Shop

Curating Craft Beer: A Growing Number of Museums Showcase American Beer Culture

Four score and seven beers ago.

Other Stories From This Author:

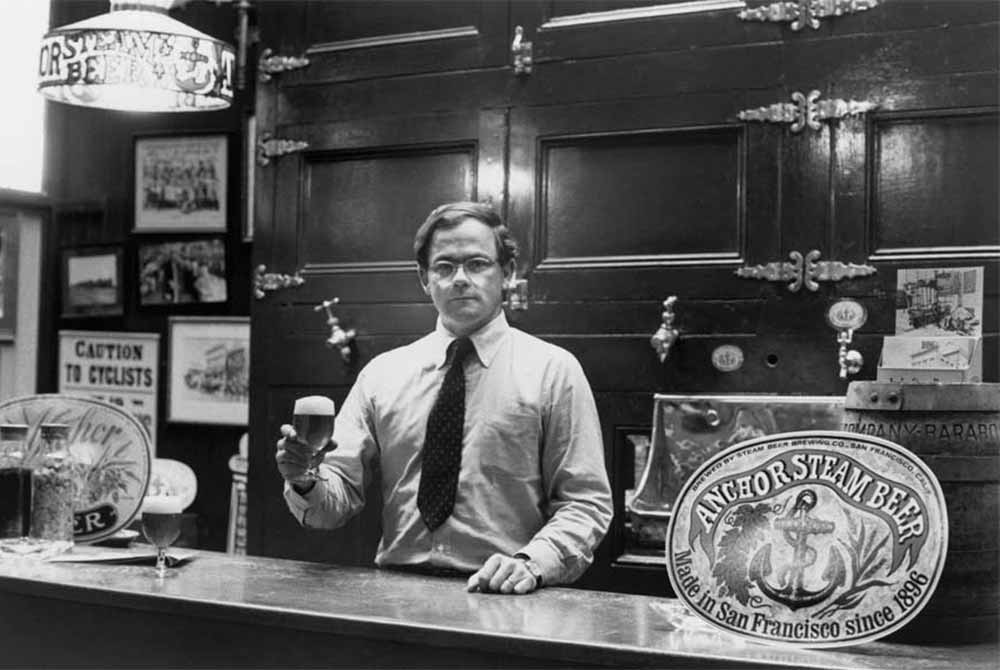

As Anchor Brewing, America’s first and oldest craft brewery, bottles its final beers, craft beer lovers around the country scramble to find a last case or two. The giant macro Japanese beer company, Sapporo, bought Anchor in 2017 but decided to close the 127-year-old brewery’s doors earlier this year. Much to the chagrin of craft beer fans nationwide. Despite this failed takeover, the brand’s status as spearheading the U.S. craft beer movement means that, for many beer lovers, the brewery represents a beloved kernel of beer history. To signal the end of an era and a tragic moment in craft beer history, people across the country liked and shared social media posts of fans holding up bottles of Anchor, including its hugely popular Christmas Ale.

People want to preserve a piece of craft beer history.

But it’s not just nerdy drinkers keeping mementos. Craft beer has become so deeply embedded in our society that historians have taken note. Many have launched their own projects and collections, showcasing artifacts and oral histories from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and making craft beer a part of the cultural lexicon.

Beer isn’t new to museums. But in the past, places like the Pabst Museum and the Heurich House Museum focused on the rise of industrial mechanized brewing in the mid-to-late nineteenth century, while exhibits at colonial plantations such as Mount Vernon and Monticello highlight brewing by enslaved persons during that period.

However, with the current craft beer movement pushing sixty, professional historians recognize the contemporary industry as a distinct and ongoing era of brewing history.

What Defines Contemporary Craft Beer as Historic?

Photography courtesy of The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History

In Illinois, you’ll find the Chicago Brewseum, the world’s first nonprofit dedicated to global beer histories. Executive Director Liz Garibay emphasizes the importance of storytelling around craft beer.

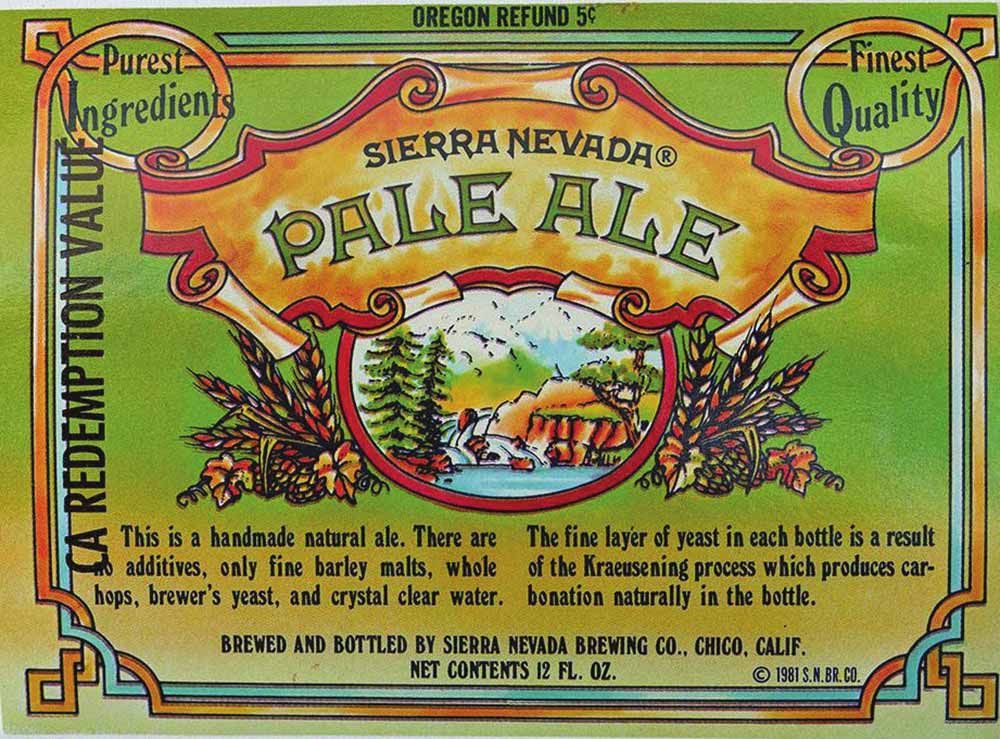

“It makes the world seem a bit small when we discuss gateway beers like Sierra Nevada Pale Ale—these experiences bring us together in a powerful way,” she says.

Theresa McCulla, a social and cultural historian and Curator of the American Brewing History Initiative at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, says the explosive growth of breweries in the last twenty years has caught historians’ attention. She notes how close to 10,000 craft breweries in the country (Brewers Association) have changed U.S. communities.

“If you live in cities or rural areas, most Americans now have a taproom in easy reach,” she says. “The visibility of craft beer has changed how we socialize—we are experiencing a return of public spaces related to beer in U.S. communities that harkens back to pre-Prohibition, with producers who are making something within and for the community.” This personal connection led consumers to become more knowledgeable about beer and interested in its history and culture, McCulla explains.

In Texas, at the Kreische Brewery Historic Site, the preserved ruins of one of the first commercial breweries in the state, Assistant Site Manager Gavin Miculka collaborates with local craft breweries such as Funky Picnic and Live Oak on living history projects.

This community link between past and present has brought beer culture into the field of contemporary history.

We also see this in a recent exhibit at the San Antonio Museum of Art, Still Brewing Art. Housed in the original Lone Star Brewing plant, the exhibition incorporated information and artifacts connecting the building’s history to the growing craft beer scene in San Antonio.

“We felt there was a continuous thread through San Antonio’s history from the period when breweries were being built in the 1880s to the 1970s when adaptive reuse (the reclamation of the site and transition into a gallery space) began, and the current moment in craft beer,” says curator Regina Palm.

How do Craft Beer Historians Select Artifacts, Exhibits, and Projects?

Photography courtesy of the Chicago Brewseum

Rich and robust, craft beer is a cultural gold mine, as full of potential exhibitions as your cellar holds bottles. So how do these craft beer historians even choose topics for their exhibitions and projects?

Connecting Past and Present

For Garibay, curating a project is about finding links between people and experiences. She wants her exhibits to resonate across time while also providing a reflection of the period.

“It’s about connecting humanity—sharing these moments where you might be able to say I have experienced this too, I am not alone in this, which is especially important post-pandemic and for members of marginalized groups,” she says.

Garibay asserts that history often repeats itself, so we must continuously catalog it in real-time. She references an exhibition she curated in 2018 at the Field Museum. “We were just over a year into the Trump presidency, and I was thinking about what Trump was saying about racism and anti-immigrant policies and realized this was not the first time we had seen this,” she explains. “I decided to focus the exhibition on nineteenth-century Chicago and the role that immigrants played in building the city, most of whom were in the beer and alcohol industry.”

Garibay contextualizes current issues by evaluating historical patterns. All through the lens of an important cultural sector like beer.

At the Brewseum, Garibay also highlights the stories of minorities who may not otherwise find a platform to share their experiences. The Brewseum’s Beer Culture Summit features panels covering lesser-known beer histories and communities, such as the history of Jewish brewers, how to equitably report on craft beer, and the lack of visibility of South Asians in beer.

Photography courtesy of the Texas Historical Commission

Similarly, at the Kreische Brewery Historic Site, Miculka aims to draw connections between the past and present.

“We want to bring in breweries celebrating beer in Texas and the Texas spirit in the same way that Kreische did,” he says.

Miculka works with breweries keen to innovate but with a focus on authenticity. For example, Live Oak Brewing, which has made beers based on original Kreische recipes, and Funky Picnic Brewing, which partnered with local maltsters TX Malt to smoke malted barley on the site as Kreische may have done.

The blending of old and new is essential to Miculka’s curation. However, a focus on the latter shows how craft beer can form personal and cultural connections. Each new beer brewed as a tribute to Kreische becomes part of the site’s history and part of local Texas beer history and brings craft beer lovers onto the site.

“Over the last decade or so, the popularity of craft breweries for community building and families has become increasingly significant,” he says. “It’s important to tap into that source.”

Storytelling and Conservation

Sierra Nevada Pale Ale label courtesy of The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History’s American Brewing initiative

In her role at the Smithsonian, McCulla focuses on resonance, storytelling, and utility. “I have to think carefully about provenance and use of artifacts and how useful an artifact could be when exhibited, whether it will lend itself to multiple exhibits and interpretations,” she explains.

McCulla must also consider logistics, such as shipping, storage space, preservation, and conservation needs.

“It’s a multi-layered decision where I think about an artifact [from] all different kinds of angles,” she says. “I look at the potential of an artifact to express its history to a museum visitor, as well as the relationship of a particular artifact to other artifacts, being careful to avoid duplication.”

McCulla has collected a broad and exciting range of pieces and stories to date, including Fritz Maytag’s microscope and a milk can used by New Belgium to store yeast when they were brewing out of their basement.

However, McCulla also emphasizes the importance of collecting artifacts reflecting world events, a newer generation, and a wider cross-section of craft brewers. McCulla’s collection reflects the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests, including objects such as Asheville, NC’s Highland Brewing Co.’s social distancing signs and branded face masks and banners from Modist Brewing in Minneapolis advocating for social justice.

“I’m always thinking about what researchers will look for in an archive in the future, and I’m especially excited about preserving different and diverse perspectives,” she says.

A sentiment Palm shared. “We’re not beer historians, but we understood the importance of including our contemporary beer history in the exhibition,” says Palm, who reached out to established veterans such as McCulla and this author to ensure that they could “connect modern San Antonio beer to our roots.”

The exhibit highlighted the city’s past and current beer scene. And the museum hosted talks on diversity in craft beer and San Antonio beer history from the Lone Star to the present.

“We wanted to connect to our community, which is impossible without considering what is happening today,” says Palm. “We aimed to tell as many stories as possible with a focus on finding stories of those who are overlooked.”

What Does All This Mean for Craft Beer?

Fritz Maytag at Anchor Brewing Company | Photography courtesy of Anchor Brewing Company

As these four curators outlined, preserving the history of contemporary craft beer is now considered a valid and accepted discipline.

For craft beer brewers and drinkers, these exhibits serve as permanent records of our culture. They offer an understanding that craft beer matters. And not just to those within the industry but to all of society.

Drinking and its subculture have cemented a place in history at established institutions like the Smithsonian and the San Antonio Museum of Art and revived older beer history sites like the Kreische Brewery—even creating new spaces, such as the Brewseum.

Craft beer is here to stay. For creators whom Garibay says “put their blood, sweat, and tears into beer,” seeing their work carefully and thoughtfully collected and represented as historical artifacts legitimizes their own craft.

In short, everybody wins. Historians preserve contemporary craft beer culture for future generations. And you can now experience expertly curated exhibits to learn more about the history and culture behind your favorite beverage.

We’ll drink to that!

Four Exhibits or Museums That Capture the History of Contemporary Craft Beer

Courtesy of The Milwaukee Lithographing and Engraving Company, 1852–1920, Lone Star Brewing Co., San Antonio, 1903, Colored lithograph on paper, 27 x 41 1:2 in. (68.6 x 105.4 cm), Museum purchase, 74.93

From D.C. to Chicago to Texas and everywhere in between, museums across the country have dedicated exhibitions to covering craft beer.

Here are a few to keep an eye on.

The Smithsonian’s American Brewing History Initiative

At the Smithsonian, the American Brewing History Initiative is an ongoing nationwide project to research and document the history of beer and brewers and Americans who enjoy beer.

Started in 2017, the project includes a multi-format archive of physical objects and oral histories specifically focused on capturing the craft beer movement from the 1960s to the present.

New Belgium Brewing Founder Kim Jordan’s role on the Smithsonian’s Kitchen Cabinet advisory board helped the project grow along with a gift from the Brewers Association.

The National Museum of American History brought McCulla on board to helm the project, which currently has a section—”Brewing a Revolution”—within its Food: Transforming the American Table exhibition.

Photography courtesy of The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History

Kreische Brewery Historic Site

The Kreische site offers a variety of hands-on experiences that highlight its contemporary local beer community. While their year-round program of activities and educational activities primarily focuses on the site’s nineteenth-century history, they also host several events and projects that specifically focus on building relationships with local breweries.

One of the Kreische’s projects includes their annual Texas History on Tap event, part of their Bluff Schuetzenfest celebration, a modern interpretation of the historic family events hosted on the site.

Texas History on Tap encourages breweries to make beers for events based on specific styles and recipes brewed at the Kreische Brewery. The unique initiative actually invites modern Texas craft breweries to become a part of the site’s history.

“The search for how to tell an authentic story appeals to a variety of beer drinkers who are interested in beer history and/or local beer,” says Miculka, who hopes to incorporate a permanent exhibition on these new iterations of Kreische Beer in the site’s new visitor center.

Going further, Kreische works with local San Antonio yeast company Community Cultures to harvest yeast from Kreische’s original brewing equipment, propagating it so local Texas breweries can make beer from the same yeast. Some might call this living history in action!

The site is also working on a foraging program with local Austin brewery Beerburg to brew with the same local plants Kreische would have had in its beers.

The Chicago Brewseum

In Chicago, Garibay brought her wealth of knowledge and expertise from her academic backgrounds—archaeology, history, and museums—to create the Brewseum in 2020.

Garibay aims to highlight beer as a cultural force of historical and contemporary value. She wants to shine a light on lesser-known elements of beer history through multiple platforms, including exhibitions, lectures, events, tours, collaboration beers, and the Brewseum’s annual Beer Culture Summit.

The Brewseum incorporates all elements of beer history—physical, oral, and cultural—and works closely with other museums, galleries, and cultural institutions, such as Chicago’s Field Museum and the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago, as well as bars and breweries to capture global beer culture and share it.

“The Brewseum has shifted from being anchored by history to being anchored by culture,” says Garibay. “ It has grown alongside the beer industry and cultural arts.”

In the future, Garibay hopes to create a permanent space complete with a bar and tasting room.

Photography courtesy of The Chicago Brewseum

Still Brewing Art – San Antonio Museum of Art

The San Antonio Museum of Art’s (SAMA) Still Brewing Art display covered contemporary craft beer in San Antonio, highlighting the diversity and dynamism of the city’s local beer scene. The exhibition, which ended September 3, 2023, chronicled notable moments in the city’s brewing.

It highlighted stories such as that of San Antonio’s first craft brewery, Blue Star, which opened in 1996 in a repurposed cold storage building and was one of the earliest Hispanic-owned breweries in the U.S., and Black Is Beautiful, an internationally significant movement started in 2020 by San Antonio’s Weathered Souls Brewing.

The exhibit bridged the city’s historical significance as the home of Texas’ first mechanized brewery to its contemporary place in craft beer culture, and architectural relics of the Lone Star Brewery are continuously visible across the SAMA site.

“There are now thirteen craft breweries within a mile radius of SAMA, flourishing and revitalizing the city, bringing people back downtown with the goal to help our community thrive, so it was essential to us to include their history,” says Palm. “We are an art museum but first and foremost a brewery.”

[Editor’s Note: This author created the contemporary beer history panel for Still Brewing Art]