enjoyed by a nicely crackling fire but worth drinking without the bonus atmospheric touch. Imagining the setting and circumstances where you’d want to experience these two things together is a puzzle, and that puts the oyster stout, where mollusks and crystal extra dark malt meet, in an exceptionally niche space.

Not all foods and beverages pair well together; for every “tomato and mozzarella,” there’s a “pineapple and pizza.” If the mere mention of this substyle sends your taste buds into revolt, you’re probably not the only one.

Precious few breweries make oyster stouts today. But because it takes all kinds, people exist who enjoy them. More critical than who drinks oyster stouts is why they’re brewed in the first place, along with how.

While We’re At It: When Did Oyster Stouts Become a Thing?

Photography courtesy of Steven Woodburn | Hospitality Magazine

Like many brewing advancements, the oyster stout’s roots trace back to the late 1800s and early 1900s England, with an origin story as suspect as an outdoor raw bar in August. Pubs served oysters as bar snacks to thirsty stout hounds.

Somewhere along the line, brewers had the idea to use crushed shells as clarifying agents; somewhere along that line, the shells wound up in the boil, and the meat followed shortly thereafter.

Although more or less true, the exact dates and progress of oysters in beer are uncertain.

Oysters were a public house staple at the turn of the nineteenth century; stout was the dominant beer style. If you don’t believe gossip, believe Guinness.

England pioneered the concept, but New Zealanders gambled on the oyster stout’s viability in 1939, and eighty-four years later, here we are: in an oyster stout drought.

Granted, the variation was never popular. Not everyone likes oysters. Not everyone likes stouts. Putting them in the same package inevitably attracts only a specific set of beer connoisseurs. Suited to few palates, though the style may be, the oyster stout’s near disappearance from craft beer’s radar feels like a historic loss.

The World Actually Isn’t Your Oyster Stout

Photography courtesy of John A. Paradiso | Schlafly Stout and Oyster Festival 2018

Of course, there’s a reason for that scarcity—actually, several.

Like any ingredient specific to a recipe or style, oysters have criteria to meet for brewing purposes, and brewers are frankly better off not troubling themselves if they can’t meet them, starting with transportation.

From Sea to Shining Sea

If you want New Zealand hops, you call NZ Hops Ltd. If you want Georgia peaches, you call Harry & David. If you want Maine oysters, you have limited options, especially if you live in the middle of the country.

A fun fact about oysters: They don’t travel well.

“Once they’re outta the ocean, how are you gonna store them?” says Tyler Fitzpatrick, the brewmaster for Cambridge, MA’s Lamplighter Brewing Co. It’s a simple question that only a few breweries can effectively answer. “You can’t freeze them,” he says. “They’re only gonna last in cold storage for a certain amount of time.

For a brewery in, say, the Northeast or along the West or Gulf Coasts, figuring out how to bring the oysters to the brewhouse is easy. That’s the benefit of being within driving distance of the ocean. For breweries further from the Pacific or Atlantic Ocean, the logistics become trickier for every extra hour it takes for the oysters to make it through their doors.

“You gotta have a source of oysters,” agrees Stephen Demczuk, founder of the Edgar Allen Poe-themed RavenBeer in Baltimore, MD, which entered a licensing deal with Oliver Brewing Co. in 2021 to continue brewing and distributing its beers, becoming Baltimore-Washington Beer Works. “It’s probably tough to make [oyster stouts] in Kansas or someplace like that. Could be pretty rough.”

Demczuk suggests an alternative. “Maybe in West Virginia, you’d use mountain oysters instead,” he jokes, referring to a certain bull body part often found in dishes in the Rocky Mountain region.

Maintaining the Best Bivalves

To understand what “pretty rough” might look like for a landlocked brewery, consider that oysters can still do a number on the tummy even if eaten in spitting distance from the beach.

For emphasis, Demczuk relates a bad oyster experience of his own: “I had raw oysters a few years ago at a restaurant in the Inner Harbor in Baltimore,” he says with a laugh. “I got real sick. They tasted a little funny; I ate ‘em anyway. I should not have.”

Suppose a restaurant with quick access to countless reputable aquaculturists can serve bad oysters. In that case, it stands to reason that a restaurant several states away from the shoreline accepts a greater risk (though, in fairness, using the shells and not the meat curtails that liability).

For perspective, restaurants tend to store unshucked oysters on ice for about a week and change; generally, one should consume oysters within two or three days of purchase.

That date range is more of a cautionary guideline for breweries that don’t have to surmount the hurdle of bringing the oysters to their taproom. For inland breweries, it’s a conundrum not worth solving.

Aw, Shucks

Photography courtesy of John A. Paradiso | Schlafly Stout and Oyster Festival 2018

If you’ve ever watched a mise en place relay race on Top Chef, or, god forbid, if you’ve ever tried shucking oysters with your own hands (plus a knife and some bandages), then you’re aware of the time and fuss prepping oysters requires.

Nobody likes acknowledging this terrible truth of running a business, and nobody likes contextualizing breweries as “businesses” instead of “happy places,” but brewing beer takes time, time is money, and the opportunity cost incurred by readying oysters for the brew day is meaningful.

“The one time we did do an oyster stout, we shucked all the oysters, we had a little party, and ate ’em all while we were brewing the beer,” Fitzpatrick recalls with a chuckle. He and the Lamplighter team did the literal dirty work, scrubbing the shells free of algae and sludge and collecting the shells in a bucket to catch whatever brine water remained inside. The meat was their reward, alongside team-building fun.

But breweries don’t hire people to do a prep cook’s job. They hire people to brew beer. Brewing beer occasionally means wrangling ingredients outside standard beer recipe parameters, yes, but everyone knows how to peel oranges, hull strawberries, or skin cucumbers. Not everyone knows how to shuck oysters; even when they do, it’s still a tedious pain in the ass.

“Even brewing an oyster stout on our production system, a 20-bbl batch, you’re shucking a lot of oysters, and that’s time consuming,” says Fitzpatrick. “You can have a good time doing it, but if that’s one of your flagship beers, what are you doing?”

There are shortcuts around everything in the world of food and beverage. For example, Fitzpatrick cites fenugreek as an intelligent way of brewing maple flavor into beer without the cost of real maple syrup, which, frankly, ferments out anyway. Maybe someone has an oyster shell equivalent of that hiding away in their cabinet, abiding by the logic of “fake it ‘til you make it,” but it doesn’t seem that one exists yet. Whatever the case, Fitzpatrick advocates the “drink local” approach when ordering an oyster stout.

He explains, “If you’re gonna consume or look for an oyster stout, I would definitely look at your neighborhood brewery that’s not a 50-bbl brewhouse system … because you know they use the oysters, and they put the time into it.”

Pearls of Wisdom, Bushels of C-Notes

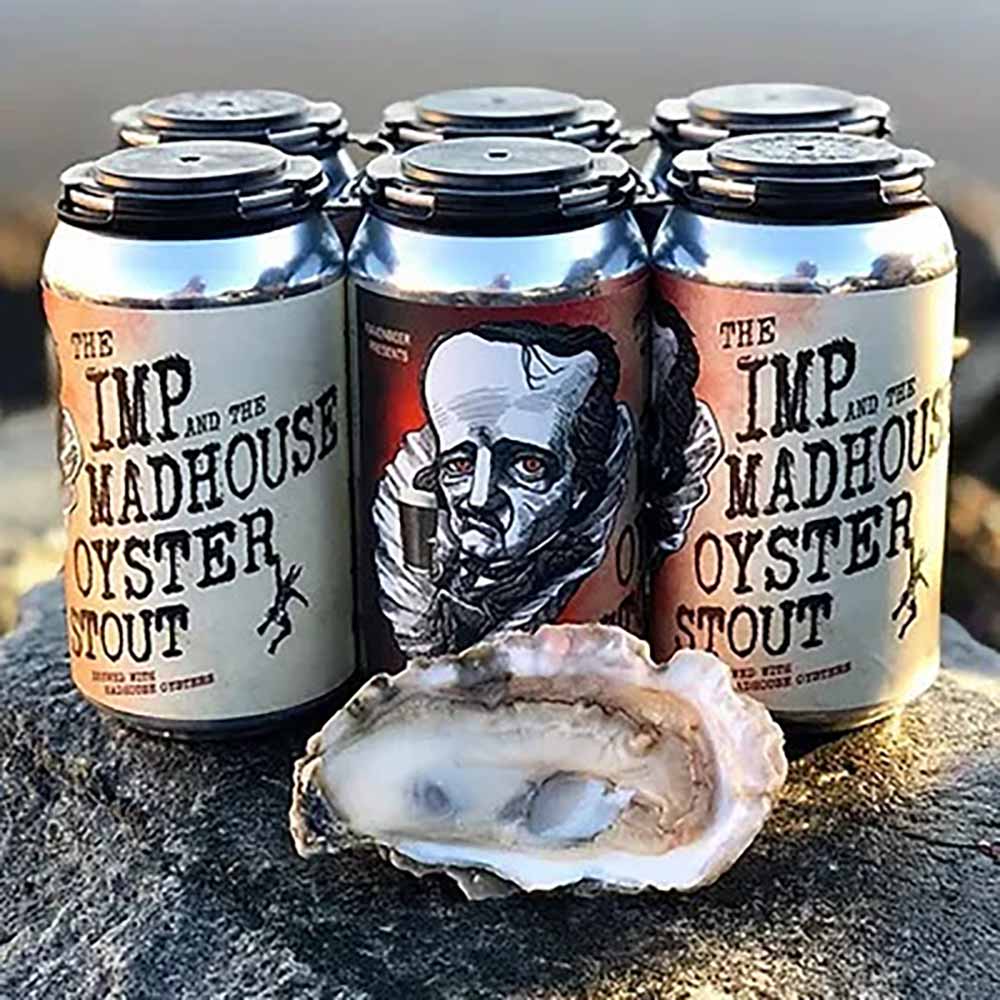

Photography courtesy of RavenBeer

If a brewery can make up the time and safely source their oysters, all that’s left is cost.

A bushel of oysters (~100-150 shells) runs anywhere between $60 and $250, depending on where you’re buying them. This is only reasonable if you plan on brewing one barrel of stout, which would, of course, be unreasonable.

When RavenBeer made their oyster stout, The Imp and the Madhouse—both a nod to Poe and a hat-tip to their supplier, Madhouse Oysters—Demczuk notes they made way more than one barrel.

“We used the whole oyster,” he says. “We roughly used one oyster per gallon. We were doing 60 barrels. So, 60 times 31…that’s a lot of bushels of oysters.”

Don’t worry about the earth shaking under your feet; the shockwaves from beer geeks’ jaws hitting the floor after crunching numbers on their calculator apps. The price tag on this one specialty ingredient for this one specialty beer means, among other things, that oyster stouts are cost prohibitive as well as locationally prohibitive—which means that they have to be worth all of it.

Life Can Be Much Better Under the Oyster Stout Sea

The appellation may gross you out, but the oyster stout’s flavor profile won’t. “It’s like adding salt to your cooking,” Fitzpatrick explains. “It’s boosting the flavor.”

Lamplighter made its oyster stout, Black Pearl, using the shells alone (obviously because the crew ate the meat) for the calcium carbonate comprising their microstructure. Usually, that’s a compound to avoid in beer. In darker beers, though, calcium carbonate offsets the malt’s acidity. “The carbonates help raise your mash pH,” says Fitzpatrick. “The roasted and caramel malts in a typical stout grist bill will drop the mash pH. You want to be on the higher end of the brewer’s range for mash pH when you’re brewing sweeter, more full-bodied beer.”

Hitting that range produces a less fermentable beer, which means more body, clanging against any misconceptions about the oyster stout’s taste.

For the record, it isn’t oysters.

“It’ll be kind of salty,” Demczuk says. “The texture will be smooth, good mouth feel and all that, not bitter in the style of a Guinness, but something closer to a Young’s Chocolate Stout.” That description sounds closer to a chocolate-covered pretzel than a beer-bathed bivalve.

“It’s not like I drink [an oyster stout] and go, ‘Oh yeah, there’re the oysters,’” Fitzpatrick points out. “It’s the salt; it’s the full-bodiedness of the malt.” To him, the oyster stout is a cousin to the milk stout; the comparison shapes his approach to brewing this substyle and should pique your interest.

Knowing where oyster stout comes from might help, especially in light of what Demczuk calls the craft beer industry’s transience. “It changes so often,” he says. “But I think a true craft beer drinker who likes dark beers would definitely try it, and knowing a little history would go after it.”

Hop Culture’s Picks for the Best Oyster Stouts to Try Right Now

Photography courtesy of @henhousebrewing

Oyster Stout – HenHouse Brewing Company

Santa Rosa, CA

HenHouse has been brewing its Oyster Stout with Tomales Bay-bred Hog Island Oyster Co. for over a decade. Considered one of the brewery’s flagship beers (pretty unusual; in fact, can you name another brewery that counts an oyster stout as one of its core beers?), Oyster Stout is the only beer HenHouse has brewed consistently since 2012.

A tribute to the area’s local waterways, HenHouse’s Oyster Stout also includes Sonoma County-grown barley, those Tomales Bay oysters, and San Francisco Bay sea salt.

Talk about terroir! With every sip of its inky blackness, Oyster Stout gives you a taste of Northern California.

Brackish – Fonta Flora Brewery

Morganton, NC

Fonta Flora chose the name for this beer, well, because “brackish” it is indeed—salty verging on mineral. However, this is, of course, a feature. Brackish is an excellent expression of the oyster stouts’ pairing of robust, smooth body, plus subtle hints of sweetness, with savory characteristics. In fact, the brewery leans into the former by blending the beer with North Carolina sea salt, bumping up the salinity, adding extra layers to the flavor profile, and relating the substyle to the depths from which its star ingredient comes.

Black Pearl – Lamplighter Brewing Co.

Cambridge, MA

Conversely, Black Pearl achieves the opposite effect as Brackish—surprising earthiness—while retaining the star ingredient’s abyssal side. Black Pearl is something of a miracle among its cousins in the “oyster stout” category, passing along notes of coffee and dark chocolate; the hits, in other words.

Lamplighter brewed this stand-out, well-balanced oyster stout with the help of Medusa Brewing over in Hudson, MA, and Island Creek Oysters in Duxbury, MA, emphasizing the oyster stout as a product of good terroir as well as smart brewing decisions. Which is also probably why Lamplighter hasn’t brewed any since 2019.

The Imp And the Madhouse – Baltimore-Washington Beer Works (nee RavenBeer)

Baltimore, MD

We’ll let the beer’s Untappd description do the talking here, “Madness takes on many forms. Justifying self-destructive, perverse behavior is in itself mad. Madhouse Oysters has invested years of insane work to cultivate the fruit of the oyster. RavenBeer, guilty of its own perverseness, has taken two decades to develop its beer—sometimes ignoring orders, not conforming, and being a bit devious and mischievous. RavenBeer and Madhouse Oysters are like Poe’s Imp of the Perverse: We know what we do is in itself deranged, but perfection excuses our madness. Oysters brewed in stout? Now, that’s insanely good.”

Entropy – Mountain Culture Beer Co.

Emu Plains, New South Wales, Australia

Now, we don’t live in Australia, so we haven’t tried this beer, but this oyster stout currently ranks as the all-time top-rated oyster stout on Untappd…and it only dropped early this year in May! So that’s pretty high praise.

Entropy includes fresh Tasmanian Pacific oysters from Tasmanian Oyster Co. harvested from Port Stephens, New South Wales, Australia.

Mountain Culture Beer Co. gets the oysters into this beer’s boil only four hours after Tasmanian Oyster Co. pulls them from the water. According to Mountain Culture Beer Co., “Those extra creamy oysters are calcium-rich, which provides a softness and rounds out the roastiness of the dark malt just as they did back in the day when brewing traditional stouts.”