Shop

The 300-Year-Old Breweries Driving a Craft Renaissance in Lille, France

Drink in the history.

Looking for More in France?

What are the oldest craft breweries in America? Some might point to the 127-year-old Anchor, which closed earlier this year. But Yuengling technically holds the title, established in 1829, along with Jacob Leinenkugel (1867) and August Schell Brewing Company (1860). But not one of these craft companies has a history stretching over 200 years. Travel to many European cities, though, and you’ll find plenty of centuries-old breweries with fairly complex histories, often surviving war, takeovers, and destruction. Take Lille, for example, a little northern French city on the border of Belgium that has made a name for itself as the “Beer Capital of France.”

While the city’s beer history stretches back hundreds of years, breweries today are reclaiming their roots, brewing new, exciting beers that stretch far beyond the area’s standard blonde ales and tripels (although they’re doing that very well, too!).

A Quick History of Beer in Lille

Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

The last city Spain owned before ceding to France in 1668, Lille sits near Belgium with an exciting mix of Flemish, French, and Belgian cultures.

A rich heritage of beer in Lille dates back to the Middle Ages. “It’s absolutely a part of the character of the city,” Hello Lille’s Destination Promotion and Press Manager Sélic Lenne told me. Perhaps owing partly to its proximity to Belgium, a country whose beer history traces back centuries, Lille lives for beer.

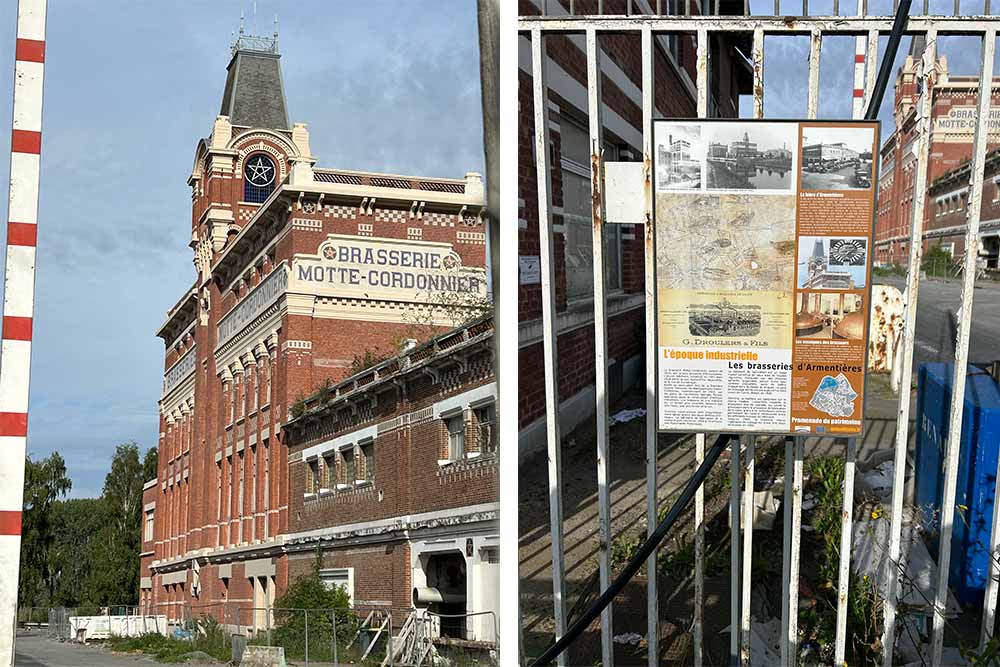

Family-owned breweries like Motte-Cordonnier, whose 370-year history makes it one of the oldest breweries in Northern France. Along with Célestin, another family-owned brewery that can trace its roots back to the sixteenth century.

In Lille, residents considered beer a daily part of life. “My grandparents used to drink a very low-alcohol beer at school,” Aurélie Baguet, co-founder of L’Échappée Bière, a beer event and tourism group in Lille, told me as she showed me around the city. Like other places in Europe, water wasn’t clean enough to drink then, so beer became a safe alternative.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Lille counted 2,000 breweries within the city and surrounding area.

But complications arose from brewing in Lille’s compact urban center. “It was noisy and complicated to deliver the beer,” says Baguet. “So years ago, they just went away.”

Plus, the growth of mass-market beers in the mid-1900s forced breweries like Célestin to sell in 1956 and Stella Artois bought Motte-Cordonnier in 1970.

But today, Lille has been reclaiming its heritage beer title.

“Now it’s different,” says Baguet, who currently counts 250 breweries in the region and 35 in the metropolitan city identified as “héritage bière,” an earned label that designates the brewery or beer bar as taking steps to welcome tourists. “[Beer] is coming back! Beer is everywhere!”

She continues, “[Beer] is a part of the culture and has clearly shaped our culture. It has become a real representation of our regional identity for French people. When French people come to Lille … clearly, beer is a part of their trip. They know that here they are going to drink good craft beer.”

Perhaps most importantly, within the last decade, the original families of both Motte-Cordonnier and Célestin started from scratch, buying back and reviving their historic family breweries with a modern twist.

One might venture to say Lille has begun its own beer renaissance.

Motte-Cordonnier, Where All the Beers Honor Historic People in the Brewery

Motte-Cordonnier has a rich history, tracing its roots through two prominent families—Motte and Cordonnier. Both had strong ties to different industries in the region, including textiles and beer.

According to Motte-Cordonnier, the brewery started in 1650 in Armentières along the Lys River. Known then as the Star Brewery, in the 1700s, Camille Cordonnier married Edmond Motte, joining the two families together at the brewery.

Over time, the brewery made quite a name for itself in the area, growing to over 1,000 employees, according to Henry Motte, the current tenth-generation owner.

The brewery provided jobs for the town along with a steady supply of potable beverages.

“Water was not clean or drinkable, so you drank beer because of fermentation,” says Henry. “You could get a beer after work and come home with your beer to have something drinkable for the family. That’s why, historically, the beer was very low in alcohol.”

For over 300 years, Motte-Cordonnier produced beer for the region, surviving multiple World Wars.

The old Motte-Cordonnier brewery which provided over a thousand jobs for the area, survived multiple World Wars but eventually closed in 2008

Built to maximize high-gravity brewing, the brewery stretched high into the air. (If you ever had a chance to visit the old Anchor brewing facility, you’d have an idea what the old Motte-Cordonnier brewery looked like.) “During the First World War, the Germans used the brewery as a milestone [to drop bombs],” explains Henry. “So the first thing the English did was explode this building. … So it actually wasn’t the Germans who destroyed our brewery, but the English!”

Although the brewery survived and rebuilt after WWI and later WWII, eventually, another threat won—consolidation.

Stella Artois bought Motte-Cordonnier in 1970 because the leading Belgian brewery wanted to establish itself in France. And at the time, “in the family, we didn’t have enough money to invest to be a leader in the market,” Henry says, noting it was a “good thing because it kept all the employees and everything working.”

But, according to Henry, while the brewery continued to function for several decades, Stella Artois eventually stopped making beer there in 1992, using the facility to bottle and fill kegs of other beer until 2008, when the brewery officially closed its doors.

In 2009, the brewery sold its entire site to a Belgian real estate investor.

Relaunching and Reviving

Henry Motte, Co-Founder of Motte-Cordonnier, pours a fresh bottle of Fernand saison | Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

Henry Motte, Co-Founder of Motte-Cordonnier, pours a fresh bottle of Fernand saison | Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

Four years ago, Henry decided to buy back the name and assets of the original Motte-Cordonnier brewery, bringing his family name back to life.

“The idea is to be a brewery which gathers all generations to drink a craft beer in North France,” he says. “Because for us, for the family, we drink a lot of beer. When my grandfather died, the first thing we did was share a beer.”

Reviving the brand goes beyond brewing beer. For Henry, it’s about bringing the memories and accomplishments of his family back to life along with the employees who used to work at the brewery.

“When we relaunched the brewery, many of the old employees wrote to us saying it was a beautiful company,” Henry told me, pointing out a Facebook group former employees started that now tallies to 800 members. “They had some good memories here.”

It’s also why all the beers are named after and reflect important people in the company’s history.

The Beers of Motte-Cordonnier

Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

For Motte-Cordonnier, beer has five ingredients. “Hops, malt, water, yeast, and the brewer, the tenth generation,” says Henry. “All the ingredients melt into one good beer!”

René Blonde Ale

For example, René, the brewery’s most well-known beer, captures the spirit of Henry’s great-great-grandfather, René Motte, who took over management of the family brewery in 1898.

The first beer the new Motte-Cordonnier launched and now fifty percent of its production, René also speaks to the brewery’s RENÉaissance. “It’s a kind of joke,” laughs Henry.

Made only with ingredients from Northern France, René includes Pilsen malt, Cascade and Pilgrim hops from a farm close by, and yeast from Fermentis.

In 2022, the 6° blonde ale won a silver and gold medal at the World Beer Awards and recently won a gold medal in the classic blonde beer category at the France Bière Challenge.

Camille White IPA

Named after Camille Cordonnier—Henry’s great-great-great-grandmother—this white IPA infused with sweet orange peel and bergamot includes wheat, Citra, Simcoe, and Brewers Gold hops.

Camille originally joined together the two families—Cordonnier and Motte—when she married Edmond Motte. According to the brewery, Camille, also known as the “Daughter of the North,” descended from a long line of brewers. She actively helped run the brewery even after her husband died, joining her son René and overcoming many challenges, including a massive fire in 1890, pasteurization, the arrival of glass bottles, and destruction from the First World War.

Today, Camille lives on through this award-winning beer, which picked up a silver at the France Bière Challenge.

“[Camille] is so very smooth … with a very orange citrus taste,” says Henry, noting this beer is his favorite. “In my opinion, white and IPA fit very well together.”

Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

Fernand

On the day I visited, Henry was in the middle of bottling Fernand, a saison named after the great-grandfather of one of the farmers who collect Motte-Cordonnier’s spent grain. “It tastes like the field,” says Henry. “In fact, people often taste the stable with oats and everything; it tastes like the farm.”

Émile Tripel

The 9° tripel honors an employee of the brewery named Émile, who started as a delivery guy at Motte-Cordonnier in 1904 before becoming a master engineer of fermentation.

Pouring a beautiful golden color, this tripel picked up a gold medal at the France Bière Challenge and a silver medal at the Lyon international competition.

From the Past to the Future

The bottling line is often only manned by the two-man brew team at the new Motte-Cordonnier brewery | Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

The bottling line is often only manned by the two-man brew team at the new Motte-Cordonnier brewery | Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

Carrying the torch is no easy task for Henry, who says that Motte-Cordonnier started small with an eight-person team brewing 1,000 hectolitres last year.

Inside the nondescript warehouse, you’ll find second-hand equipment. “We’re the fourth owner of this tank,” Henry points out. “It was the test brewery for a well-known brewery in Northern France. … So it’s very old but perfect for our usage and capacity.”

Between the mash and lauter tun, a portrait of René watches over everything. “René is always checking if the brewer is doing well,” laughs Henry. “He was a very tough guy!”

Currently, Henry says the two-person brew team brews twice a week, but they’re looking to increase their fermentation space.

Motte-Cordonnier doesn’t have its own taproom yet—only distributing its bottles and kegs locally along with a few key accounts in Paris and even Switzerland.

But the ultimate goal is to expand, eventually opening a small brewpub with a museum that showcases the family history of the brewery.

“We’re small, but we’re trying our best,” says Henry. “We are local, and we are proud to be independent.”

Célestin Where All the Beers Have a Twist

Célestin’s bottle shop in Lille, France | Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

Similar to Motte-Cordonnier, Célestin has a long lineage in brewing. And in fact, if you look close enough, you might find another connection.

In 1740, Célestin Cordonnier started the brewery, which survived until 1956, when the family sold it. In 2014, after a sixty-year hiatus, current founder Amaury d’Herbigny decided to revive the ninth-generation brewery from scratch.

So yes, technically, d’Herbigny and Henry Motte are related. Brewing is just in this family’s blood!

But where Henry decided to revive classic recipes, d’Herbigny went in a whole new direction.

On the outside, d’Herbigny appears like your neighbor down the street, a slightly older bespectacled man with salt and pepper hair in a blue quarter-zip sweater.

But inside d’Herbigny’s brain, it’s a wild, imaginative world.

“I don’t brew classical beers,” d’Herbigny told me. “My IPA, for example, is not an IPA but an IPA with yuzu. My triple, it’s a triple but with coriander and pepper from South Africa.”

D’Herbigny calls his secret ingredient emotion.

“In general, in France, most of the breweries—like eighty percent—brew a blonde, an amber, a brown, sometimes an IPA, but very classical. I don’t want to do that,” he says.

Instead, you’ll find a slew of beers (typically twenty different one-offs a year alongside some core ones) tipping the scales of creativity—pale ales dosed with ginger, double IPAs blended with orange blossom, for example.

And when d’Herbigny does brew a blonde ale?

Two of Célestin’s core beers—Hoppy Yuzu and Le Dix blonde ale | Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

La Dix Blonde Ale

The brewery’s most popular La Dix includes ten different hops from the U.K., Germany, and the U.S. “I wanted to have a blonde ale, but not a classical blonde ale,” d’Herbigny told me. “I wanted to have a blonde with more complexity.”

The approach worked with the beer winning best blonde beer in Hauts de France from Gault & Millau—sort of like a more popular version of the Michelin Guide in France.

“Whenever I organize a blind test, Le Dix is always at the top,” says d’Herbigny.

Hoppy Yuzu

D’Herbigny brewed Le Dix first and Hoppy Yuzu second, so it fits that this tasty IPA ranks as his second best-selling beer behind Le Dix.

Although, he admits, it was a conscious risk.

“It’s a bit risky to put something like yuzu [in a beer], but if you succeed, it’s very nice,” says d’Herbigny.

But d’Herbigny has certainly never been a brewer to rest on his laurels and avoid risks.

Célestin’s Brute Graceiuse stout | Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

Havane

The beer in the tanks when I visited?

A base between a blonde and an amber resting with a cigar-infused rum and actual cigars in the fermenter.

D’Herbigny brewed the 9.5% ABV Havane a year ago, and it was such a big success, “I had to brew it again,” he says, noting that the idea for the beer came from his past working for a tobacco company. According to d’Herbigny’s internet search, this might be the first time a brewer has put cigars in a beer. “I don’t think it exists,” he says.

La Brute Gracieuse

But my favorite of all the beers I tasted was the Brute Gracieuse. “Do you understand brute gracieuse?” d’Herbigny asked me with a little smile. “It’s an oxymoron.”

Typing the phrase into Google Translate, he showed me that the name means “graceful brute.”

A stout barrel-aged in Sauternes and Porto barrels between six months and two years, Brute Gracieuse is not too strong, which d’Herbigny attributes to the barrel aging used to refine the beer instead of increase the booziness. “I love this one,” d’Herbigny shared.

However, when I asked him the beers he’s proudest of, he exclaimed, ”All of them!”

A Family of Beer

Célestin Founder Armaury d’Herbigny in his shop | Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

There are two ways to enjoy Célestin. D’Herbigny runs a beer shop on the corner of Rue de la Barre and Rue Esquermoise that you can pop into Tuesday through Saturday to buy bottles to go.

You’ll find an extensive collection of barrel-aged beers here too. D’Herbigny takes his best-selling blonde La Dix and ages it in all types of casks, including Condrieu (a white wine from the Southeast of France), Sauternes, Porto, Cognac, whiskey, bourbon, and more. Plus, he’ll add select ingredients like bergamot, pumpkin (citrouille in French), tonka beans, local honey (miel), or even an ingredient we couldn’t quite land on a word for in English—Quetsche (which, according to the LA Times is “the French sugar plum” or “the Italian prune”).

The brewery itself lies not twenty paces down Rue Esquermoise. Inside, you’ll find a tiny taproom attached to the actual brewery.

D’Herbigny only opens the brewery on Saturday from 11:30 a.m. to 6:30 p.m., so if you want to drink beer here, plan accordingly.

Either way, you’ll likely run into d’Herbigny or his wife manning the shop.

A photo of Amaury d’Herbigny’s family in Célestin’s bottle shop | Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

It’s truly a family affair.

Inside the small but elegantly designed shop, d’Herbigny showed me an old family photo.

“Here is my father and one of his brothers, my grandfather. They had thirteen children. And my grand-grandfather, nineteen children. I have two sons. That’s enough, right?” d’Herbigny said with a smile.

But as to whether d’Herbigny’s sons will follow in his footsteps? “They’re too young—one is twenty-five, and the second is twenty-one,” he replied. “It’s too early.”

For now, d’Herbigny will continue to carry on his family’s traditions, building the renaissance of beer in Lille.

Lille Learns From the Past, Looks to the Future

Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

With its prosperous brewing history, Lille certainly earns its name as the “Beer Capital of France.”

New generations of brewers like Henry and d’Herbigny have taken up the mantle, pushing their family breweries forward in new directions and redefining the words “craft beer” in France.

Interested in visiting? Check out our guide to 48 Hours Drinking and Eating in Lille!