Shop

Thar She Blows!: Breweries That Come Down to That One White Whale

Call me Ishmael.

Check Out All of Our End-of-Year Content!

Best Hidden-Gem Places to Drink in 2023

Best Breweries of 2023

Best Places We Traveled for Beer in 2023

Flagship beers or the white whale are a staple of craft brewing. They’re the old reliables, the ones you always see on tap, in cans, and on liquor store shelves. The time of year doesn’t matter. When you want a flagship, like a good friend or a trusty insurance company, it’s always there.

Not every brewery has a flagship. Some prefer putting their eggs in a bunch of baskets, spreading the role of brand ambassador among an array of beers instead of choosing one. Either approach has its merits. (If that wasn’t the case, then every brewery would either have a flagship, or they wouldn’t have one at all. Simple math.)

The “flagship” designation confers status. The message is clear: If you want to know what a brewery is all about, this beer is the best way to make introductions. But some beers rise above the level of “flagship.” They represent their brewery, no doubt, but they become an entity unto themselves: Icons in the wider market, whose acclaim spreads beyond the brewery, beyond town lines, beyond state lines, and even across coasts.

Once upon a time, we called these beers white whales, offerings you’d have to camp out for with no guarantee of even getting a single bottle; or tailgate delivery trucks to buy before the herd wipes out the stock; or call a friend to do these things for you, the ultimate slacker’s ticket to tasting beer royalty.

Today, no one needs to stalk brewery drivers for a measly four-pack. What hasn’t changed is clout. 3 Floyds’ Dark Lord is still Dark Lord. Lawson’s Finest Liquids’ Sip of Sunshine might be brewed in Connecticut, and you might be able to find it in your local Trader Joe’s, but it’s still Sip of Sunshine—a classic IPA among craft beer’s ocean of IPAs. Mercy of mercies, times have changed. Access has expanded. The fight for rarities is over.

But what does that mean for the breweries who make goated beers like these?

The More Things Change, The More They Stay The Same

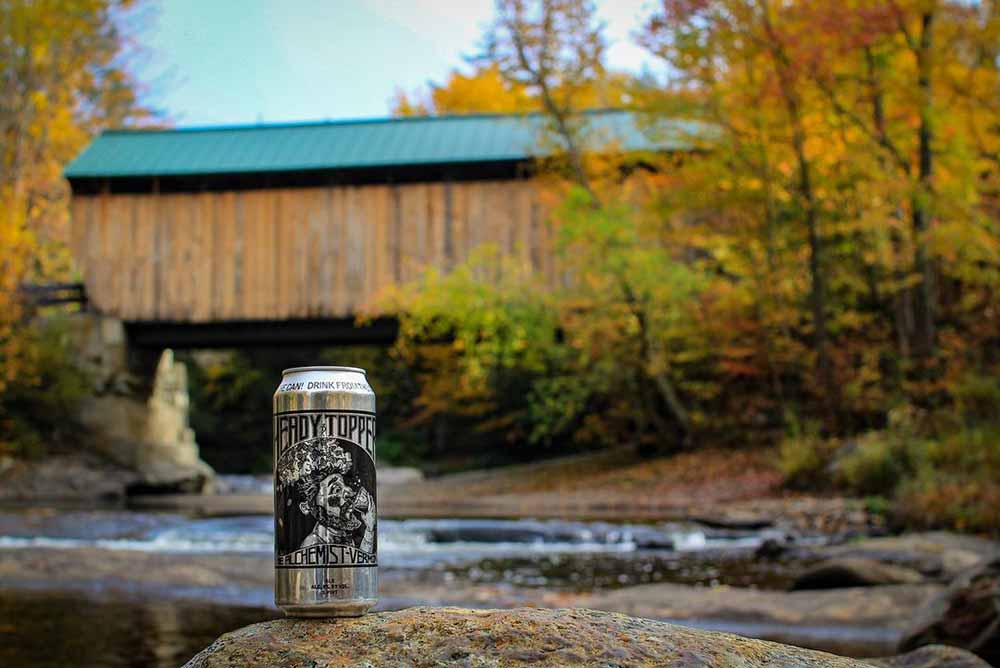

Photography courtesy of The Alchemist

Nine out of ten Americans hear the word “Vermont” and think of cheddar cheese, ice cream, maple syrup, and beer. Out of those nine, five will replace “beer” with “Heady Topper,” synonymous with “Vermont beer” since its legend began two decades ago when John and Jen Kimmich opened The Alchemist brewpub in Waterbury. Fast forward to 2011, when they opened a small production brewery in the village and snagging cans of the granddaddy of all hazy IPAs meant battling mountainous local traffic around the brewery’s location.

Maybe idling on Route 100, sandwiched by disgruntled ski bums and jonesing beer nerds, is your idea of fun. For everybody else, the situation was dire—so dire, in fact, that the brewery closed to the public in 2013. Nobody should have to idle in their car for the chance to buy beer that might run out before they pull into the parking lot.

Fortunately, that day came and went for The Alchemist, and so too for other breweries married to a beer as iconic as Heady Topper. John couldn’t be happier. “There’s not really a need anymore,” Kimmich says, citing the craft beer industry’s growth in the last ten years. Around 3,000 breweries operated nationwide in the U.S. in 2013. As of 2022, that total has ballooned to over 9,000. With that much choice in the market, the motivating factors that (literally) drove consumers to choke roads in Waterbury no longer exist. People can camp out for hot new releases if they want to. They just don’t have to.

“I’m not gonna say that it was a bad thing,” Kimmich notes. “To have people waiting in line for your beer is flattering as could be. But I think everybody’s glad that’s over.”

Hardcore beer geeks were known to tailgate delivery trucks, on the hunt not only for Heady Topper but other hard-to-get Vermont beers (like the aforementioned Sip of Sunshine). That simply isn’t healthy. “It was a bummer,” Kimmich reflects. “We were being led by the people, because we just had to do what we could to keep up. It doesn’t give you that chance to where we are now, where you actually have this beautiful flow to your business.”

The Alchemist’s new Stowe location, which opened in the summer of 2016, is, in a word, bigger than its past places of residence. A cylindrical tower adorned with a stunning Afrofuturist mural overlooks the brewery as well as the outdoor beer garden; indoors, there’s a beer cafe where you can crack a can on-site, an especially nice benefit when you miss out on a limited can drop (a’la Just Say Gay or Skadoosh, The Alchemist’s rotating hop series). No one has to ride bumpers or throw elbows for a four-pack anymore.

A White Whale Beer By Any Other Name Would Still Be Beer

Photography courtesy of Grace Weitz

On the other side of the U.S. from Stowe, in Windsor, CA, Russian River Brewing’s Co-Owner and President, Natalie Cilurzo, shares in Kimmich’s relief. “I think this is a good change for our industry,” Cilurzo says, referring to the extinction of the white whale (beer). “There is such a thing as being a bit too fanatical about beer, driving some people to behave very badly. After all, it is just beer!”

In most circumstances, “it is just beer” would be treated as heresy. This is one of the few times where it’s common sense, particularly in a post-pandemic culture and economy. Pliny the Younger, Russian River’s greatest claim to fame among its sterling portfolio of world-class beers, turns twenty this year, just like Heady Topper; the beer’s endurance, and the love Russian River’s patrons still have for it, leave Cilurzo and the brewery’s team feeling bashful.

“We continue to be humbled and grateful that beer consumers still travel from all over the world to Sonoma County to drink it from the source,” Cilurzo explains. Partly, it’s the twenty years. But recency bias is real, so in large part, her appreciation stems from the lasting, ugly mark that COVID-19 left on the industry.

“We thought the pandemic might change things forever, with consumers losing interest in attending beer releases in general,” Cilurzo admits. “But, thankfully, that hasn’t been the case. Seeing people continue to show up year after year is truly something we never take for granted.”

Photography courtesy of Russian River Brewing Company

To an outsider, the temptation to attribute the showing up to Pliny the Younger’s reputation is strong; with a beer like that on your slate, drawing crowds through thick, thin, and an unprecedented viral outbreak seems pretty easy.

Cilurzo takes a different view. It isn’t beer devotees who seek Pliny the Younger. Rather, it’s the uninitiated. “I believe that most beer enthusiasts and craft beer consumers, in general, have a pretty solid knowledge of our broader portfolio of beers including both Plinys, Blind Pig IPA, STS Pils, Happy Hops, any or all of our sour barrel-aged beers, and more,” Cilurzo says. “If someone were to only know us as the brewery that makes Pliny the Younger, my sense is it would likely be a casual beer consumer or someone who has never heard of us before.”

She anecdotally refers to instances of folks waiting in line for bottles on behalf of family or friends and caught off their guard by the event of a Pliny release. “Shame on said family member or friend for not giving them a heads up!” Cilurzo says. At least the location’s lovely enough to make the wait tolerable.

The genial atmosphere she ascribes to each Pliny drop might help a little, too. “The release itself has become a bit of a reunion not only for our guests but also for us and our staff,” Ciluzro points out. In a way, that makes Pliny the Younger something like a far-flung family member you only get to see every so often, and whose arrival is an occasion worth celebrating. Absence makes the heart grow fonder.

’Tis The White Whale Season

Photography courtesy of John A. Paradiso

Between Windsor and Burlington, in St. Louis, MO, Perennial Artisan Ales’ Co-Founder and Brewer, Phil Wymore, takes the opposite view of Cilurzo regarding the brewery’s star offering: Abraxas, one of the highest-rated American imperial stouts in the country.

Once upon a time, an Abraxas release felt like an occasion similar to a Pliny the Younger release. “It’s probably become a little bit less of that,” Wymore admits. “I think that a lot of the white whale producer-type breweries have all experienced this, right? Having a beer like that has put them, or us, on the map and has allowed us an avenue of success to grow our breweries. Then all of a sudden you’re in a position where you are able to supply it a little bit more.”

Economics 504 tells us that increased supply decreases demand. The timeline Wymore draws here should, by that wisdom, end in Abraxas losing status. But that hasn’t been the case. Instead, the bump in supply has led to a shift in philosophy on Perennial’s end. “Some breweries might find that the supply and the demand hit this intersection where you might intentionally produce an amount to just keep it special,” Wymore says.

Unlike a Heady Topper, a beer that to the average Vermonter is basically mother’s milk, Abraxas is now firmly anchored to Perennial’s release calendar. “What we’ve done is, we’ve just capped it as a seasonal thing,” Wymore explains. “We’re going to start producing it in maybe late September, early October, and it’s going to come out in late October, around Halloweenish time —something like that.”

Missouri, like Vermont, has distinct seasons, and Abraxas suits fall—when football hangs in the atmosphere Missourians breathe and hearty, rich crockpot dishes are a Sunday staple. Wymore’s perspective on Abraxas makes perfect sense. But he’s quick to add that seasonality is what works for Perennial, rather than a superior way of approaching Abraxas, and white whale beers in general, in this new era of craft brewing.

“I think keeping it seasonal for us has been the right way to not ever oversupply it,” Wymore says. Make a defined volume of Abraxas; get Abraxas out to customers; move on with the brewing schedule.

“Never Rest On Your Laurels”

Photography courtesy of The Alchemist

“Moving on,” of course, doesn’t signify moving on from the white whales themselves. Any brewery in the world would kill for association with a highly reputed beer synonymous with the brewery’s name. “Who wouldn’t want a flagship beer like Heady Topper?” Kimmich says, not at all biased in favor of his favorite beer. “We’re proud of it. We created it, from the bottom up between the art and the beer itself, and the execution of the beer consistently year in and year out.”

Kimmich refuses any appeal to conceit. “We’re not in it for [having] my ego stroked,” he points out. He’s happy with The Alchemist and Heady Topper being seen, if only by a percentage of visitors or industry types, as one and the same. “If that’s what you think, that that’s the only thing we do, fine,” Kimmich says with a congenial tone. “If you ever stop by, you’ll see that that’s not the case.”

Wymore and Cilurzo echo Kimmich’s sentiment. “I think that it’s a blessing,” Wymore says. “It’s kind of like having a video go viral, or writing a hit song.” Like Kimmich to Heady Topper, the Perennial team takes great pride in Abraxas—but they’re equally so of the rest of the brewery’s output. “I know our guys are passionate about all kinds of other styles,” he continues. “But we don’t find it annoying to be known for [Abraxas].”

He’s aware of the intrinsic recognition between a white whale like Abraxas and the Perennial name. “It was a little interesting at first, traveling around to other markets,” Wymore reflects. “We started to expand, and we go to festivals all the time, and that’s what we’re known for.”

As Cilurzo points out, “It’s okay to be known for something you do very well. But it is important not to rest on your laurels and think that one beer or beer style will always be popular.” Even with its well-established stature in the craft beer community, Russian River continues to innovate, trying new techniques and styles, and testing the boundaries of its own beer.

Pliny the Younger is a great example: Russian River has double dry-hopped the beer since well before it was cool. “In the years it wasn’t double dry-hopped,” Cilurzo says, “it was quadruple dry-hopped!” Talk about being ahead of the curve. In fact, that sort of forward-thinking may be even more critical for breweries like The Alchemist, Russian River, and Perennial. It’s good to have a marquee offering. That’s one bulletproof way to spread word of mouth. But it’s even better to push the envelope and show that your brewery is more than the iconography.

“If you ever care to explore what we do a bit more beyond that,” Kimmich says, not only of The Alchemist but all white whale brewers, “then you’ll see everything else.”