Shop

Inside the Cellars: Discovering the Budějovický Budvar Hidden Fresh-Hop Beers

????

Looking for More From Czechia?

Editor’s Note: This is the fourth in a series of articles created in collaboration with the Czech Ministry of Agriculture that invited Hop Culture to join a group of American and Canadian brewers on a trade mission trip to the country to learn more about Czech brewing and ingredients.

Our Favorite Breweries and Bars to Visit in Czechia

Pivovar Proud: The Electrifying, Experimental Brewery at Pilsner Urquell

Kazbek: Everything You Need to Know About This Surprising Czech Hop

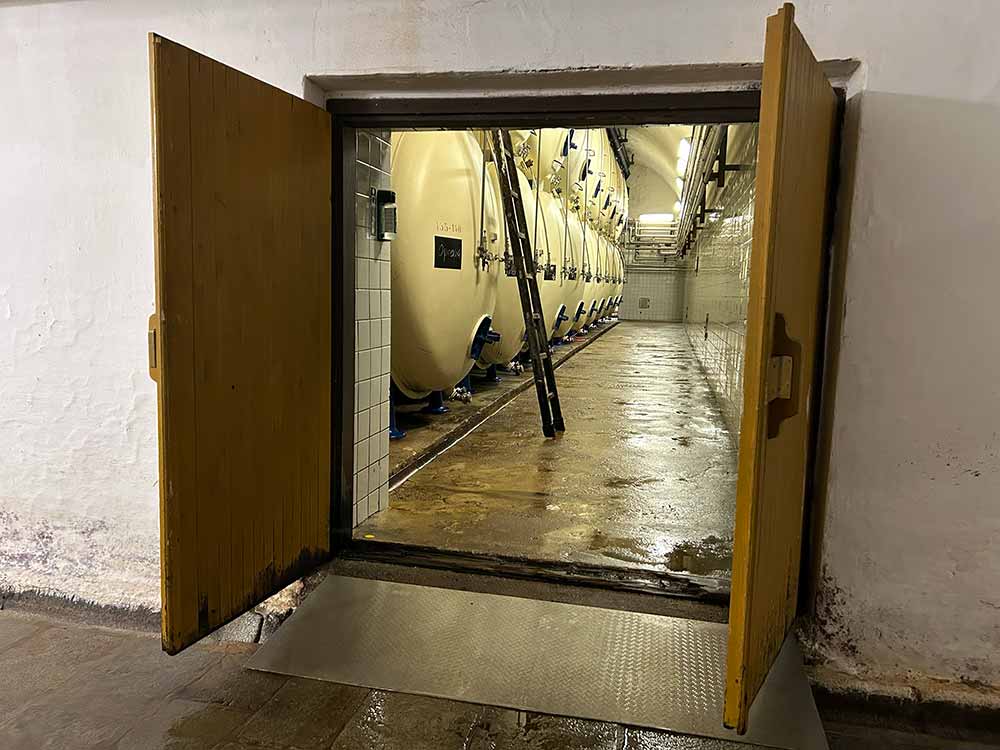

The tan doors stood slightly ajar. Inside, a concrete floor slick with puddles of perspiration and white tiled walls reflected huge cream-colored tanks stacked like chips in a Connect Four board. A lonely ladder perched on the top row seemed to lead to nothing. But this nondescript room in the damp cellars of Budějovický Budvar (making arguably the original Budweiser) was everything. Tucked away in the back corner, two tanks stood resolute, silent to the secret they carried in their burgeoning bellies.

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

As our group walked by, curiously peeking our heads inside, Adam Brož, Budvar’s tenth brewmaster, teased us. In almost a whisper, he said, “We will have time enough to be in this room because [the tanks in there] are the secret.”

Dressed in a neon yellow jacket with black stripes, grey dress pants, and a paisley cream shirt underneath, Brož seemed to smile every time he talked, so it was hard to tell if he was serious.

Turns out he was right. In that room, we found a secret worth the wait.

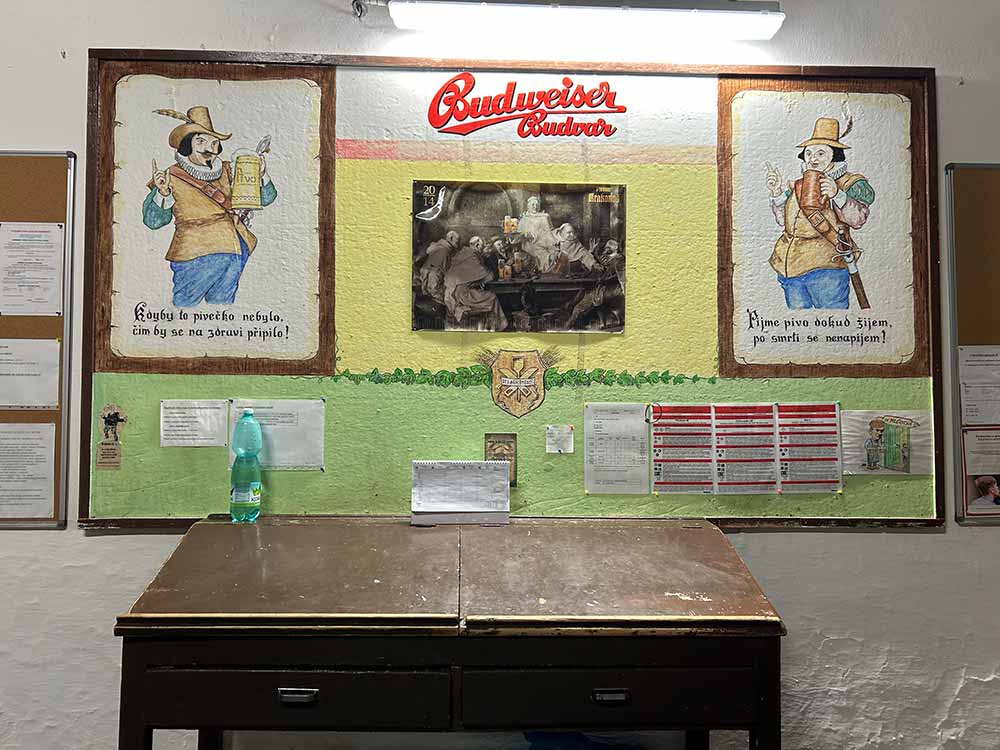

A Very Short History of Making Lager at Budvar

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

The southern Bohemian town of České Budějovice, otherwise known as Budweis (its German name), has a rich beermaking history, much like Plzeň, about 150 km to the northwest.

Since October 1895, a Czech joint-stock brewery (now known as Budějovický Budvar) has produced Budweiser, the generic name given to Budweis beers.

For almost one hundred thirty years, the brewery has adhered to its own process for making its version of an original premium lager—Budweiser Budvar.

When Brož greets our group of twenty American and Canadian brewers on a five-day mission trip to Czechia, he immediately makes this clear. “I am the tenth brewmaster in the [brewery’s] history, approximately 130 years. It means that the average age of all the brewmasters is thirteen years. My [time] at the position is fifteen years, so I’m above the average,” he explained with a laugh. “Why am I saying this? [Because] that’s the guarantee of continuity of this brewery since beginning in 1895 when a very unique recipe was developed, and we’ve been operating with this unique historical recipe of lager still today.”

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

As Brož ushers us into a sparkling brewhouse full of copper kettles, he explains the legendary process.

Making Budweiser Budvar starts with soft water from a natural lake beneath the brewery, accessed via a thousands-year-old well and a lower-modified Moravian Haná malt, a two-row Czech barley.

Brož takes the wort through a double decoction, which he spends extra time detailing to us. A crucial part of making Budweiser Budvar, the decoction starts at 37° C before heating the mash to 50° C. At this point, Brož pumps a third of the volume into a separate kettle, heated to 65° and up to 75° C; he repeats the process a second time.

“It took me four minutes [to explain to you] now, but in reality, it takes four hours!” Brož exclaims, noting that the extra step “creates beer we want, and we won’t change in the future.”

For hopping, Brož uses only the “fine Zasr (Saaz) hops” in the form of pressed cones. He doses three times, a signature of Budějovický Budvar.

From there, Budweiser Budvar lagers for eleven to twelve days, never exceeding 11° C before maturing for three months in a cellar that stays at -2° C, according to Brož.

We try fresh Budweiser Budvar right out of the tanks. It’s rich, full-bodied, and absolutely nothing like the swill most North Americans think of when they hear the name “Budweiser.” (In fact, they’re incredibly different beers made by very different companies, which is worth a read in itself if you have time.)

But it’s not the only beer lagering in Budvar’s basement.

Fresh Idea, Fresh Hops

Photography courtesy of Budějovický Budvar

Twelve years ago, Brož and three of his colleagues, Petr Košin, Jiří Smetana, and Stanislav Roháček, attended the World Brewing Congress in Portland, OR.

In the thick of the Pacific Northwest and an exploding American craft beer industry, they discovered a bevy of brewers buzzing about bines.

“We felt the enthusiasm to celebrate the beauty of the hops,” Brož tells me.

Over dinner, the four Czech brewers hatched a plan—combine the American attitude towards hops with the Czech history of making lager.

Photography courtesy of Budějovický Budvar

Returning to Czechia, Brož and his team set plans to brew a fresh-hop beer.

When hop harvest came around, they trucked 400 kilos of Saaz fine aroma hops collected from a hop yard in U splavu (200 km away) back to the brewery, brewing that same day.

The recipe started like any other for their premium Czech pale lager, with only pale malt and a double decoction. Even the first two doses of hops remained the same, but with the third dose, things veered.

Typically, for Budweiser Budvar, Brož would add the last dose of hops a half hour before the end of the ninety-minute boil. But with the fresh-hop beer, he added them ten minutes before the finish for a richer aroma, as he explained to me. Since they used fresh hops, not the pressed cones standard for their original premium lager, he said there was no need for extra time for the hops to disintegrate.

Photography courtesy of Budějovický Budvar

After hopping, the fresh-hop beer, which doesn’t technically have a name (but Brož came up with one for me on the spot—Zasr Hop Celebration), fermented at a temperature that never exceeded 11° C for about fifteen days, similar to the OG premium lager.

For maturation, though, the fresh-hop beer again veered drastically, staying in the tank for up to 400 days (as opposed to the typical 90), reaching 16° Plato, a tad bit higher than Budweiser Budvar (6.5-7% ABV as opposed to 5% ABV).

At eighty days in, Brož and his team started testing the Zasr Hop Celebration at two-week intervals.

“The first brew was so thrilling because the taste of the hops was recognizable,” said Brož. “All of us felt the burst of the hop aroma in our mouths. After that, some euphoria from the hops and American enthusiasm came to us. As we got more sips of the beer, the mildness of the bitterness and the strong body of the beer was in absolute harmony.”

The success of the experiment blew everyone away.

“All of us went through the Ph.D. studies, but not one of us expected that such a long maturation of a lager-type beer could be so dynamic,” he told me. “It was a big paradox. We didn’t expect such a high drinkability of the strong beers.”

He added, “The tradition began.”

Carrying the Technological Torch

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

Since that first fresh-hop brew, each year during hop harvest, Brož collects fresh Zasr hops for what he calls this “technological experiment,” sharing the beer with only a select few.

Budvar On-Trade Quality Manager Alexandr Vitek explained to me that Budvar doesn’t share these fresh-hop beers with the public. Instead, only with close business partners or special guests. “The fresh-hop one, you can’t get outside the brewery,” he said. “You either have to be a visitor, or you need to work here.”

Or be a group of brewers visiting from North America.

As Brož promised, he brought our team back to those tan doors. This time, instead of peeking our heads inside, we stepped over the threshold.

Around twenty of us crowded into the narrow hallway in front of two slightly rusting tanks. Encouraged by Brož, like a cheerleader on the sidelines, we poured ourselves glasses off a pigtail (a curly piece of pipe that connects to the tank to let you siphon liquid from inside). While we drank, Brož’s grin grew bigger and bigger and the buzz in the room grew louder and louder.

Brož tells us that brewing the fresh-hop beer never gets old because he finds the taste constantly changing. “It’s really amazing. Sometimes you feel the fruits; sometimes you feel the honey; sometimes you feel the strawberries,” he shared with our group as we elbowed each other out of the way to pull another pint off the pigtail. “What’s on today?”

This beer fascinated our group. That day, it seemed to drink with a fresh berry sweetness—like strawberry shortcake—with a clean, wet finish.

“I’m not getting any grassiness with this hop at all … no chlorophyll,” commented Kerry Dyson, head brewer at Brewhall Beer Co. in Vancouver, Canada. “A lot of North American fresh-hop beers are very, very grassy, or cucumber is really common; this is incredible!”

The chatter audibly rose as we huddled around Brož, firing off questions and comments.

“Do you always use single malt? One pilsner malt and nothing else,” Dyson quipped. “Then are you splitting the hops into multiple additions? What is the hop regime?”

Brož paused in the middle, “It’s always difficult to comment on it and not be drinking it,” he laughed, moving towards the tank to pour himself a splash.

As he jumped back into our group, Breakside Brewery Head Brewer Matt Kollaja stopped him.

“What happened when you went to Portland, [likewise] this trip has really put a fire under me,” he mentioned to Brož as they clinked glasses. “Thank you for sharing it.”

Brož immediately beamed, returning the compliment. “Thank you for your visit.”

To him, this was the whole point of the experiment: a cyclical melding of two enthusiastic and inspiring beer cultures.

“When the brewers came into our brewery, I always tested the beer with them. I think that we always have the most vivid discussion with the brewers when they try the tank of this beer because we are sharing not only the experience with this beer in the small area between the tanks, but it always opens the attitudes of the brewers to each other,” said Brož. “The atmosphere is always the same after several sips with the brewers!”

Budvar’s Second Fresh-Hop Celebration

While I helped myself to another half-pour of the Zasr Hop Celebration, others in our group moved on to the neighboring tank holding a fresh-hop beer made with Agnus hops.

“One year, the bitterness of Zasr was extremely low,” Brož explained. So they planned to brew two fresh-hop beers, one with Zasr (Saaz) and one with a different hop—Agnus—intending to mix the two to achieve the proper level of bitterness.

But the Agnus version turned out so well that they never blended the beers, leaving each separate.

“That’s a very important variety for us today because of Budvar 33, a special beer for the domestic market that’s more bitter,” said Brož, noting the beer gets its trademark bitterness mostly from Agnus. “It’s really an advanced bitterness, harmonic bitterness, supporting the drinkability.”

Vitek actually prefers the Angus version. “I like both of them, but I like contrasting tastes. I like the sweet, full body, the super malty body, and the bitter ending [in the Agnus],” he shared. “For me, the contrast in this beer works really well. Also, slightly more citrusy flavors make it easier to drink for me.”

Between the two, though, Brož can’t say which one he loves more.

“Zasr has a full, rich, fruity aroma. It’s much much more fruity than Agnus, and its bitterness is very mild,” he said. “But what’s strange is that sometimes we prefer Zasr and sometimes Agnus. I think the reason is that the balance—the harmony—is changing, and the more harmonic beer is always the winner!”

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

Hoppy Harmony at Budvar

The longer we spent drinking in those cellars, the more the outside world disappeared. Actually, it was more like the lines between worlds started to blur.

It’s like the start of a great joke from the ‘90s: A North American and Czech brewer walk into a cellar. Here we were, brewers from the U.S. and Canada, in the cellars of one of the most well-known Czech breweries, drinking a beer made by the tenth Budvar brewmaster with the weight of lager tradition on his shoulders yet inspired by American brewers’ love of fresh hops.

“I think that ‘harmony’ is the most frequent word I have used for these beers in my career,” Brož said with a grin, likening these beers to a symphony. “Harmony is the most important thing in creating a beer for everyday life, creating a recipe that will survive centuries.”

Vitek adds, “It’s a meeting point of modern and old-school. It is lager—good, sweet, Budweiser typical lager—with something like fresh hopping.”

We are often worlds away, yet for a couple of rounds, we are drawn together through one harmonious thread: beer.

And more specifically, lager.

“I love these moments. They are quite rare,” Brož blurted excitedly as we filed out, leaving a magical encounter behind. “But I am glad for these rare moments [because] I feel the sharing of the joy of brewing.”