Shop

Brewing a Brooklyn Sake Lager with Five Boroughs and Kura Sake

Sake. Sake. Beer.

Meditative music wafted through the uncomfortably warm room. My forehead furrowed in concentration as tiny beads of sweat slipped down onto my eyebrows. I stretched my hands forward as far as I could extending my arms past my ears like Michael Phelps in an Olympic 100-meter relay. Between my thumb and forefinger I gripped a tiny metal canister similar to the red pepper shakers found on the checkered tables at pizza joints. Tipping the jar over sent a plume of mossy-colored flakes fluttering across an industrial-sized table brimming with an even layer of rice. I settled into a rhythm.

Shake-shake-shuffle-pause.

Shake-shake-shuffle-pause.

In a spiritual stupor, I methodically continued my foxtrot around the counter…

Shake-shake-shuffle-pause

Shake-shake-shuffle-pause

…until I had covered every inch of the white-washed grains in an invisible mist. I cracked a sly smile.

With a few calculated flicks of the wrist, I had just finished a crucial step to making sake.

Sequestered in a steamy room in the back of Brooklyn Kura, New York State’s first sake brewery, I’d come to the newly-opened taproom for another first. The rice base I’d inoculated with a mold called Koji wasn’t bound for a bottle of a fermented rice drink, but rather the mash tun at Five Boroughs Brewing Co. Located 12 streets south in Sunset Park, the 8-month old brewery neighbor teamed up with Brooklyn Kura to make a very special beer. The koji rice lager, called Sunset Kura, featured a grain bill split equally between the rice we fermented at the Industry City facility and the Pilsner malt we added at the Five Boroughs brewery over a week later. Half sake-making, half beer-brewing this collaboration experiment signaled a first for both breweries.

Brewed in Brooklyn

I handed the shaker back to a congenial man sporting a ruddy crop of chin hair. He pushed up the sleeves of his ginger waffle-knit sweater. Like me, he was beginning to sweat.

Brandon Doughan, the co-owner and brewer at Brooklyn Kura didn’t seem as mesmerized by the process as I did. Afterall, he’d been doing this for a while.

A former homebrewer, Doughan’s fascination with opening a sake brewery began back in 2013 when he met fellow co-owner, Brian Polen, at a mutual friend’s wedding in Japan. The two visited a traditional sake operation together and brought the idea to start their own place back to the States.

On opposite sides of the country – Brian in New York working in analytics and technology for American Express and Brandon in Portland serving as a biochemist for the Knight Cardiovascular Institute at Oregon Health and Science University – the two kept in touch.

After Brandon moved to Brooklyn in 2016 the pair began scouting locations for their business.

As Brandon and Brian tinkered with Japanese grains, Kevin O’Donnell and Blake Tomnitz had already been toying with a different type of grain less than a mile away on 47th St. Opening Five Boroughs Brewing Co. in August 2017, Tomnitz and O’Donnell had joined forces after careers in the corporate world.

With similar backstories, Five Boroughs’ friendship with Brooklyn Kura officially began when Blake and Kevin invited the sake duo to visit the brewery. “We brought them out, showed them around, talked about the trials and tribulations of starting a brewery, and tried some beer,” said Nick Griffin, the Head of Brewing and Quality Management at Five Boroughs. Armed with sake samples themselves, Brandon and Brian soon turned the conversation from brewery build-out tips to a possible collaboration.

“There’s a lot of overall misconception that sake is distilled, but sake is actually brewed,” said Doughan. “We started talking about some of the steps in sake making and how we might overlap those with beer brewing. Combining the two ways beer and sake produce sugar became the genesis of the beer.”

Fully understanding the creation of Sunset Kura requires a deeper dive into the similarities between making sake and beer.

Yeast, Sugar, and Fermentation oh Sakamai (sake-my)

Although they seem like two disparate drinks, beer and sake share a few basic principles of brewing.

When beer is brewed, the grain is mashed and the enzymes in the grain convert the starch to sugar. While the base of sake undergoes a similar process, because the rice is milled so heavily, those necessary enzymes do not naturally exist. Instead, sake makers add an organism called Aspergillus Oryzae (Koji) to a small percentage of the rice. This living entity grows mold on the rice, which in turn produces amylase, creating the needed enzymes for starch conversion.

That thin cloud I’d sprayed over the rice wasn’t only a meditative move, but the beginning of the mold-growing process. By spreading Koji over the rice, I had essentially initiated a simultaneous mashing and fermenting process.

Now, don’t be fooled, making sake requires much more than a few spiritual shakes. I had only joined in for a very small sample of the long, arduous, and meticulous procedure.

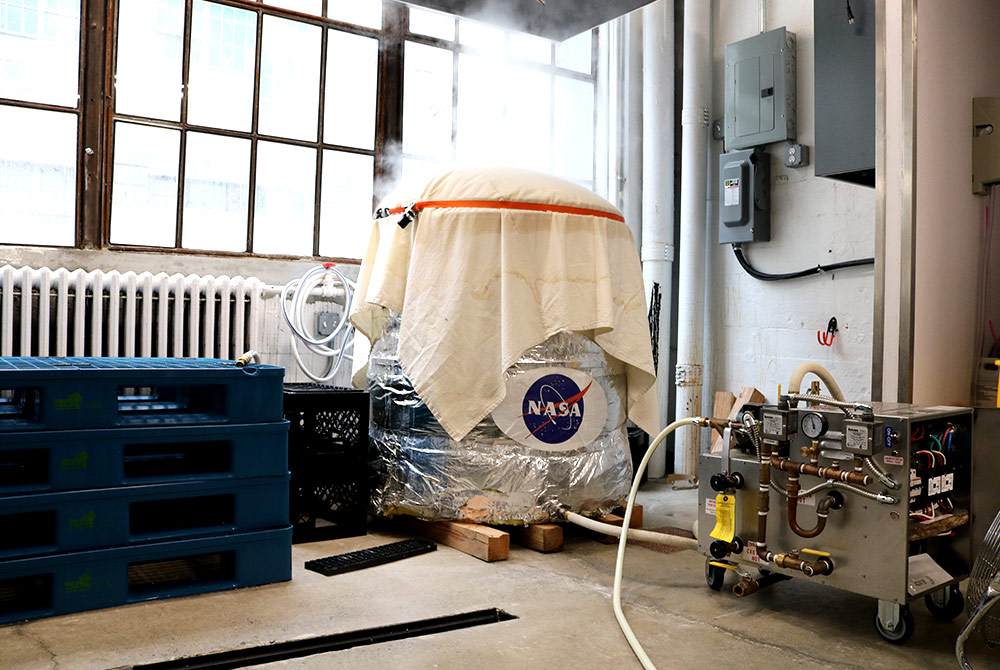

Deceivingly complex, the whole sake-making process began even before I arrived at 68 34th Street with Kian Oveissi, the CFO at Five Boroughs Brewing Co. With many steps ahead of us Brandon had already started steaming the rice. Housed in a UFO-esque basin sporting a NASA emblem (a joke at Brooklyn Kura hinting at Brandon’s science background), the Sakamai, or specialized sake rice with a very starchy center called Shinpaku, needed to soak in water before we could use it. This initial water absorption stage helps the Koji grow on the rice.

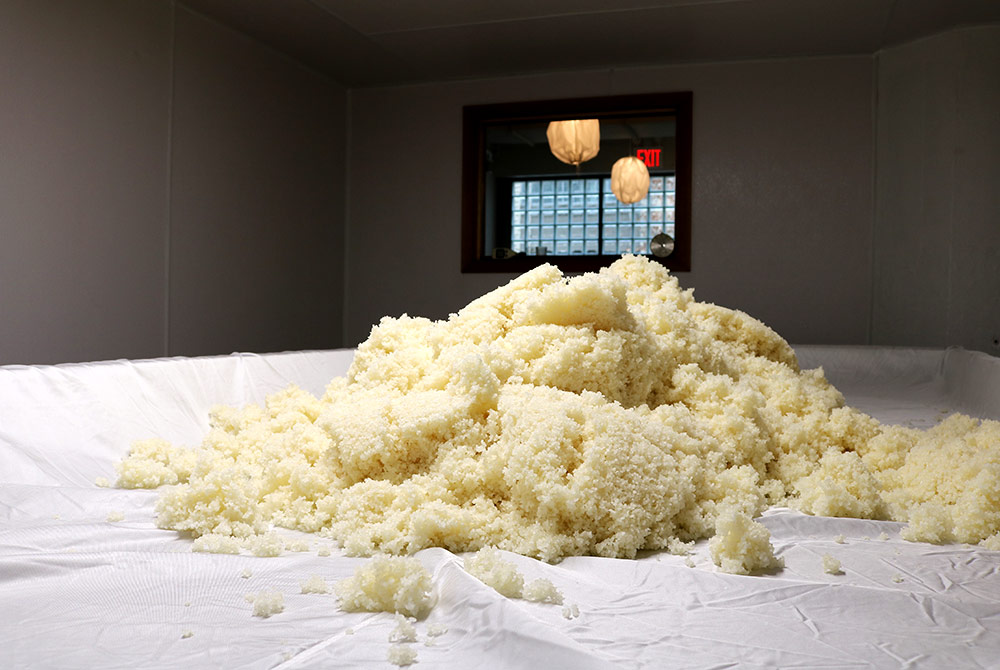

While we waited, we prepped the tiny storeroom for the next step, setting up pallets with what looked like large sushi rolling mats on top. When the rice finished cooking we shoveled the grist into buckets and laid it out in even layers to dry. “You want to cool the rice down to where it is still warm enough that the Koji organism will grow, but it’s not so hot that you will kill it,” said Doughan. Think of the Koji like yeast pitched inside of a fermenting beer–if the liquid becomes too warm or too cold the yeast will die. After briefly waiting for the rice to cool, we carried it in cloth bundles into that sauna-like room, dumping the white mountains onto a large chest-high table.

We took turns shaking the Koji out over the thick layer of rice, flipping the kernels over, and repeating the performance for an even coating on both sides. Kept between 30-43 degrees Celsius (or 86-110 degrees Fahrenheit) the specifically steamy conditions allow the Koji to break down the starches in the Sakamai.

“You want to be mean to the Koji a little bit, but you start off by being very nice,” said Doughan. Native to Southeast Asia, Koji likes a hot, humid environment. Once the Koji starts growing around the rice, however, the humidity of the room needs to be lowered. This slightly callous step causes the Koji to seek out the moisture in the middle of the rice. “As the Koji starts working into the center of the grain it makes a little time capsule of amylase,” explained Doughan, creating fermentable sugars for alcohol.

Now, all we had to do was wait.

Sunset Kura in Sunset Park

A week later Brandon and Brian made the short trek south to Five Boroughs brewery with the finished Koji in tow to brew the rice lager. After much deliberation, the two breweries settled on a recipe split equally between Koji and Pilsner malt.

“We were trying to decide if we wanted to do 10 or 20 percent rice, but it was evident right away that if we were going to make this beer we wanted to take a risk,” said Griffin. “When we look to collaborate we don’t do it just to do it. We want everybody to bring their unique product into the mix and combine it with our own style.”

Adding 50 percent cultured rice to the mash with 50 percent extra pale Pilsner malt was a scary step. “We thought originally because there was so much rice in this beer that we’d have a tough runoff and the mash would stick, but turns out that didn’t happen and it was actually one of the easier brews we’ve done,” said Griffin.

Despite concerns, the brew day went to a T. After mashing the Koji and Pilsner malt, Griffin and Doughan added Hallertau hops early in the boil. A traditional noble German hop low in alpha acids, the Hallertau added a decent amount of bitterness and aroma to the beer. From there the koji rice lager underwent a standard cold lager fermentation, spending almost six weeks in the tank. Although slightly worried the beer would lose some of the Koji essence during fermentation, Griffin noted the flavor integrity of the beer stayed intact.

“We thought if it doesn’t turn out it doesn’t turn out, but it would be a worthwhile experiment. This was one of the times where the beer exceeded the expectations,” said Griffin

Brimming with a unique citrusy, rice character, Sunset Kura masterfully melded the taste of sake with the structural body of lagers.

“I like that they left it unfiltered. It looks like a Hefeweizen, but tastes like a really crisp and clean Pilsner with a little bit of the Koji earthiness,” said Doughan.

Griffin rebutted, “It’s funny talking to Brandon because he drinks sake every day and doesn’t really get the rice flavor [from the beer]. But for all of us who drink beer, we’re all like, ‘Dude it tastes exactly like sake!’”

The Future of Collaboration Fermentation

To celebrate the success of the Koji Rice Lager collaboration, Five Boroughs released Sunset Kura in their taproom on May 5th during their Kickoff to Summer in Sunset Park party, inviting people to come try the beer alongside a sample of Brooklyn Kura sake.

“I don’t know if I’ve ever seen a sake and a beer together,” said Kristin Stranc, a Brooklyn Kura fan who’d come to Five Boroughs specifically to try Sunset Kura. “I think it’s really brilliant and wildly successful!”

Similarly, Sunset Park resident Kazuhiro Abe found the beer to be a perfect sake-beer hybrid. “It is very nice with so much flavor from the rice Koji,” said Abe. A transplant from Japan who works at the sushi restaurant, Juku in Chinatown, Abe notes that in Japan it’s hard to make sake, let alone good sake. Sunset Kura managed to successfully translate the flavor of sake through the body of a beer. “It has a little sweetness, but not too much. It is a little sharp and great for the summer. I really love it,” said Abe.

Worth the sweat and arduous brewing process, the success of Sunset Kura has Doughan and Griffin already looking toward the future. “We’re bouncing ideas back and forth for the next beer,” said Griffin at the brewery during the release party. “We’ve done the light lager thing at this point, so the next beer will be in the complete opposite direction just seeing where we can take Koji and sake yeast and mashing it with beer brewing techniques.”

With only 12 blocks separating these two Sunset Park breweries we expect the sun has only begun to rise on the future of these funky fermentation experiments.

“It’s a cool idea for breweries to collaborate with companies making other fermented beverages,” said Griffin. “Not many breweries can say they’re right down the street from someone making high-quality sake. We’re extremely lucky.”