Shop

Best Breweries and Bars to Visit in Belgium

Pilgrimmage to a beer mecca.

Looking For More Travel Guides?

At the end of September, I joined a ten-day beer trip to Belgium led by Ryan and Rachel Evans, co-founders of Bruz Beers, and Peter and Frezi Bouckaert, co-founders of Purpose Brewing & Cellars.* Our mission? To visit the best breweries in Belgium.

I met Ryan during a visit to Denver for GABF in 2022. While hanging out with him and drinking his Belgian beers, he told me about how he fell in love with the culture and style during a backpacking trip in Europe.

While going up to Amsterdam, Ryan had a two-hour layover in Brussels. So he did what all good college students do: He found a pub.

“I walked in and said I’ll have a beer,” Ryan told me. “The bartender brought over a book, dropped it on the table, and walked away.” Perusing through all the beers, Ryan couldn’t find one he recognized. “The styles—dubbel, tripel, quad—I didn’t know any of it,” says Ryan, so he asked the bartender what to drink. “He said Tripel Karameliet,” Ryan reminisces. “I didn’t even know if he called me a bad word, but he brought this glass…and I’ll never forget it. I took that first sip. … ‘What is this?’ I never had anything like that in my life.” Ryan stayed for four or five more beers, walking crooked back to barely make his train.

That beer changed his life.

Now, he runs an entirely Belgian-focused brewery full-time and, every fall, leads a trip of about thirty to forty people to Belgium to share the culture and beers that influenced him.

Spending ten days traipsing around Belgium, visiting brewery after brewery and pub after pub, I can probably say this trip has changed my life, too.

Below, you’ll find our guide to the best breweries in Belgium. We’ve organized the guide loosely by city, along with a section on Trappist breweries and those off the beaten path. Feel free to jump ahead if you’d like or read the whole thing!

Look, this isn’t an exhaustive list. I’ve included most of the places we visited, plus a few recommended by others that we didn’t have time to get to on this trip. Are we missing one of your favorite breweries or bars in Belgium? DM us on Instagram (@hopculturemag), and we’ll add it to the list!

*Editor’s Note: The Bouckaerts recently entered a co-ownership with Ashley and James Lloyd, who now run day-to-day operations at Purpose Brewing.

Hop Culture’s Best Breweries to Visit in Belgium

Brussels

Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

The capital of Belgium and the site of the European Union, Brussels streets always hum, and beers flow freely.

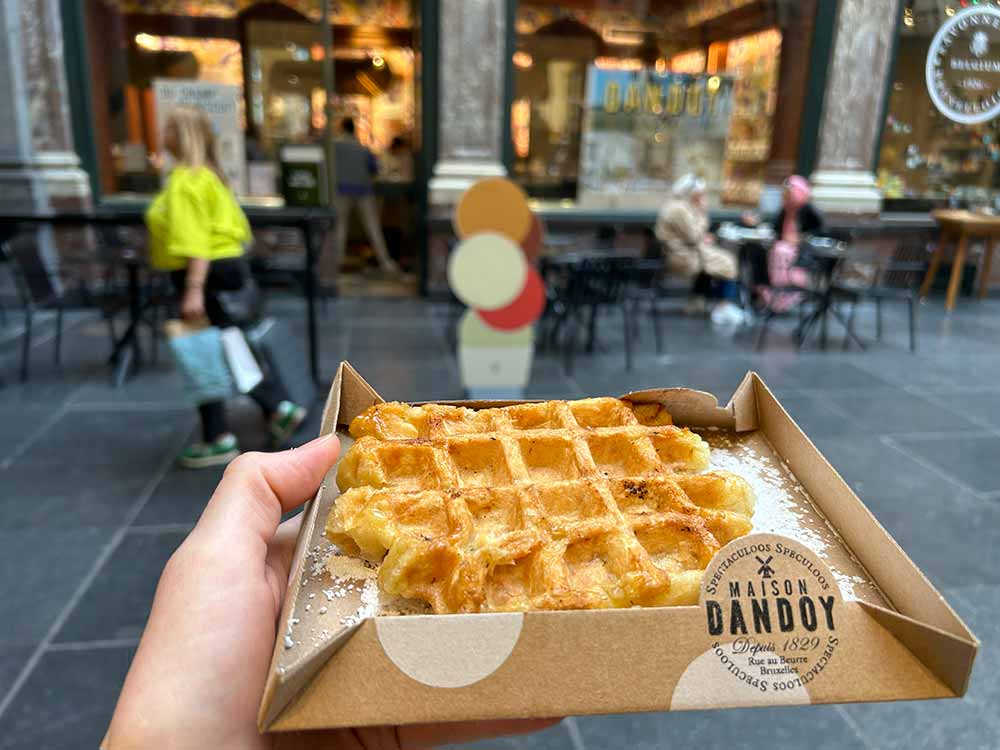

You can walk down any of the many narrow cobblestone streets in the center and wander into a great bar (or grab a waffle to go).

Brewerywise, though, despite centuries of beermaking, the city in more recent times didn’t even have two operating breweries inside its borders until Brasserie de la Senne opened in 2010.

“We had a joke at the time [we opened],” Brasserie de la Senne Brewer and Owner Yvan De Beats told me. “We said that at once, we have doubled the number of breweries in Brussels. And the previous guy who did that was probably 1,000 years ago!”

Can you guess the only other brewery operating inside the city at the time?

We’ll give you a three-word hint: lambic and gueuze.

Although, if you only counted Cantillon and Brasserie de la Senne as the two operating breweries in Brussels in the early 2010s, count yourself lucky.

They’re both fantastic breweries—one the old guard, famous worldwide for reviving lambic, and the other the new guard, known citywide for a Belgian pale ale called Zinnebir and industry-wide for one called Taras Boubla.

But times are changing. The city now has somewhere between twenty to thirty breweries. In fact, a new €90 million —opened a couple of weeks before we visited. While I didn’t get a chance to go, others on our trip said to make time for a visit.

Some still call Brussels one of the best beer cities in the world.

Here’s why.

Brasserie Cantillon

Rue Gheude 56, 1070 Anderlecht, Belgium | +3225214928

How do you introduce a now world-famous brewery single-handedly responsible for saving lambics and gueuzes from dying off? (Probably like that.)

Paul Cantillon and Marie Troch started Cantillon in 1900. But as a blender, not a brewer, Paul didn’t brew until his sons, Marcel and Robert, installed the second-hand equipment you now find in the brewery in 1939. Today, they still brew on the same equipment that survived World War II.

Cantillon specializes in lambic and gueuze, a style of beer that uses spontaneous fermentation (wild yeast) and that takes a minimum of one year but up to three to mature. By 1957, production ramped up for Cantillon, brewing up to a half-million litres. But the style fell out of favor in the mid-1900s as beers like Pilsner became popular and bigger breweries invested in making pure yeast beers that took only a couple of weeks to ferment instead of years.

One by one, the bigger breweries picked off the small lambic producers.

Except for Cantillon. Which is a bit of a small miracle because simultaneously, at the end of the ‘60s, the family had no one to take over the business. Until Jean Pierre van Roy stepped in. The husband of Marcel’s daughter, Claude, van Roy, trained in geography and worked in the music industry; he knew nothing about beer.

But again, Cantillon survived. And in the ’90s, foreign countries took a vested interest in lambic.

“Today, sixty percent of our production at Cantillon goes to export,” our tour guide, Senna Rees, shared.

Out of the hundreds of breweries operating in Brussels when first founded, Cantillon was the only operational brewery in the Belgian capital during the early aughts.

The brewery that lived persevered because they staunchly believe that the way they brew lambics is the one and true way.

Ninety-eight percent of their lambics start with sixty-five percent malted barley and thirty-five percent raw wheat grain. To get the optimal release of sugars in the raw wheat, Cantillon mash in at forty-eight degrees Celsius (~120 F) before raising to fifty-six degrees Celsius. “That’s already an hour or two just spent to make sure the wheat grain gives us the sugars and not trouble,” says Rees. However, the whole process takes four hours to ensure the wort has a wide range of different sugars and carbs to convert during spontaneous fermentation.

To walk through Cantillon is to walk through a piece of history. They’re still brewing on the original second- and third-hand equipment pieced together to work in their space. Poke your head into the mash tun, and you’ll see blades in pie-slice sections with numbers. After each mash, they’re taken out individually and rinsed; you must place them back in the same order. “It’s a puzzle to make it all fit together,” Rees explained. “It’s really specific to our brewery.”

Another three-hour boil with matured two-year hops like Saaz and Hallertau means you’ve hit seven hours before even getting to fermentation.

Only brewing on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, van Roy and his son also need to fit their schedule into a four-month period. From November until March, the cold nights (below ten degrees Celsius but preferably zero to five) provide the optimal conditions for open fermentation.

Typically, in a given brew season, van Roy and his son brew between forty to fifty batches (officially forty-six last season).

And because the lambics go through spontaneous fermentation, Cantillon believes “what lives in the brewery is important to us,” says Rees. “We’re very careful about what we’re changing [if anything].”

So I’m not sure if it’s just in my head, but the whole coolship attic smelled like a cabin I lived in at summer camp. You know, the one you return to each year and somehow manages to smell the same.

To walk through Cantillon is to smell and touch a piece of history.

Walking down narrow steps from the attic to the cellar, you’ll find a room stuffed with barrels. You can’t walk a few paces without bumping into one, a resting place for young and aging lambic.

After fermenting for one night in the one coolship, the beer goes into second-use wine barrels. “We are not interested in the flavor of the wine or the wood,” says Rees. “You just want porous wood to help ferment the lambic.”

Look close, and you’ll notice white chalk markings—numbers and letters—like some sort of sudoku. As Rees explained, the letter signifies the current season—we’re in Z, which will turn to A next spring. Whereas X represents two seasons ago. “In the blink of an eye, you know what beer it is,” says Rees.

We all pause for a moment to drink in the lambic alive all around us.

A sign nailed to one of the posts sums up this room and, in many respects, Cantillon. “Le temps ne respecte pas ce qui se fait sans lui,” it reads. “Time does not respect what is done without it.”

People covet Cantillon’s lambics, gueuzes, krieks, framboises, etc., all over the world.

But you need to travel to Brussels, the place, the air, the land, and visit Cantillon to understand the hands, the minds, and the people that make them.

L’Ermitage

Rue Lambert Crickx 26, 1070 Anderlecht, Brussels, Belgium

Part of the new-guard breweries leading a renaissance in Brussels, L’Ermitage opened in June of 2017 in an old cigarette factory not a block down the street from Cantillon.

Co-founder Nicolas De Smidt explains they got a good deal on building rent in a neighborhood considered sketchier at the time.

The first Saturday they opened, they ran out of beer. So they knew they were on to something.

Now brewing up to 2k hectoliters a year in 30-hec batches a week (“That’s why I’m so tired!” De Smidt told me), L’Ermitage focuses on wine hybrids and American IPAs, among other styles.

Although De Smidt shared, “The porter is my favorite.”

When we visited, tops among the group included a porter co-fermented with a three-year-old lambic from neighbor Cantillon on a cask engine! And a habanero-thyme sour ale called Holy Chili, made with products from a nearby BIGH aquaponic farm.

Personally, I enjoyed the Lanterne, a pale ale that had everything you want—slightly hoppy but swallowed easily with a refreshing touch of dryness at the end.

From pales to cask-engine sours, L’Ermitage showed us a new age of craft brewers in Brussels.

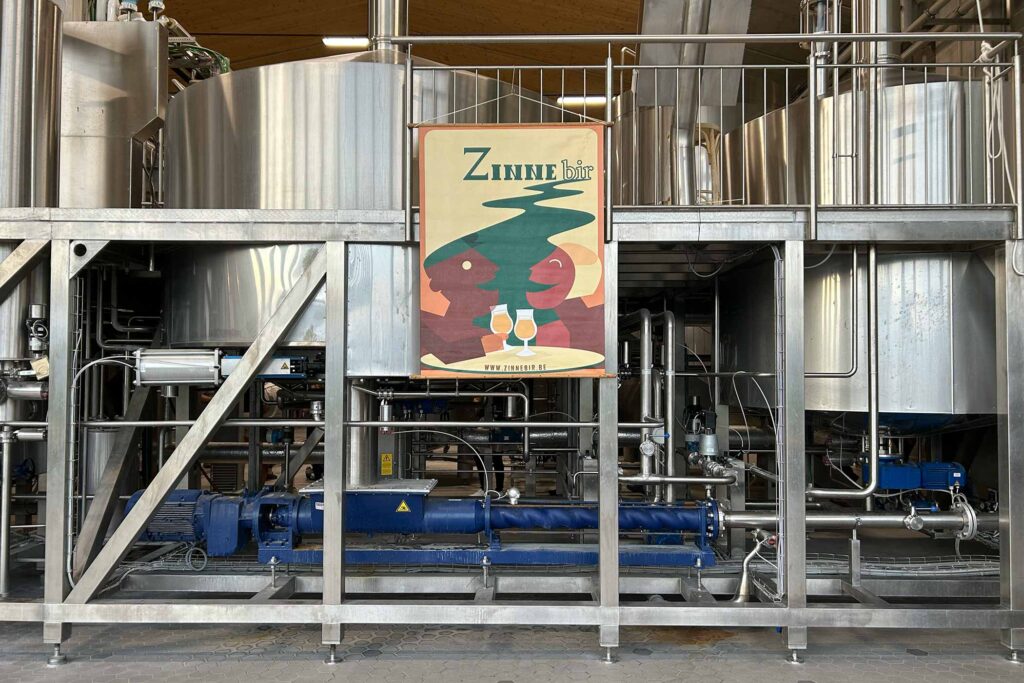

Brasserie de la Senne

Anna Bochdreef 19/21, 1000 Brussells, Belgium | +3224650751

A new landmark as much a part of the fabric of Brussels as Cantillon, Brasserie de la Senne doubled the number of operating breweries in the city in 2010 when it opened.

But you won’t find gueuze and lambics here.

Instead, brewer and owner Yvan De Beats (about whom fellow traveler and Bruz Beers Head Brewer Dave Olson explained to me, “Dude’s a hero in Belgium.”) believes to his core that behind a good beer, there should be good values.

Something Cantillon’s former head brewer, Jean-Pierre van Roy, taught him at nineteen years old. De Beats says in 1989, he met van Roy and, after a five-minute conversation, fell in love with beer.

“At the time, at least, those values were in danger,” says De Beats. “And he told me it’s worth fighting for those values.”

Although it would be another twenty years until De Beats opened his own place, the former social worker started pursuing his hobby on the side, working as a guide at Cantillon’s museum, tasting every beer and reading every brewing book he could, and volunteering at breweries for free.

“I was happy cleaning,” he told me.

All his knowledge culminates in de la Senne, which focuses on making beers that De Beats likes to drink. “It’s as simple as that,” he says. “I like to have a beer that is full of taste. … I like the approach to be simple but not simplistic, if that makes sense.”

And while things may appear simple at de la Senne, below the surface, they’re anything but (although the modest De Beats may protest differently).

For instance, De Beats designed his own fermentation vessel because he felt it treated the yeast better. The design mimics historical flat open tanks but in a vertical closed conical system. When I mentioned this seemed genius, something created from scratch, De Beats hedged. “I did nothing revolutionary; I was just inspired by what the old guys did,” he told me, noting that he has an immense respect for mixing ancient and new knowledge.

It’s why you’ll hear De Beats speak about yeast almost like it’s a god.

“We work with one of the most beautiful living beings that exists—yeast,” says De Beats. “And we cherish her. We respect her.”

Which means letting her tell him when the beer is ready, not any type of set schedule. “We always want to leave her the time to do a job without pushing anything,” he says.

Everything seems to be working.

Over the last ten-plus years, de la Senne’s Zinnebir has become a best-selling flagship in Belgium. Classified as a Belgian pale ale but technically a style De Beats calls Belgian special, Zinnebir is “sort of an English pale, but less hoppy and maltier,” he explains. They love hops at de la Senne, so De Beats made his version hoppier, drier, and bitter. “It’s the most balanced beer, and this is why it has been such a success,” De Beats says.

In Brussels, Zinnebir has reached cult status, with the Flemish media now calling places “where the cool people go Zinnebir cafes,” says De Beats. Everyone in Brussels appreciates this beer.

Meanwhile, everyone in the industry loves Taras Boulba. De Beats calls this Belgian blonde a “brewer’s beer,” he says. “It’s a beer that is simple; it’s bitter; it’s dry; it’s packed with Noble hops; it’s light in alcohol and normally everything a brewer likes.”

It’s no big surprise that De Beats first made this beer for himself and his brewers. But as friends stopped by the brewery and tried it, they went crazy for it. In stark contrast to the heavier, sweeter beer historically found in Belgium, Taras Boulba drinks light, refreshing, and quaffable. What started as a “beer never intended to leave the brewery,” says De Beats, has now become their second best-seller.

When we stopped by, we also tried Saison de la Senne, a spelt saison blended with Cantillon’s lambic (a batch De Beats handpicked himself) and aged for two years in wood.

At the end of the day, de la Senne may be a more modern brewery, but it also reflects old, cherished values. Or, as De Beats says, “I see beer as a noble product for everyone.”

Well, go forth and drink Belgian royalty.

Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen

Molenstraat 47, 1651 Beersel, Belgium | +3223067103

About a thirty-minute drive from downtown Brussels, you’ll find another of Belgium’s most recognized lambic and gueuze breweries: 3 Fonteinen.

Where Cantillon sits in a historic, cramped building off a side street in Belgium, 3 Fonteinen sprawls out in a nice new complex in the country (they have cornhole out front, for gosh sake).

Both make lambic and gueuze. Both do it their way. And both believe their way is the best.

The good thing for you as the drinker means trying both and deciding for yourself.

At 3 Fonteinen, we popped some major bottles. And that’s the move, right? Because many fantastic spontaneously fermented beers abound.

The menus (I should call them scrolls) come printed on clipboards. Flip through the numerous pages of geuze (their spelling) and lambik (their spelling) offerings.

Whisper to your friend next to you that you’re getting a Cuvée Armand & Gaston Batch Blend No. 78. Great!

They decide to pick a Prium Opal saison with Opal plums. Fantastic!

Another person mentioned they grabbed the Golden Blend and Mirabell. Wonderful!

While you’re deciding, someone else starts passing around a 1-litre jug of Oude Lambik. Amazing!

A sure sign that this brewery encourages sharing? After you settle on a bottle, the bartender will ask you how many glasses you’d like.

Head outside to the long picnic tables, where you’ll already find many bottles popped, people hopping from table to table to fill their glasses.

While I tried a lot, all very intricate and nuanced, I repeatedly gravitated back to my original choice. Kind of a classic, Cuvée Armand & Gaston will always blend one-, two-, and three-year-old traditional lambics. But every batch will be a little different; that’s the beauty of spontaneous fermentation.

The one I tried, Batch No. 78, poured a beautiful orange sunset, giving off peach, pear, and some passionfruit notes. A touch dry and wheaty on the backbone, a zippy pucker hit the back of your mouth on the way out.

Just what I wanted—nothing too crazy, but still chic and complex.

Brouwerij Hof ten Dormaal

Caubergstraat 2, 3150 Haacht, Belgium | +32477515991

On the last day of our trip, we took a short thirty-minute bike ride from Leuven, a suburb of Brussels, to this family-run farm brewery that mills its own grains on-site.

Literally out in a cornfield, Hof ten Dormaal harkens back to beer in simpler times. Owner André Janssens bought the 400-year-old family farm with his two sons, Dries and Jef Janssens, in 2009.

“The brewery started with the idea to make beer from grains on our own farm,” Dries Janssens, who considers himself a maltster, explained. They couldn’t find a malthouse willing to make such small batches, so they built their own three years ago. Now, they mill and malt mostly base malts. “I go until Vienna,” says Dries. “We’re never going to sell two tons of amber malt.”

Hof ten Dormaal also grows its own Magnum hops on almost one hectare. They used to pick them by hand every year, inviting volunteers to help with the promise of free beer and sausage. “But after two hours, we never picked our whole field,” laughs Dries. So they bought a sixty-two-year-old hop-picking machine.

“The ingredient that I start to miss in the U.S. is passion. And then you come here,” Purpose’s Peter Bouckaert told me during our visit. “It’s about passion in my eyes, but maybe I’m stupid!”

Passion abounds in bales at Hof ten Dormaal, where you’ll find beers like Witgoud, a tripel with witloof (Dutch for white leaf, aka chicory or what in the U.S. we would call endive), locally grown in the neighborhood. “No other beer like this in the world,” said the bartender, a mustachioed neighbor called Paul (or it could have been Pol) who just helps out at the brewery from time to time.

The beer comes from the 19.5-bbl brewhouse, watched over by Jef, Dries’ brother. Dirty blonde hair spilled out the back of Jef’s black trucker hat in mullet-like form. His mustard yellow Star Wars t-shirt and black denim shorts felt more in step at an American brewhouse than a family farm brewery in the cornfields of Leuven.

Chain-smoking Marlboro Reds, Jef lit each with a mini blue propane tank. After grilling our lunch, he sat with us, chilling for a second on the picnic tables next to their pond, sharing how he likes to brew.

When I asked him, “What beer do you sell the most?”

He responded with a whisper of a lisp, “Saison, which is great because I love saison the most. Tripel is easy and simple, but it’s everything I hate about a beer.”

Staunch in his views, Jef says, “I don’t read anymore,” preferring to talk about Star Wars, beer, and family.

As we sat finishing a few glasses of lambic from an earthenware urn, a couple of kids cycled by. “Those are my niece and nephew,” Jef said.

Soon, we packed up, too, hopping on our bikes to cycle back to the hotel. Our day may have wrapped up, but as we left, Jef told us, “I have to get back to work.”

Such is life on a tiny family-run farm.

Totally worth the trek, Hof ten Dormaal lets you travel back to a more peaceful time, encouraging you to take in all of the incredible ingredients around you in a glass of beer.

You won’t find a brewery or a family like this anywhere else.

Brussels Beer Project

3 Rue Antoine Dansaert 188, 1000 Brussels, Belgium

In contrast to the rustic farm, the trendy Brussels Beer Project blasts you in the face with bright neon blues and yellows. A place you’ll most likely find yourself on a Friday or Saturday night, the garish taproom distracts you only briefly from the humongous stainless steel tap wall, sporting twenty-five beers.

The neon-lit menu projected onto the side of the wall shows you several different categories of beers—“All-Stars,” “Pop-Up,” “Guest,” “Brewer’s Edition (where brewers just want to have fun),” and “Dansaert Project,” the brewery’s mixed-ferm and fruited sour hall of fame.

But if a mouth-puckering Plum Saison isn’t your thing, for instance, try any number of IPAs—hazy, kviek session, sour NEIPA, Circular Bread IPA, saison IPA, and white IPA, to name a few.

I ordered a kveik lutra lager called Dark Lutra Lager. Crisp, clean, almost like a schwarzbier, this dark lager drank a little lighter in body with a roasted coffee finish.

A buzzy place to hang, Brussels Beer Project lets you see who’s who and try something new.

Fun Fact: Brussels Beer Project has a second location in Japan I’ve also been to this past year. Well, I should rephrase. I stood in line to get into one of the best udon places I’ve ever been to in front of the Tokyo Brussels Beer Project location. I could have popped in for a beer since it took over three hours to sit down, but worth it!

Poechenellekelder

Rue du Chêne 5, 1000 Brussels, Belgium | +3225119262

Chances are, if you’re visiting Brussels, you’ll do the touristy thing and snap a selfie of yourself next to a little naked boy urinating into a fountain. Get your mind out of the gutter because Manneken Pis, first commissioned in 1388, is one of Brussels’ most famous sculptures.

Avert your eyes a little to the right, however, and you’ll see another striking sight: a tall, thin building with bicycles riding up and down the walls.

Interested? You should be because inside, Poechenellekelder gets even kookier.

The iconic beer hall’s name translates to “little marionette puppet.” Walk through the front door, and you’ll see why. Lifelike dolls with strings protrude from every corner and crevice, hanging from the ceiling next to an eclectic assortment of instruments.

Amidst the marionette mayhem, servers in crisp white button-ups and black aprons rush around in a rehearsed tango, expertly pouring bottles of beer into the proper glassware for you to enjoy.

The menu, as big as those paper ones at Buca di Beppo, shows you a selection of brunes, ambrées, Trappistes, blondes, gueuzes/lambics, and more. (Plus, Cantillon gets its own section.)

A bit overwhelmed, I admit, I stuck to what I knew first, ordering a Saison Dupont. Simply, it was amazing. Super fresh with a little bit of banana and estery character in the body and hay on the backbone, the beer presented elegantly and balanced.

Venturing a little further afield, I ordered a De Ranke XX Bitter for my second beer. Pouring a cloudy gold, the Belgian IPA drank with a stark forest floor bitterness and smooth finish.

And paired perfectly with the snacks we chose. Pro Tip: Don’t skip out on the food here!

Poechenellekelder specializes in super, super simple but just well-executed drinking food. You’ll find a selection of smaller plates and hot meals (like spaghetti—that’s a thing in Belgium), but I’d go for something listed under “Tartines De Fromages Belges” (roughly Belgian Cheese Toasts) or “Tartines De Charcuterie” (charcuterie toast).

Pick a cheese or meat, and you’ll get a big white plate served with a literal block of cheese (or cuts of meat), two slices of bread, a packet of butter, and a huge forked knife that looks big enough to cut a steak.

Rip a piece of bread, slather a smear of butter, carve off a hunk of cheese, move to your mouth, and repeat, stopping only for a sip of Saison Dupont or whatever beer you order.

A transcendiary experience, visiting Poechenellekelder felt simultaneously like simplicity and complexity at its best.

Moeder Lambic

Rue de Savoie 68, 1060 Saint-Gilles, Belgium

Photography courtesy of Tim Myers

I didn’t personally have time to stop at Moeder Lambic, which has two locations in Brussels, but many others in our group did. The well-known beer hall focuses on lambic and gueuze but also has a host of other Belgian beers on draft and in bottle.

Bruges

Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

When you think of a quintessential European town—cobblestone streets, winding narrow alleyways, a big open square where commerce commences, a huge clocktower in said square—that’s Bruges.

Almost like a mini Amsterdam, the city’s streets interweave with bridges over canals. Alleyways lined with every kind of shop imaginable—chocolate, of course. But also books, cheese, Flemish lace, Christmas ornaments, and even comic books. And, of course, beer a plenty.

Brasserie De Garre

De Garre 1, 8000 Bruges, Belgium | +3250341029

By far, one of my favorite places I went the entire trip, De Garre, might be Belgium’s best-hidden gem, literally.

Half the fun is finding the tavern tucked into one of the smallest streets in Bruges (hint: look for a rusted wrought iron gate with a “De Garre” street sign above it). But once you do, you’re initiated into a secret society.

Well, actually, once you’ve downed one of their tantalizing tripels…you’re truly a De Garre denizen.

Served in a bulbous glass, the tripel comes with stiff-peaked foam, super creamy and fragrant.

Drink, digging underneath the whitecaps to find a slightly honied, estery tripel.

Will you come up for air with a foam mustache? Probably. But that’s half the fun.

The smoothness of this 10% ABV makes it dangerous enough to warrant serving each glass with a little dish of cubed cheese.

Drink one slowly if you can, waiting before you order another because this one will hit you fast. We admit it’s hard, but try your best.

You can always leave and come back later that night, as our group found ourselves doing multiple times. Pretty much at the end of every day during our three-day stay!

If you don’t drink here, I’m not sure you’ve been drinking in Belgium.

’t Brugs Beertje

Kemelstraat 5, 8000 Bruges, Belgium | +3250339616

The beer bar that no one could pronounce became a common conversation topic.

Where did you end up last night?

“Beer cha.” “Beer ta jee.” “That one with beer and the letters “tje” in the name.”

For reference, it’s pronounced beer che.

The oldest bar in Bruges knows how to draw a crowd despite the fact foreigners can’t say the name.

Packed when we walked in, even at around ten at night, ‘t Brugs Beertje hits with locals and tourists alike.

Lucky for us, they showed us to a quiet private room in the back all our own. Perks of riding in on the coattails of one of our trip leaders Peter Bouckaert, whose time brewing at Rodenbach and New Belgium preceded him.

The menu will set you back a minute, equally packed to the brim with around 300 beers. But take the time to look through it, and you’ll find some real rarities like I did.

Okay, I lied; as with most places we stopped, I asked Bruz Beers Head Brewer Dave Olson to help me pick out a beer. But the La Vermontoise, a saison collab with Brasserie de Blaugies and Hill Farmstead, proved one of my favorites of the trip.

’t Brugs Beertje is just the kind of place to sit and find (or ask your new friend to find) your favorite beer.

Brouwerij De Halve Maan

Walplein 26, 8000 Bruges, Belgium | +32050444222

If you visit Bruges, you probably shouldn’t leave without checking out De Halve Maan.

Although I personally enjoyed other breweries and their beers more on our trip, the sixth-generation De Halve Maan still warrants an afternoon stop.

Started in 1856, De Halve Maan is the last authentic family-run brewery in Bruges.

Best known for beers like Bruges Zot, a Belgian blonde, and Bruges Zot Dubbel, De Halve Maan focuses mostly on iconic Belgian styles.

Le Trappiste

Kuipersstraat 33, 8000 Bruges, Belgium

Here’s the thing about Le Trappiste, the beer bar with a beer bible longer than the Old Testament: It has a beer bible longer than the Old Testament.

But that also means it’s a popular place.

If you go on a Friday or Saturday when the bar stays open until 1 a.m., expect to be packed into an old dugout cellar shoulder to shoulder with many other humans. Be warned: The crowd made the below-ground tavern a good ten degrees warmer (and made me relive my grubby bar-hopping college days).

Having said that, you can certainly go during an off time for a much quieter experience. You might want to, because all orders happen at the bar, and you’ll need to snag one of the mammoth laminated books lying around to figure out what you want.

Giving yourself the time and peace to pursue the pages helps you discover many treasures. For instance, the tripel Fourchette, Deus Brut Des Flanders, a brut-style Belgian beer that mimics champagne, and all forms of Westmalle and Rochefort Trappist beers, to name a few.

Brouwerij De Dolle Brouwers

Roeselarestraat 12b, 8600 Diksmuide, Belgium | +32474421273

Located a good forty minutes southwest of Bruges in Esen, De Dolle is worth the trek.

We rode about ten miles by bike through the countryside, cycling past gorgeous fields and farms. Fitting because the brewery gets its name from a bicycle club called ‘De Dolle Dravers,” translating to mad or crazy drivers.

You’ll probably just drive. But either way, at the end of your journey, you’ll find a pot of gold and brown beer.

And while the ride to De Dolle may have you asking, ‘Where the heck am I?’ (we got lost on our bike ride a few times), you can’t miss the brewery’s smiling yellow face with a red bowtie plastered above the brick brewery.

Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz | Hop Culture

An auspicious sign, the happy, quirky piece of art seems to say welcome all who come inside; good and crazy times ahead!

Because as we line up the pieces from the translation above, De Dolle Brouwers means mad or crazy brewers.

Which you might think about the gray-haired, soft-spoken man wandering around in a bright yellow suit jacket. That’s Kris Herteleer, the current owner and brewer of De Dolle, who started the brewery with his brother Jo Herteleer in 1980.

Not only avid cyclists but beer drinkers, the brothers Herteleer started homebrewing. “We tried to make beer, but in the beginning, it was not beer, so we threw it away,” laughed Kris as he showed us around. “But we improved, and after twenty-three times during three years, we have, in our eyes, better beer than in the bars.”

So on November 15, 1980, De Dolle released its first beer, Oerbier, a Belgian strong dark ale that translates to “from the source.”

A special day because, according to Kris, Sierra Nevada also brewed its first beer on November 15, 1980. “Years ago, I wrote a letter. … In fact, I said we have beaten you because the sun turns that way,” joked Kris. “And I have never had a response, so probably the internet does not work in the States.”

Much like Sierra Nevada grew from the popularity of its Pale Ale, De Dolle built its reputation on Oerbier.

But hook a right once you walk inside the brewery into the small pub, and you’ll find three to four other beers on tap.

Like Arabier, an 8% ABV Belgian strong golden ale made with Nugget hops from the famous Poperinge region of Belgium.

Special Extra Export Stout, an old-fashioned export stout.

And some purchased bottles of Still Nacht, the brewery’s coveted Belgian strong golden ale brewed for Christmas.

And if you stick around with Kris long enough, he’ll probably get excited enough to pull out some dusty old bottles from the cellar. Like the brewery’s fourteenth anniversary ale or an oud bruin from 1998, poured from a bottle caked with fifteen years of dust but tasting like refined prune juice and balsamic vinegar.

Ghent

The third city on our countrywide tour, Ghent, felt similar to Bruges but with a slightly different demographic. A college town, Ghent has a vibrant nightlife if you know where to look. Overall, fewer tourists and more locals.

For instance, at one of the city’s little Jenever pubs, we all shared a shot of Jenever, a juniper-flavored liquor that gets a dose of any variety of fruit syrups.

Probably wouldn’t catch me doing that anywhere else. But when in Ghent!

Brouwerij Liefmans

Aalststraat 200, 9700 Oudenaarde, Belgium | +3238609400

Technically, half an hour outside of Ghent in Oudenaarde, the more than 300-year-old Liefmans is also worth a little side trek.

Here, along the banks of the Scheldt River, you’ll find history. One that’s slowly dwindling with current owner Marc Coesens, son of master brewer and the first official female brewmaster in Belgium, Rosa Merckx, expected to retire soon.

For forty-six years, Mrs. Rosa, as she was affectionately known, pioneered Liefmans during a time when brewing remained a man’s world.

“She involved herself in the production of the beers,” shares our tour guide Eric, whose family owns a pub in town and began working at Liefmans cleaning cherries over the summer as a kid. (“I never drank at the brewery,” he teased. “I only did quality control.”) “Why [shouldn’t] we try other hops, why shouldn’t we try other temperatures, why shouldn’t we try other bottles, et cetera?”

Although Mrs. Rosa passed away in May of this year, her legend lives on everywhere in Liefmans, from murals and displays of her legacy on the wall to her signature on every Liefmans bottle.

“Mrs. Rosa is really a monument to the world all over,” explains Eric.

Known for its oud bruin, an East Flanders brown sour ale, Liefmans beers, such as Goudenband under Mrs. Rosa’s direction, caught the attention of everyone from the minister of Belgium to the famous English beer journalist Michael Jackson.

“Surely it’s the best brown ale in the world,” says Eric. “Called the ‘Champagne of Dark Beers,’ to the world of brewers, it’s a really great beer,” winning gold at the 2014 Brussels Beer Challenge and named Best Belgian Beer.

And surely my favorite beer, with a beautiful sparkling effervescence, notes of almost Dr. Brown’s Black Cherry soda, and a slight almost treacle sweetness.

Very unique to Liefmans’ oud bruin, the beer ferments in open-top fermenters, opening windows painted blue to repel insects to let in the naturally occurring yeast.

“This is history, and this happens now,” explains Eric. “You can make dark beer all over the world, but only here can you make Liefmans.”

As the beer ferments, a crust of yeast forms on the top. “This is heavenly; this is Liefmans. This is our secret, but it is no secret. The secret is already in use for practically one hundred years. You can smell it now.”

Because Liefmans harvest that yeast off the top, skimming it off to vats below for repitching.

“The yeast comes from the harvest from the week before, the week before, and the week before [all the way back] to 1930,” says Eric.

And although those vats are a helluva job to clean, according to Eric, he says, “This is Liefmans.”

Eric actually shows us the vessels that collect the leftover yeast; it’s a place no one is supposed to be able to go. “We didn’t come in here,” he said with a wink. Alive and kicking, we even tasted a few drops—poetry in perfect pitch.

Much like the rest of Liefmans, a three-century-old brewery continuing to make just a few beer styles their way.

At the end of the day, “Oud bruin is the basis of everything,” says Eric.

Pro Tip: Stop by the restaurant on-site. Although run by a separate group from Liefmans, the food is utterly fantastic, especially enjoyed alongside Liefmans beers.

Heilig Hart Brouwerij

Brusselsesteenweg 85 A, 9230 Wetteren, Belgium | +32488137878

You must go here. Just take a fifteen-minute drive southeast of Ghent.

A sort of impromptu visit on our trip turned out to be one of the top surprise stops in Belgium.

Located in an abandoned church that founder Hans Dusslier bought for $300k in 2016, Heilig Hart does things differently, going the extra mile in every direction.

“We wanted to brew weird beers, some with spontaneous fermentation,” Dusslier told us as he showed us around. “I don’t want to make the same beer all the time.

The former engineer also had the eccentric idea to open a brewery in a church. So he tracked down twenty churches within twenty-five kilometers of Ghent for sale, visiting thirteen.

“When I came here, I thought this is the place,” says Dusslier, who told us people thought he was crazy.

But he had faith, building a three-hectolitre brewery above the old church’s altar “to amuse me on the weekends,” he said. Although Dusslier preserved the original altar, he says, “I believe more in my altar than the one below!”

Everything at Heilig Hart has a purpose Dusslier has thought through once, twice, seven times (how many drawings Dusslier made of his plans for the brewing system and how many times he writes a recipe. “I’m a beer recipe purist,” he admits. “I want to predict what my beer will taste like in the end”).

“Brewing is like soup,” he waxes. “Everyone can do it, but making a great one … is difficult.”

That’s just how his analytical mind works. Although Dusslier admits he also trusts in nature.

Around the building, Dusslier says he found eight different hops growing, including Styrian Golding, Strisselspalt, and Hallertau. “We still have to harvest the vine in front,” he muses.

And he went to great lengths to create conditions for spontaneous fermentation, punching out holes to let Helilig Hart’s lambic-style beers (he refuses to call them lambics because they’re not in the Senne Valley) attract yeast from the world around the church’s walls.

Lagers ferment for one to two years in one of sixteen amphorae, large clay or terra cotta cylindrical vessels historically used in ancient winemaking. Dusslier considers himself a bit of an amphora aficionado, testing out ones from different countries and materials to find what works best. “To be honest, I’ve been brewing with them since 2019, and I will be happy when I retire to give some answers when I retire,” he posited. “[But for now] Catalonia, to me, makes the best amphoras.”

In the end, Heilig Hart divides its beers into three sections—”In the Name of the Father” (representative of Belgian beer culture), “In the Name of the Son” (crazy, future, experimental beers), and “In the Name of the Holy Spirit” (spontaneously fermented beers because they need a bit of spiritual luck).

We tried the Tripel , representative of the first, Custodia, part of the second, and Epiclese, in the third.

Custodia struck me. Dusslier started with the idea for an oud bruin, kettle-souring it with 1,000 liters of yogurt. After boiling, he fermented Custodia with a family sourdough culture. “My wife makes bread with it, and I make beer with it,” he said.

They made the beer twice, putting the first batch in foeders for sixteen months and the second in amphoras for four months.

The version we tried blended the two batches.

As we sipped, Dusslier’s son picked hops straight off the vine before the altar.

“Does the organ still work?” some from the group piped.

“Everybody asks that,” Dusslier said with a little smile. Apparently, it did, but the fire department declared the motor a hazard, so they needed to remove it.

No doubt that, if he still could, Dusslier would be playing music from that instrument every day. He lets his brewing philosophy and beers sing a holy gospel for now.

For our part, we’re just basking in the glow, rapt with every word.

Amen.

Stroom

Forelstraat 27, 9000 Ghent, Belgium

An American and a Belgian met in Kyrgyzstan—not how every brewery story starts. But at Stroom, in Ghent, Belgium, it’s true. Colorado brewer Farrell Styers teamed up with Ghent native and entrepreneur Carl Uytterhaegen to start Stroom, a one-hundred percent renewable energy brewery making unfiltered, unpasteurized beer.

For instance, Waltz #2, a Vienna lager, Forel, an American wheat with sweet orange, and Yak, a farmhouse ale with Sichuan peppercorn and kveik yeast.

Trappist Breweries

This wasn’t a Trappist-focused trip, so we didn’t get to all of the most famous monastery breweries. However, any must-visit Belgian brewery list wouldn’t be complete without including them.

Brouwerij De Sint-Sixtusadbdij van Westvleteren

Donkerstraat 12, 8640 Vleteren, Belgium | +3257400376

I’m not sure we need to say a lot about his brewery. Westvleteren makes one of the rarest beers in the world. Getting to visit there? Even rarer.

So, of course, during my trip, we couldn’t visit the brewery. But one of the tour leaders broke off to pick up fresh bottles for everyone to share on the bus.

So at 9 a.m. (no joke, this is a true story), I clinked my bus chalice with several others in the back of the bus and said, “Cheers!” drinking my first sip of Westy 12, as it’s affectionately known, as the bus chugged along to Rodenbach.

“Pours a Coca-Cola molasses color,” I wrote in my notes. “Smooth as black velvet or the surface of a lake in the morning, Westvleteren 12 had great notes of chocolate cherry and almost no hint of booze despite hitting a 10.2% ABV. One of the best beers I’ve ever tried!”

Brewed by The Trappist monks of the St. Sixtus Abbey in Vleteren, Belgium, in such small quantities, this Belgian quad rose to rare fandom on the sheer absence of production.

The monks brew Westy 12 once a week as a way to make money for their abbey. Sold only once a month either at the door of the monastery or a no-nonsense tavern across the street, Westy 12 vaulted to the top of any craft beer connoisseur’s bucket list simply because of the laundry list of steps and a dash of luck you’d need to try a sip from these unadorned bottles.

You won’t be able to visit the brewery because it’s not open to the public. But, if you go, you can stop by the visitors center and cafeteria called In de Vrede, where you can drink and buy beer in small quantities.

Brasserie d’Orval

Orval 2, 6823 Florenville, Belgium | +3261311261

While the brewery at Abbaye d’Orval, called Brasserie d’Orval, isn’t open to the public either, Brewmaster Anne-Françoise Pypaert gave us a special tour.

The first female Belgian brewmaster at a Trappist brewery, Pypaert, started at Orval in 1992 as the director of quality control. “At this time, there was no woman in the brewery, only men,” Pypaert told me. “But there was a change of manager. Before, it was a monk, and, at this moment, the new director was not a monk and was open to having a woman in the brewery.”

Over twenty years later, when now-former Orval Brewmaster Jean-Marie Rock retired, Pypaert took the reins.

Some of the changes Pypaert made included building a new fermentation hall, installing a bottling line that, incredibly, cranks through 40,000 bottles an hour, and changing the fermentation time of Orval to six days instead of five.

“[Previously,] we brewed Monday and transferred the beer on Saturday, but we wanted to take off the work day on the weekend,” explains Pypaert, noting the team now brews on Tuesday and, on the Monday after, transfers the beer to lagering. “The brewers are happier now that they have a weekend!”

But Pypaert quickly points out that the extra day of fermentation also helps better attenuate the beer.

Known for an addition of Brettanomyces, the Belgian pale ale Orval was first brewed at the Abbaye d’Orval in 1931.

Pypaert says the Brett addition was a “happy contamination” probably thanks to aging the beer in wood tanks during the ‘40s and ‘50s, but really ‘it’s a mystery,” she says.

Whatever the reason, the naturally occurring yeast gives Orval a distinct funkiness. Paired with some Aramis and American Tomahawk on the hot side and German Hallertau and French Strisselspalt for dry-hopping, Orval drinks with a pleasant bitterness, which some find off-putting at first.

“Your first Orval is very difficult,” shares Pypaert, who tried Orval for the first time a couple of days before her interview at the Trappist brewery. “You have to taste the second or third; after that, you like it very much or not [at all].”

Of course, if you’ve traveled to Florenville, you probably like Orval and will want to drink a few while visiting. You can do this in the abbey’s restaurant, L’Ange Gardien, in one of four ways:

Young and fresh

Young and cellar temperature

Old and fresh

Old and cellar temperature

You will get different flavors based on which combination you choose. I recommend pairing up with a friend and taste-testing the pairings side by side.

But you can absolutely not leave Orval without drinking Orval Vert, aka Orval Green, or the monk’s beer. Brewed specifically for the monks at a lower alcohol content (4.5% ABV vs Orval’s 6.2% ABV), Orval Vert is only offered on draft on-site (although they do bottle the beer for the monks or people who visit on retreats, welcoming those visitors with a bottle, according to Pypaert).

The Brett-less beer starts with the same wort as Orval but dry hops with Strisselspalt and Mosaic, switching things up to make the beer more special. “We tried it with Galaxy. … But one year, it was very difficult to find, so our supplier proposed we test Mosaic, and it was a success!” says Pypaert.

After a meal and a few beers, stroll around the abbey grounds. While the brewery only began in 1931, the monastery’s life goes back to 1132. Legend has it Countess Matilde of Tuscany, freshly widowed and grieved, stopped by a fountain where her wedding ring accidentally fell in. She prayed for its return, and a trout crested the surface with the golden ring in its mouth. Matilde exclaimed, “Truly, this place is a Val d’Or,” or valley of gold. Today, you’ll still find that trout and ring symbol representing Orval.

Much like Matilde, Orval has a history of survival, resurrecting itself after multiple wars and periods of destruction. In fact, today, you can even walk amongst the ruins of the old abbey bombed during the French Revolution.

All in all, Orval is a pretty special place.

Pro Tip: Orval, like several other Belgian monasteries, also has a cheese production facility. Pypaert also oversees all of the cheese production. You can try the dish in L’Ange Gardien or pick up a honking (and we mean honking) hunk to split with friends in the gift shop.

Brouwerij der Trappisten van Westmalle

Antwerpsesteenweg 496, 2390 Westmalle, Belgium | +3233129222

Best known for making the first Belgian tripel in the 1930s, Westmalle should also be a must-stop on your list.

We didn’t get a chance to venture into the village of West Malle in the Province of Antwerp, but I’ll keep Westmalle on my list for next time.

The Westmalle Dubbel, first brewed for sale in 1836, and the Westmalle Tripel, which hit the market in 1934, are considered paradigms of their respective styles.

Abbaye Notre-Dame de Saint-Rémy (Trappistes Rochefort)

5580 Rochefort, Belgium | +3284220140

Founded in 1230, the Abbey of St. Remy or Abbaye Notre-Dame de Saint-Rémy monks started brewing around 1595. Like Orval, the monastery survived several periods of destruction and a series of wars like the French Revolution and World War II.

Today, Rochefort’s lineup, including Rochert 6, Rochefort 8, and Rochefort 10, contain water from the Tridaine spring, one kilometer away, house yeast, special pale, and caramel malts, Hallertau and Styrian Golding hops, white and brown sugar, and a ‘secret herb.’

Towering eighty by thirty meters, the Rochefort brewhouse gained acclaim as one of the most beautiful and peculiar in Belgium. Although, you won’t be able to see it because it’s not open to the public. And you also can’t enjoy any food or beer on site. Instead, check out the town of Rochefort, where plenty of local spots carry Rochefort beers.

Off The Beaten Path

The breweries in this category don’t necessarily fall close to any particularly big city. But, good news for you: Belgium is a pretty small country. So, if you’re up for a little drive here and there, consider mapping out days to get to these breweries.

Brasserie Inter-Pol

Mont 34A, 6661 Houffalize, Belgium | +32476369639

We’d forgive you for missing the signs to Belgium’s smallest brewery (luckily we didn’t because we had an excellent bus driver!), Inter-Pol, because you’re not looking for a typical taproom. You’re literally trying to find Owner Pol Ghekiere’s basement in the village of Mont, in the Ardennes.

Inside, you’ll find a built-in pub and thirteen-square-meter brewery where Ghekiere can make eighty-litre batches.

Ghekiere built everything himself, digging out the foundation with his brother. All across the property, you’ll find quirky touches. An old merry-go-round turned sitting space, rugs on the ceiling, a boar’s head.

Sporting a striped blue shirt and John Lennon-like glasses, the craggy-faced Ghekiere stoically slings beers behind a lampshade of salt and pepper hair.

Stay long enough, and he’ll lead you in the brewery’s official song, written on parchment paper that he can unroll from an open doorway behind the bar.

The beers range, including Ghekeire’s stable, the Witte Pol, which pours a cloudy, pale, wet-sand dark gold, smelling like spiced lemon peel or lemon verbena balm. Very light, the Witte Pol falls heavier on the more-spiced-than-citrus spectrum with a dash of mild saltine cracker.

If you can only drink one, I recommend the Peated Pol, which seemed to be our group’s favorite for its heavy smoke aromas yet super light body.

Visiting Inter-Pol is like drinking in your best friend’s basement. Oh, wait. You almost are.

Brasserie d’Achouffe

Achouffe 32, 6666 Houffalize, Belgium | +3261288147

From the basement to the big dogs. If you weren’t convinced to visit Inter-Pol, consider this: You get a twofer here. There’s a dirt path that winds down from Pol’s house to the well-recognized gnome-obsessed Brasserie d’Achouffe.

Now, I’m not the biggest fan of d’Achouffe’s beers, but I’m only one person.

You can still have fun hanging out in the pub (with gnomes). If you do go, I recommend the Houblon Chouffe, a fairly hoppy, sturdy-bodied Belgian IPA.

Brasserie Dupont

Rue Basse 5, 7904 Leuze-en-Hainaut, Belgium | +3269225639

If you love saison, you should probably visit the godfather of this farmhouse style.

Started in 1844 as the Rimaux-Deridder farm brewery, Alfred Dupont bought the brewery in 1920. Today, a fourth generation of the family runs the brewery known worldwide for making one of the epochal versions of saison.

Historically brewed for farms as a refreshment during the summer, saison started as a lower-ABV beer.

Today’s versions push much higher, with Saison Dupont cresting 6.5% ABV.

Made with Pilsen barley malt, Golding hops, Saison Dupont carbonates in the bottle for a super effervescent, bubbly start. Pouring a cloudy copper with a whipped cream-like head, Saison Dupon fizzes with scents of Lemonheads, lemonade, freshly baked bread, and pepper.

This is rustic beer at its best, making the trip to Tourpes in Western Hainaut, Belgium, a treat.

Brasserie à Vapeur

Rue du Maréchal 1, 7904 Leuze-en-Hainaut, Belgium | +3269662047

I believe we were supposed to visit here, but the brewery team got COVID, so we swiveled and ended up in Heilig Hart’s church, literally.

Still, I want to list this brewery here if you have better luck because it’s supposed to be a pretty special experience.

Just know that you need to plan to get here.

This unique steam-powered brewery (the last in Belgium), Brasserie á Vapeur, opens the last Saturday of every month.

On that day, owner Jean-Louis Dits suits up in his blacksmith-looking apron to make beer using a slide valve Watt twelve-horsepower steam engine.

In addition to beer, Dits hosts a banquet in the farmhouse next door during the brew day, that can include things like bread from a wood-fired oven, slow-cooked ham, and cheese. Nearly all made with Dits’’ beer.

Sounds like this would have been an incredible addition to our trip, so hopefully, you have a chance to go!

Brouwerij De Ranke

Rue du Petit-Tourcoing 1a, 7711 Mouscron, Belgium | +3256588008

Founded by friends Nino Bacelle and Guido Devos, De Ranke gained a reputation for making some of Belgium’s best small-batch specialty beer in West Flanders.

Also some of Belgium’s hoppiest beers.

Like the aforementioned XX Bitter that I had at Poechenellekelder and XXX-Bitter, which get their distinct hoppiness from Hallertau and Brewer’s Gold hops.