Shop

Brewing for Impact With Fonio: A 5,000-Year-Old Miracle Grain from Western Africa Forging the Future

Hold the fonio.

Hop Culture's Hottest Stories:

It all began with a chance meeting at Questlove’s house.

“That’s a line you can’t make up,” thirty-year Brooklyn Brewmaster Garrett Oliver tells me with a laugh while we’re chatting over Zoom.

About five years ago, while on the Brooklyn’s Museum of Food and Drink board, Oliver participated in a fundraiser at Questlove’s place.

While there, he met Pierre Thiam, chef, and founder of Yolélé, a company focused on one particular centuries-old African grain.

One that requires no fertilizer, no pesticide, no irrigation, and no chemical inputs. A grain wholly reliable and resistant to climate change of which farmers could grow two crops annually at the edge of a desert where it only rained three times a year.

A grain called fonio.

Afterward, Oliver says he asked himself, “I wonder what beer this grain would make?”

What Is Fonio?

Fonio existed way before Oliver ever asked himself that question in Questlove’s house.

Way, way before, actually.

“Fonio is a grain that has been cultivated in West Africa for thousands of years,” Thiam wrote to Hop Culture in an email. “It could be the oldest cultivated grain in Africa.

The Senegalese chef who moved to the U.S. to work in New York City restaurants first encountered fonio while traveling to different Senegal regions doing research for a cookbook.

After years of working in restaurants and living in a food-rich city mysteriously missing African cuisine, Thiam hungered to do something more meaningful.

“I wanted to give back to [New York], the city that allowed me to follow my calling, and to my origins and ancestors in Senegal,” Thiam said during a TED Talk. “I wanted to contribute to a universal civilization but didn’t know how to make an impact as a cook and writer.”

While visiting the remote Southeast region of Kédougou in Senegal, he discovered a 5,000-year-old grain that had almost completely disappeared from Senegalese culture: fonio.

Once widespread, fonio, which Thiam says archaeologists have even found inside ancient Egyptian pyramid burial grounds, has shrunk significantly.

Thiam cites several reasons.

First, colonization instituted a system promoting the cultivation of cash crops like peanuts, cocoa, and coffee as opposed to local grains like fonio. Additionally, colonists preferred to import foreign grains such as wheat, maize, and broken rice, driving competition that replaced fonio. Lastly, according to Thiam, fonio is very hard to process and requires manual labor to turn it into food.

For all these reasons, fonio production almost died out. Today, the grain is mainly found in the Western part of the Sahel region, from Senegal to Mali, Burkina Faso, and Nigeria.

Which is still crazy because fonio is something of a miracle grain.

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

Why Is Fonio a Miracle Grain?

In his TED Talk, Thiam explains that the Dogon, a great culture in Mali, called it “po” or “the seed of the universe.”

“In that ancient culture’s mythology, the entire universe sprouted from a seed of fonio,” says Thiam.

Fonio has practical applications, too. “It is called a ‘miracle grain’ because of its resiliency,” writes Thiam. “It can mature within two months, so farmers know that they can rely on fonio when other crops fail to grow, which is why it’s also nicknamed ‘hungry rice.’”

He continues, “It can thrive in dry and arid areas like the Sahel region of Africa (south of the Sahara desert). It requires very little irrigation to grow and no chemical inputs. Lastly, it restores the soil thanks to its deep roots, which helps to mitigate the advance of the desert.”

It’s also packed with nutritional amino acids not found in other major grains, such as barley, rice, and wheat.

“Fonio is gluten-free and a nutrition powerhouse,” wrote Thiam. “It is quite versatile and can cook in five minutes.”

In Kédougou, fonio even has the nickname “ñamu buur,” which means “food for royalty,” and it’s served to guests of honor.

When Thiam visited, “We were served a delicious fonio dish,” he wrote. “We were told that, in their tradition, to serve fonio is their way to honor guests. They call it the grain for royalty because of its delicate texture.”

Yet in the West, incredible local grains like fonio are often considered substandard. And when they are prized (read: quinoa quagmire), they’re frequently co-opted and industrialized.

For Thiam, he asked himself, “How can we turn fonio’s current status of ‘country-people food’ into a world-class crop?”

Founded in 2017, his company Yolélé (a Fulani term roughly translating to “Let the Good Times Roll” in English) shares African ingredients like fonio with the entire world.

Yolélé creates products like plain fonio, fonio pilafs inspired by West African flavors, fonio flour, and even fonio chips. By supporting small rural West African farmers, Yolélé also brings economic opportunities to the communities of the West African Sahel.

But while Thiam has brought West Africa’s oldest cereal grain to the shelves of stores like Whole Foods and Target, he never thought about what type of beer fonio could make.

Enter Garrett Oliver.

What Is Brewing for Impact?

Photography courtesy of Brooklyn Brewery

Recently, celebrating his thirtieth year as Brooklyn Brewery brewmaster, Oliver found himself at a crossroads that was not unlike Thiam’s several years ago.

For over three decades, the James Beard Award-winning brewmaster has changed the shape of the industry, breaking barriers and starting initiatives like The Michael James Jackson Foundation for Brewing & Distilling.

How could Oliver celebrate his belief in beer’s power to unite people, cultures, and traditions while leaving a lasting legacy with a tangible impact on the future?

Rolling out through 2024, Brewing for Impact brings together a coalition of brewing partners around the world—Maison Kalao from Senegal, Thornbridge in the U.K., Omnipollo in Sweden, Carlsberg in Denmark, Russian River in California, Jing-A in China, Guinness in Ireland, and, of course, Brooklyn Brewery in New York—to brew a series of collaboration beers with the versatile, climate-resistant West African fonio.

Oliver doesn’t quite know how to put it, but he says with Brewing for Impact, “I’m connecting all the pieces of me together in this project as a brewer [and] as an African American.”

Photography courtesy of Brooklyn Brewery

According to Oliver, it was essential for him to engage in a project that showed the common misconceptions about the history of beer.

“If you look at the way we approach brewing in the United States and the West, the folks that we always think of as the progenitor of our great brewing culture are folks like this,” says Oliver, pointing to a sign of a Victorian-era British beer called Joule’s Stone Ale and Royal Stout over his left shoulder before switching to his right shoulder to show the artwork of an African woman. “In fact, it’s her.”

Oliver explains that beer brewing in sub-Saharan Africa, along with Sumeria and parts of China as well, probably dates back beyond 2500 BC. “Americans and other Western societies tend to [think of] beer as ‘European,’ [but] this, if nothing else, is simply historically false,” says Oliver. “It’s the beer equivalent of claiming that Elvis Presley invented rock and roll. But to this day, the vast majority of Americans think Elvis wrote ‘Hound Dog’ and have never heard of Willa Mae Thornton; this is galling, to say the least—no less in beer than in other areas of culture.”

Candidly, he says there’s a reason his Zoom background includes representations of both English and African cultures.

“Of course, as Westerners, we largely brew in Western styles and with Western ingredients. There’s nothing wrong with that, and I obviously love traditional European beers,” he says. “But we are missing out on other flavors and, in the case of fonio, excellent brewing grains that can be used to bring bright new flavors and deeper sustainability to our beer culture.”

He continues, “I think that fonio is the best one I’ve ever seen.”

Bringing Fonio to Beer

Photography courtesy of Brooklyn Brewery

After a chance meeting with Thiam at Questlove’s house, Oliver started exploring how to brew with fonio, making a one-hectoliter batch at Brooklyn Brewery.

“Lo and behold, there were all these beautiful flavors,” he remembers. “Everybody’s tasting this beer, and we’re like, wow, this is great. It smells like white wine, lychee, and tropical fruits.”

Usually, with alternative grains like spelt and sorghum, Oliver explains that you get descriptors like nutty and earthy, “all these other things you try to pretend you want … and the dirty, little secret is that we don’t always love these,” he says.

But fonio immediately became what Oliver called a “game changer” because of its flavor.

In 2019, at the Great American Beer Festival, Brooklyn Brewery debuted its first fonio beer, Teranga, brewed with a malt bill that included fifty percent West African grain.

“Brewers were telling other brewers to come to taste the beer,” Oliver recalls, smiling.

Beer became a vehicle to educate people about fonio and to make an impact.

Brewing for Impact Ticking Every Box

Photography courtesy of Brooklyn Brewery

The beauty of brewing with fonio mimics creating one of Yolélé’s products.

“Brewing with fonio opens a path of development for the small farmers’ community who have no access to the market for their grain,” wrote Thiam. “Contracting farmers to grow more fonio opens economic opportunities and addresses the challenges of food security and climate change. It has a triple impact on the community and makes a delicious beer, so there is also a positive impact on the consumers.”

You’re not only making a delicious product but paying African farmers a fair price, supporting rural families, and creating economic opportunities in markets historically manipulated by colonizing communities.

“We in the West generally come and take things,” Oliver explains. “Here’s an opportunity to give something back to these communities. … On every level, culture, social justice, environment, flavor, and ease of use, fonio basically ticks every box.”

Oliver believes Brewing for Impact is also “a great way to tie ourselves into communities of color as brewers across the United States.”

Community is the word that Oliver keeps coming back to because, for him, that’s the ultimate deliverable of this collaborative project.

“The first thing people ask me is, ‘Can you grow this in the United States?’” says Oliver. “That’s the wrong question. Community is the deliverable of the project. We are paying these people where they are to do what they’re doing. The question is not ‘Can you take this?’ But ‘Can you pay these people for it and then use it for your own benefit and their benefit at the same time?’”

It’s why Oliver knew he couldn’t do this alone just at Brooklyn Brewery. He needed to bring in other impactful breweries from across the world.

Those like Maison Kalao, Thornbridge, Omnipollo, Carlsberg, Russian River, Jing-A, and Guinness.

“We’re just priming a pump,” he says. “Those are the people who are actually going to move the needle.”

Garrett Oliver at Omnipollo | Image courtesy of Brooklyn Brewery

Every month from April to November, a different brewery will release a new fonio beer, including:*

April – Maison Kalao (Senegal): The Brooklyn A Dakar Pilsner, coming in April, is the latest from a newer lineage of fonio beers at Maison Kalao, initiated after witnessing Oliver’s innovative use of the grain grown in their own country.

May – Thornbridge (U.K.): Launching in May, Thornbridge Brewery introduces the world’s first Pale Ale – Cask Beer made with fonio. This blend of tradition and innovation celebrates a fifteen-year friendship rooted in Oliver’s admiration for British cask ale, the tradition that sparked his brewing career.

June – Omnipollo (Sweden): Omnipollo’s Blacker Chocolate Stout, set for release in June, reimagines the first beer Oliver ever brewed for Brooklyn Brewery – Black Chocolate Stout – with a focus on fonio’s sustainability.

July – Carlsberg Laboratory (Denmark): The launch of a 100% fonio beer in July is a collaboration with Carlsberg Research Lab, showcasing both Carlsberg’s and Garrett’s enthusiasm for pioneering sustainable brewing practices and exploring fonio’s potential in new frontiers of beer.

August – Russian River (U.S.): Russian River’s Belgian blonde beer with fonio, launching in August, emerges from the deep friendship between Garrett and the owners of Russian River, Vinnie and Natalie Cilurzo, and their shared commitment to excellence coupled with a desire to explore being more sustainable in brewing.

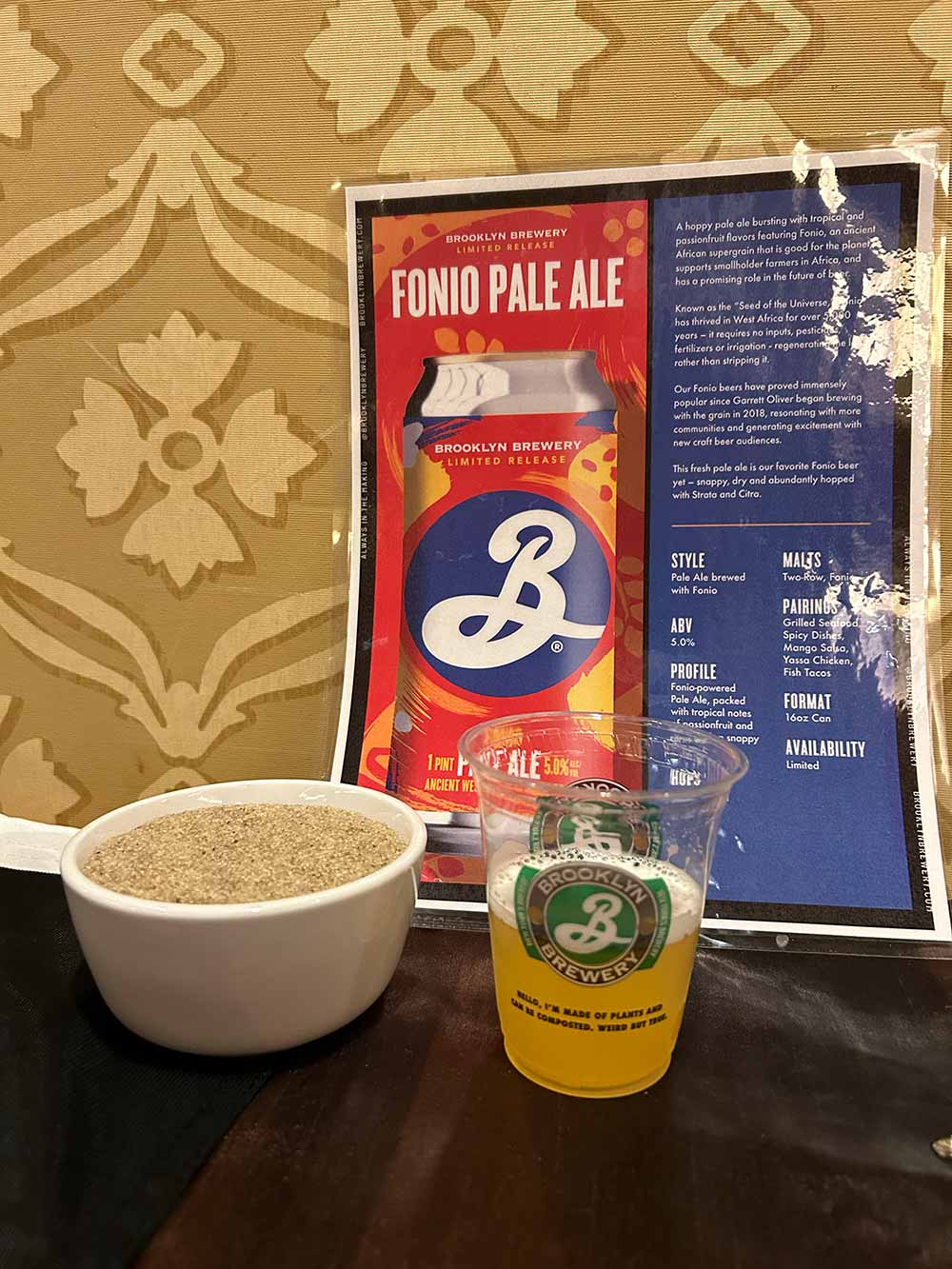

September – Brooklyn Brewery (U.S.): In September, Brooklyn Brewery adds to its impressive fonio beer lineup with a new pale ale brewed with fonio, embodying the Brewing for Impact ethos and Oliver’s continued innovation with the grain.

October – Jing-A (China): Releasing in October, the West Coast IPA made with fonio underscores a unique connection between Oliver and Jing-A—who first introduced Garrett to Beijing’s brewing culture—while exploring the historical significance of native grains like fonio.

November – Guinness (Ireland): Guinness’ Fonio Extra Stout, launching in November, highlights Garrett’s long-time adoration and respect for the iconic brand—which has deep roots in Africa and around the world—and reflects his personal ties to Ireland—both major sources of inspiration throughout his brewing career.

*Editor’s Note: Information provided by a press release sent to Hop Culture from Brooklyn Brewery.

Those brewers involved with the project have already said tremendous things.

During a presentation at the Craft Brewers Conference this year in Las Vegas, NV, Russian River Brewing Company Co-Founder Vinnie Cilurzo talked about its versatility and flavor.

“I had never heard of this grain until Garrett brought it to our attention, but it is the easiest to brew with,” he commented. “Absolutely beautiful flavor in the beer.”

Oliver also told me. “I know the Guinness guys brewed their first test batch and were all giggly about it.”

He continues. “It’d be one thing if the grain didn’t taste great or was hard to use, but it actually is awesome. Everybody that has brewed with it so far is like, ‘I can’t believe I didn’t know about this.’”

What’s Next for This Miracle Grain in Beer?

Photography courtesy of Brooklyn Brewery

Oliver hopes that Brewing for Impact is just the start. Within two to three years, he wants to see some of the biggest breweries start brewing with fonio. Even if it’s just a fraction, say five percent, of their beers.

“I always knew that real impact would come once fonio is used as an ingredient in larger industries,” wrote Thiam. “Brewing for Impact is a concrete way of leading the path. I hope that it will incite other large industries to join the movement.”

In the craft community, Oliver says that fonio should become just another ingredient in a brewer’s recipe book. One that you can use as readily as two-row or pilsner malt.

While on a cultural level, Oliver would like to see fonio reach the status of quinoa while remaining an indigenous grain supporting local farmers and West African communities.

“I hope that the future of the brewery industry includes bringing sustainable development to Africa, a continent with an ancient beer-making tradition,” wrote Thiam. “It would be poetic justice.”