Shop

Our Favorite Breweries and Bars to Visit in Czechia

Na zdraví!

Other Stories From Czechia

At the beginning of April, I joined a five-day beer trade mission to Czechia led by The Czech Ministry of Agriculture.

Over the last half-decade, this department has organized an immersive trip for Canadian and American brewers, introducing them to Czech producers, ingredients, and beer styles. The goal is to encourage trade between countries and educate us on Czech beer styles and culture.

It’s an intense trip that takes us around the whole country, visiting, in total, about twenty different places (not counting all the pubs where we would then go out at night).

Even after just one week in Czechia, it’s pretty apparent that Czechs LOVE beer.

Need proof?

Well, for almost three decades, the people of Czechia have consumed the most beer per capita out of any country in the world. In 2021, Czechs drank 184.1 liters per person ???? (Kirin Holdings). For context, the United States ranked seventeenth with only 72.6 liters per person.

Suffice it to say that the Czechs take their beer seriously. And they’re finally sharing their beer culture with the world for the first time in centuries.

“If there is any justice in the world, this country would be better known for its beer culture,” beer journalist Evan Rail told us as we sat in a monastery brewery that has been making beer since 993. “But justice is in short supply.” Rail would know. He’s lived in Czechia since 2000, becoming a de facto expert on Czech beer culture.

A Short History of Beer in Czechia

The Czechs have a long, tangled history with beer production. Several of the breweries we visited on the trip have existed since the 1300s, 1400s, or even 1500s, with others starting in the 1800s.

But over the twentieth century, both the Nazis and Russians occupied Czechia, making conditions less than ideal. The Czechs had to adapt just to survive.

“The situation in our country was de facto unchanged after 1948, with exceptions, individualities did not arise, logically it was not possible in the communist regime, any individuality was suppressed there,” wrote Pilsner Urquell Master Bartender Champion Lukáš Svoboda in an email to Hop Culture.

From a brewing perspective, Czechs couldn’t push exports or promote their beer culture.

For instance, Bavarian brewery Josef Groll first brewed a pilsner in Plzeň, Czech Republic, in 1842. Technically, the word pilsner means “from Pilsen” (or Plzeň) in Czech. And if you say Piju Plzeň in Czech, that directly translates to “I’m drinking the town of Plzen.”

Today, the style has become one of the most widely consumed worldwide (even Miller Lite cans include the word “pilsner” on them). But while millions of people drink the style, far fewer recognize what the word “pilsner” means and where this beer style originated.

In other words, the Czechs invented one of the most-drunk global beer styles but haven’t received equal recognition.

Compare this lack of awareness to other European countries. For example, in France, the government heavily controls the appellation for Champagne and Cognac; in Germany, the Cologne region controls the appellation for Kölsch.

No protected geographic regulations or official recognitions exist for pilsner.

But that’s changing with each group of brewers that visit Czechia or with each person who decides to pilgrimage to the birthplace of pilsner, for example.

At least for me, spending five days visiting brewery after brewery and pub after pub vastly expanded my knowledge of Czech beer culture. And now I can bring that back to share with you, our readers.

But reading about it is only half the battle (and fun); I highly encourage you to plan your own trip to this beer-drenched country.

If you do, hopefully, you can use our guide below to the best breweries and bars we visited in Czechia as a starting point.

Editor’s Note: Look, this isn’t an exhaustive list. We’ve simply included most of the places we visited, but there are literally hundreds of spots. Are we missing one of your favorite breweries or bars in Czechia? DM us on Instagram (@hopculturemag) or email us at [email protected], and we’ll potentially add it to the list!

Hop Culture’s Best Breweries to Visit in Czechia

FUZE

Na Florenci 2139, 110 00 Nové Město, Czechia

After dropping my bags at the hotel, I met up with a few folks for our first beer of the trip at FUZE. The newly opened brewpub in Prague absolutely gleams. Floor-to-ceiling glass windows stretching three stories encase a very modern state-of-the-art brewery.

Located in the lively Masaryčka district of Prague, FUZE pulses. You might consider this flashy spot the future of brewing in Czechia.

Case in point: the glass brewing equipment. Yes, you read that right.

FUZE Co-Owner Jan Murdoch wanted a splashy space to make a statement. This means that, in addition to the glass brewing kit, you’ll also find vivid colors splashed on the walls and the bathroom—well, it’s a statement piece.

But the beer was decent. I’ll admit this was my first beer of the trip, and after the fifteen-minute walk from our hotel in unseasonably warm eighty-degree weather, any beer probably would have hit the spot.

But for a taste of something new, snazzy, and glitzy in Prague, FUZE fits the bill.

Červený Jelen

Hybernská 1034/5, 110 00 Nové Město, Czechia

Červený Jelen, otherwise known as the Red Stag in English, so named for the large red deer that greets guests as they walk into this gorgeous multi-floor bar and restaurant was the second stop of our first afternoon in Prague.

Housed in a former Anglo-Austrian bank, this absolutely gorgeous space includes four spaces—The Bank, The Club, The Vault, Lounges—and two open beer gardens during warmer weather.

We ordered Šnyts of Pilsner Urquell, the only beer they serve here. And they serve it at its peak, unpasteurized, and delivered by a special cistern directly from the Plzeň brewery.

Behind our table, twelve brown horizontal tanks towered from the basement. As PULT Tapster Magda Hoppova told us, this is supposedly the world’s tallest beer tank tower, rising nine meters, or three floors.

Each tank weighs 710 kg once filled with Pilsner Urquell, which the brewpub will only serve for four to five days after tapping. In total, the beer tower, when completely full, equals 6,350 liters of Pilsner Urquell, weighing an incredible 9,500 kilograms.

We did our part by drinking a couple of half-filled glasses of the good stuff.

But you could spend an entire afternoon and evening here drinking pilsner and eating grilled meats from the restaurant’s two-ton inferno grill, imported from Washington state and fed with nine-month-only dried beech and oak wood from the Czech Křivoklátsko forest.

Yup, it’s that kind of place.

PULT

V Celnici 1031/4, 110 00 Nové Město, Czechia

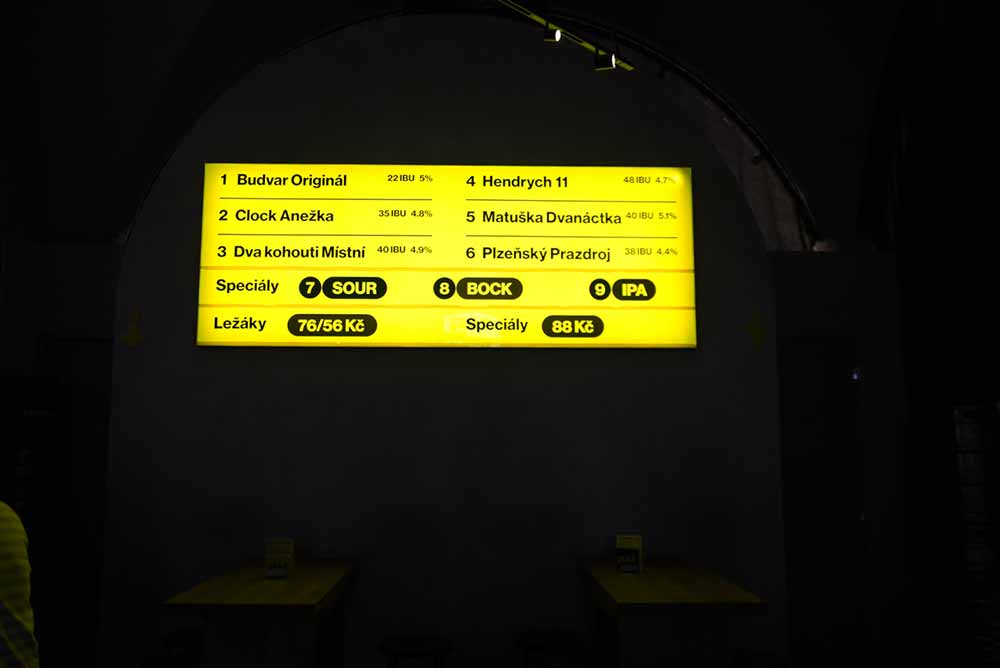

Our group spent quite a few nights at PULT, a bar part of the super well-respected Ambiente group of restaurants in Czechia. Walk into the tiny shotgun-style pub, and you’ll find a menu with just six main beers on draft. Uniquely, PULT opens up these spots on their tap list once a year. Those that they choose stay on for the entire year.

Or, as the pub succinctly puts it, “Six perfectly poured lagers on tap.”

This place just slaps. And they treat each and every one of those six beers on tap like royalty. Whether you order a Hladinka, Šnyt, or even Mlíko, you can rest assured that the tapster behind the bar will execute every pour perfectly.

Those like Hoppova, who has been working at PULT as a tapster for the last five years.

Favorites from the current menu in 2024 included H11 from Hendrych.

I can’t tell you how many Hladinkas of this beer our group drank throughout just a couple of days. Suffice it to say, “a lot” will have to do.

Hendrych’s flagship beer has a fair amount of bitterness for a Czech pale lager, but mysteriously, the more you drink it, the more drinkable it becomes. Sounds like a riddle, but it doesn’t have to be.

Personally, my favorite was Pivovar Clocks’ Anežka.

When we first walked into PULT, Hoppova helped me navigate the menu.

Do you want something hoppier or maltier, she asked me.

Maltier, all the way.

Hoppova didn’t steer me wrong. Anežka has a slightly malty sweetness supported by a resinous character that balances everything super crisp and clean.

But whichever of the six beers you get, you can’t go wrong. Just don’t leave PULT without ordering one of the toasted sandwiches, a tray of meats and pickled things, and the pickled camembert with black garlic.

And just accept right now that you’ll probably end up at PULT more than once during your trip.

Dva Kohouti

Sokolovská 81/55, 186 00 Praha 8-Karlín, Czechia

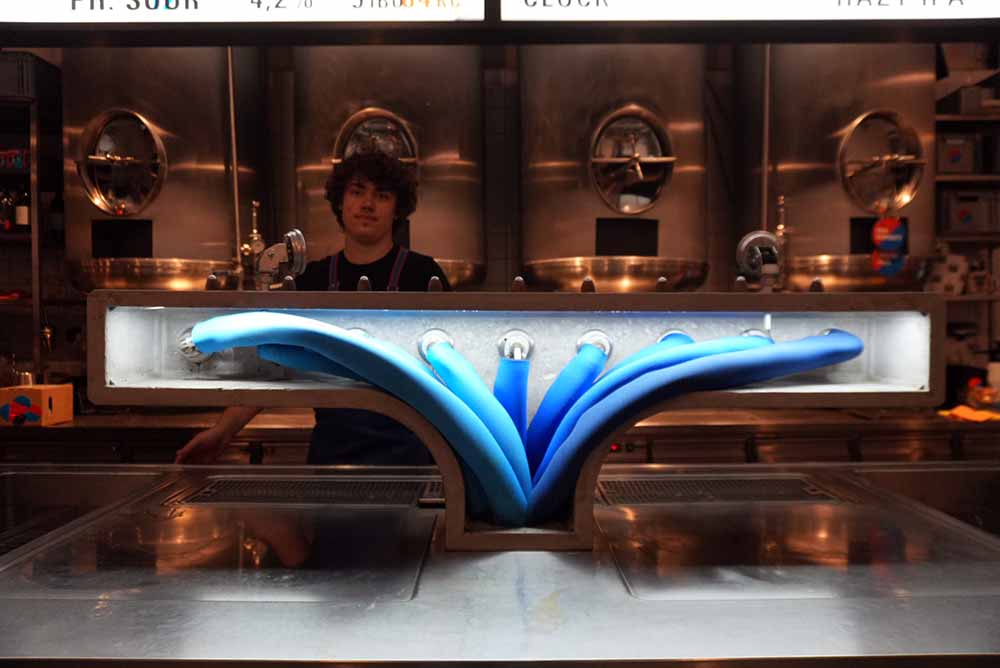

If we weren’t hanging in PULT’s tiny space, we were sprawling out across its sister pub, Dva Kohouti’s massive cobblestoned beer garden.

Every single person I talked to before this trip, whether they’d been on the mission before or simply traveled through Prague, told me I could not leave the country without going here.

It’s easy to see why.

Like any pub the Ambiente group operates, they give unparalleled care to the beer.

If you walk in when they’re not busy, you’ll find a tapster washing glasses. If you walk in when they are busy, like a seven-hour line out the door on a Monday afternoon, you’ll find a tapster washing glasses.

The rules are followed to a T here—glasses sit chilling in a cold water bath, each cleaned before being expertly poured. (Need a refresher on how this group likes to pour beer? Check out our guide to the proper Czech pours.)

The go-to here?

Místní Pivo 12°, the pub’s flagship Czech pale lager. It’s the one beer you’ll probably find on tap all the time.

But again, you can’t go wrong with whatever you drink. This is a must-stop when you’re in Prague.

Lokál U Jiráta

Vodičkova 696 /26, 110 00 Nové Město, Czechia

Another project from the Ambiente group, Lokál pubs can be found all over Czechia, seven alone in Prague, one in Brno, and one in Plzeň (more on that below). Each has its own unique identity and fingerprint on the idea of the Czech pub.

For instance, Lokál U Jiráta, the youngest and smallest of the Lokál family that you can find on Vodičkova Street in Prague.

The story here comes from innkeeper Josef Jirát, who, in 1887, decided to serve pilsner from the local brewery straight to folks on the street.

At this Lokál, the place to be isn’t inside but a few paces away on the street. Little wooden ledges set up on the wall of the pub encourage you to put down your drinks and huddle in groups, drinking alfresco.

When we visited on a Tuesday night, the place bumped with people spilling onto the light-drenched street. Just get a beer round, post up in the street, and drink the night away.

Břevnov Monastery Brewery of St. Adalbert

Markétská 1/28, 169 00 Praha 6, Czechia

The oldest male monastery in Bohemia has been brewing beer at Břevnov Monastery Brewery of St. Adalbert since 993. Yup, that’s a pretty long time. In fact, according to the monastery, Břevnov recorded the first written mention of brewing beer in Czechia.

“This one is old,” beer journalist Evan Rail jokes. Rail has lived in Czechia for almost a quarter of a century, spending most of his time drinking nad writing about Czech beer. He brought us to Břevnov because it’s one of his favorite breweries.

And because they make one of his top five favorite beers—

When I asked Rail what made this one of his favorites, he responded, “It just has a special taste. I like it.”

He adds that the Saaz hops have a unique flavor here, “like ginger or chewing on a cinnamon stick, woody and spicy.”

For much of the monastic brewery’s history, they sourced hops from an abandoned Saaz hop yard owned by a friend of the brewery in the Saaz region.

The over seventy-year-old hop bines produced those aforementioned characteristics. Today, the Benedictine monastery actually has its own Saaz-producing hop yard, which grows forty percent of the Benedictine Saaz used in its beers.

In their světlý ležák, Břevnov also adds Magnum hop extract because the Benedictine Saaz has only 1.9 percent alpha acids; they need the Magnum oil for a touch more bitterness.

A double decoction also adds a nice body, color, balance, and drinkability to the beer. (If you’re looking for a full breakdown of this beer, we highly recommend checking out Rail’s piece in Craft Beer & Brewing.)

Today, the brewery makes 4,000 hectoliters a year, selling ninety-six percent of their twenty different beers in Prague out of the current brewhouse they rebuilt in 2011. But still, when you’re at Břevnov, it feels like you’re drinking a piece of history.

U Fleků

Křemencova 11, 110 00 Nové Město, Czechia

At most places in Czechia, Czech dark lager won’t be the most popular beer on the menu. But not Pivovar U Fleků. Without a doubt, the best beer here is Flekovský Tmavý Ležák 13°.

This is by far and away the best Czech dark lager I’ve ever had. And I’ve tried lots of excellent versions here in the States.

U Fleků has just perfected this recipe over time. Lots and lots of time.

One of the smallest private breweries (yet the largest restaurant) in Prague, U Fleků originally started as a brewery over half a millennium ago in 1499 and has been brewing ever since. Started by Vít Skřemenec, the building shifted hands a few times and survived a few wars until finding its way to Jakub Flekovský, who bought it in 1762, giving the brewery its current name—U Fleků.

This brewery has become known for one beer—tmavé pivo (Czech dark lager)—which it has brewed for over 180 years.

Using a 140-year-old mill, U Fleků grinds their own combination and proportions of roasted dark and light malt, which they assured us is a secret known only to the current family. But after just a little research, we found the beer includes fifty percent pilsner malt, thirty percent Munich, fifteen percent caramel (toffee), and five percent dark roasted malt.

The milled malt then goes to the mash tun, where it’s mixed with water at 52° C before going through a double decoction.

After adding Saaz hops, the beer cools in a coolship before fermenting for thirteen days and lagering for up to six weeks.

The 13° dark lager should have an ABV above five percent (the degree refers to the strength and gravity of the beer pre-fermentation). But U Fleků lists this beer at 4.6% ABV, meaning the brewery under-attenuates the dark lager, leaving behind unfermented sugar that gives this beer its uber creamy, red-carpet-smooth mouthfeel.

This Czech dark lager looks like perfectly tempered chocolate with the perfect shine and viscosity.

As you drink your way down the mug, this beer performs a magic trick—it is sweet but not too sweet, roasty but not too roasty, and looks heavy but drinks like a silky dream.

Nothing out of whack, light and not too malty, Flekovský Tmavý Ležák 13° is a beautiful beer to drink in U Fleků’s epic beer garden.

Not sure I need to say more.

Pioneer Beer

nám. Prokopa Velkého 303, 438 01 Žatec 1, Czechia

After leaving Prague, we spent a day touring the top hop producers in the Žatec region, one of the three main hop-producing areas of Czechia. We rubbed well-known varieties such as Saaz and Sladek along with some unknown ones such as Kazbek.

We spent the night in Žatec, where we found the semi-new Pioneer Beer.

A pretty modern brewery that only opened in 2018, Pioneer represents the new wave of craft beer in Czechia.

Situated in a former hop warehouse in Žatec, Pioneer is absolutely gorgeous inside.

Walk in, and you’ll immediately notice gleaming silver tanks.

Pioneer represents a mashing of tradition and innovation. Right alongside lagers like Pioneer’s well-known Rezident, you’ll also find a smattering of more contemporary American styles, including hazies, DDH IPAs, and even a Cold IPA.

I went for the COMFORT, a single-hop Czech pale lager featuring Saaz Comfort, a mildly bitter variation on Saaz.

The beer’s elegant balance of hops and malt had me returning not once but twice. I think that says it all.

Plzeňský Prazdroj, aka Pilsner Urquell

U Prazdroje 64/7, 301 00 Plzeň 3, Czechia

Every year, more than half a million visitors travel worldwide to Plzeň just to visit Pilsner Urquell to taste the world’s most iconic unfiltered, unpasteurized pilsner.

Call it a pilgrimage. Call it a religious experience. Walking under those cream and tan arches stamped with MDCCCXLII and MDCCCXCII (1842-1892) makes you feel like you’re on hallowed ground.

Which, if you love pilsner, you technically are.

A white-haired man with a cherubic face and black, thin-rimmed glasses greeted us. Over his navy long-sleeve waffle knit, a light black vest with the words “Pilsner Urquell Brewmaster” stamped over his heart. Václav Berka, the thirteenth brewmaster at Pilsner Urquell, joined a lineage stretching all the way back to Josef Groll, the man who literally invented the pilsner here, the first one leaving the brewery on October 5th, 1842.

Groll, a German brewer, brought a new type of yeast to Plzeň. Combined with the city’s uniquely soft water, malt from their own malting plant, and Saaz hops grown not too far away, he created this amazing new style.

When Groll opened the first barrel on November 11th during a holiday celebrating at a big fair in the town square, people were shocked, as Berka tells it. Instead of finding a dark, cloudy beer popular then, Groll raised a glass full of this golden, clear beer with a nice, foamy head.

People loved it, and the pilsner soon grew in popularity, popping up in Prague, Vienna, London, Paris, and even America over the next thirty years.

Now retired, Berka served as our tour guide for the day.

We started in the brew hall with its massive direct-fire copper kettles, traditionally fueled by wood, then coal, and natural gas today.

Pilsner Urquell believes the copper kettles produce the basic parameters for pilsner. A triple decoction creates sugars that caramelize on the walls of the copper kettle, giving the beer its characteristic golden color and caramel flavor and aroma, along with a low-modified Czech Moravian barley and a special mix with about five to six varieties.

As he showed us around, we peppered him with questions.

How many beers have you drunk here?

How many Pilsner Urquells do you drink in a year?

“I already answered this,” Berka said with a sly smile. “I am very bad at math.”

As we make our way down into the underground aging caves to what he calls “the place where pilsner was born,” he encourages us to touch the walls and the floor and feel the history.

“I hope I will die here,” he says, half joking. In fact, Berka grew up here. Berka’s father worked in the fermentation department, and as a kid, Berka would spend time in the nine kilometers of cold cellars and underground tunnels.

He says if you ever get lost and cannot make it back to the gate, “just follow the water.” The condensation on the walls drops into gutters that flow down towards the way out.

The average temperature of the cellars sits at 5° to 6° C. In the past, blocks of ice were brought in from local rivers to make the area even colder for maturation.

Following history, Berka says they still ferment Pilsner Urquell in wooden casks and mature the beer in wooden oak barrels to achieve its famous drinkability.

We grabbed a taste of the unpasteurized, unfiltered Pilsner Urquell right off one of these wooden barrels. Again, drinking it in the chilly cellars was almost a religious experience.

Now celebrating its 182nd anniversary, Pilsner Urquell is a brewery you can’t miss if you’re traveling to Czechia.

Pivovar Proud (Elektrárna)*

U Prazdroje 64/7, 301 00 Plzeň 3-Východní Předměstí, Czechia

On the Pilsner Urquell campus is a brewery you’d probably miss if we didn’t tell you about it. Past the yellow building stamped with Pilsner Urquell, past the pub crowded with drinkers sporting mugs of pale gold liquid, past the courtyard that Berka assured us is filled in the summer with those dancing and drinking, you’ll find an unassuming building with a brick smokestack towering into the sky. In front, polished gleaming steel kegs with a blue band and letters pulsing like an electric current: Proud.

As we crowded beside Berka, a petite woman with curly black hair appeared at his side. She tied a jacket around her waist over a blue Proud polo.

Lenka Straková has been the brewmaster at Pivovar Proud for the last three years. Here on the Pilsner Urquell grounds, she and her team make new, experimental beers meant to test the market, electrify the palates of Czech beer drinkers, and push their beer boundaries to new heights.

Here, you’ll find beers like an English pale ale brewed to educate Czech consumers.

“With this beer, we’re saying, ‘Hey, in England, they drink [this style] as normally as you drink the Czech draft,’” Straková explains as she pours us a taste. “British ale is also very close to the profile of Czech draft beer, but it is still top-fermented … and at the end a drinkable, refreshing light beer.”

A beer bridging cultures, TheMže actually has a double meaning.

The second half of the name refers to the Mže, a nearby river. Straková says they add “The” to the name so that when pronounced fast, it sounds similar to the Thames, the well-known river that winds through London.

Accordingly, Straková adjusts Plzeň’s incredibly soft water for this beer to mimic the not-so-soft water found in London.

Although, Straková says with a laugh, she’s “not that brave to brew with totally hard water.”

She says that they get halfway to English water for this pale beer.

The malt bill also reflects a mixture of cultures, featuring Czech pale and English pale malt, which Straková explains is slightly higher in proteins, giving the beer a bit more body and maltiness.

Hops include English varieties such as Challenger, Jester, and U.K.-grown Cascade. “They give the beer this lighter, hoppy aroma but are still herbal and floral, quite similar to Czech hops,” says Straková.

An English top-fermenting yeast strain called ESB finishes this pale ale, which indeed has the lovely crispness of a Czech pale lager combined with the earthier, herbaceousness of an English pale.

Or Yuzu Pale Ale, a simple pale ale recipe with a fifty-fifty mixture of imported yuzu fruit and sugar added at the end of brewing to mix well with the wort, Straková explains. “Everything ferments, and just the aroma and part of the bitterness character from the fruit goes into the beer,” she says. “Normally, if we say this is a fruit beer to our visitors, they all expect something sweet, but it isn’t. It’s regularly bitter with a nice aroma of citrus.”

If Berka represents the past at Pilsner Urquell, then Straková certainly encapsulates its future.

*Editor’s Note: Some time after our visit, Pivovar Proud rebranded as Elektrárna. For our experience, while we were there all of the equipment was branded with the Proud name and everyone we talked to at Pilsner Urquell referred to the brewery as Pivovar Proud, so we will continue to use that name in this piece. Unfortunately, Pivovar Proud is not generally open to the public, but you can find their beers at pubs all around Plzeň.

Lokál Pod Divadlem

34, Bezručova 315, Vnitřní Město, 301 00 Plzeň 3, Czechia

Right in the heart of Plzeň, you’ll find Lokál Pod Divadlem, serving uber fresh Pilsner Urquell from the brewery just blocks away.

When we visited, groups of friends spilled out of the pub and into the beer garden on the street.

A part of the Lokál family, you know the beer here is treated right.

This is a great place to go if you leave Pilsner Urquell and need somewhere to keep the day rocking into the night.

Budějovický Budvar

Karolíny Světlé 512/4, 370 04 České Budějovice 4, Czechia

Rivaling Pilsner Urquell in size and popularity, Budějovický Budvar has its own unique way of making its premium lager—Budweiser Budvar.

Captained by Adam Brož, the 10th brewmaster in Budvar’s 130-year history, Budvar’s process starts with eight copper kettles on top and stainless steel kettles on the bottom.

To make Budweiser Budvar, Brož starts with Moravian Hana malt, a two-row Czech barley. He takes the wort through a double decoction before adding fine Saaz aroma hops in the form of pressed cones.

Brož spent extra time detailing the double-decoction process, a crucial part of making Budweiser Budvar. He starts the hop water at 37° C before heating the mash to 50° C. At this point, he pumps a third of the volume into a separate kettle, heated to 65° and up to 75° C; he repeats the process a second time.

“It took me four minutes [to explain to you] now, but in reality, it takes four hours!” Brož exclaims, noting that the extra step “creates beer we want, and we won’t change it in the future.”

According to Brož, a typical brew day lasts ten hours.

A short walk takes us to the cellar, where Brož assures us, “We’re approaching not the empty but the full glasses!”

Brož says Budweiser Budvar lager never exceeds 11° C during an eleven- to twelve-day fermentation, and the cellar stays at -2° C for three months of maturation.

We try fresh Budweiser Budvar right out of the tanks. It’s rich, full-bodied, and absolutely nothing like the swill we probably all drank in college. (In fact, they’re incredible different beers made by different companies that’s worth a read in itself if you have time.)

But the best is still yet to come. We walk back to a cellar, doors agape, and Brož tells us there’s a secret inside.

We have the opportunity to try a set of incredible, experimental fresh-hop beers that never leave the brewery. It’s an unforgettable experience, just the cherry on top of our visit.

Pivovar Ferdinand

Táborská 306, 256 01 Benešov u Prahy, Czechia

Named after Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, whose assassination started WWI, Pivovar Ferdinand was actually purchased by the heir to the throne about seventeen years before his death.

Operating a classic floor malting facility next to the brewery makes Ferdinand one of a kind, especially since they’ve been doing it for over a hundred years with very few technological changes in a little town thirty miles south of Prague.

Chances are, if you’ve had a beer with Weyermann’s Floor-Malted Bohemian Pilsner Malt, Ferdinand malted it to the tune of 2,000 tonnes per year.

Walk into the malthouse, and you’ll find grains lying on the floor in different plots and stages of germination. A man jumps on what looks like a small tractor and zooms across the floor, rotating the kernels.

The process is intense and documented excellently by Jeff Alworth from Beervana if you’re more curious about the technological specifics.

In a separate building, we’re guided around a four-vessel brewhouse capable of making 250 hectoliters per batch. Although the equipment in the brewhouse looks like it came from a museum, they assure us that everything is in working order and used for brewing once a month.

One batch of the brewery’s flagship lager starts with five tons of malt and 400 kilograms of Saaz Premiant pellets.

After a double decoction, the beer ferments in open fermentation vessels for seven to eight days at temperatures up to 10° C before lagering for two months at 2° C

We mount the stairs in one final building; the words Ferdinand on the side of the wall guide us up to a small tasting room.

Pouring a clear, deep gold, Ferdinand’s lager is a little more spritzy and alive than some of the other lagers we’ve tried during the trip.

Visiting Ferdinand is a genuinely incredible experience. You can see one of the most underrated but crucial beer ingredients—malt—from floor to foam to faucet. Makes the beer you drink at the end taste all that more fresh and alive.