Shop

What Is Umqombothi? The Thousands Year Old African Beer Style

An untold beer history.

Looking for More?

Mix sorghum and maize with warm water. Let the mixture sit overnight, bringing it to a boil the following morning. Add a starter—often more sorghum or yeast—and leave in a warm place to ferment for a few days. Strain off the grain, but not too much—you want a porridge-like consistency—and serve. Those are the basics for making Umqombothi.

But Umqombothi is anything but basic. And unlike so many of the modern beers that we drink today.

A sorghum-based fermented beverage indigenous to Africa, Umqombothi dates back thousands of years and is typically brewed by women inside the home for special occasions.

“I normally say it’s like wine, but a thick one,” says Thembisile Ndlovu, who started her own Umqombothi business after placing in the top three of an Umqombothi Brewing Competition held in South Africa in 2021. “Something like a soft porridge, but it has a bitter taste.”

Apiwe Nxusani-Mawela, who started that Umqombothi competition, cautions that you can’t constrain Umqombothi with rigid definitions like the Beer Judge Certification Program (BJCP) guidelines, for example. Trust her; she tried, “but then I realized it’s too broad to try to box it because it all depends on preferences and what you’re brought up to make,” she says.

From the Xhosa tribe, Nxusani-Mawela grew up in the Mgomanzi village in the town of Butterworth in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. While they call this beer style Umqombothi in the Xhosa language, Nxusani-Mawela says there are many different names based on what tribe you’re from in Africa or South Africa, which has eleven official languages.

And for all intents and purposes, every community and perhaps every family brews Umqombothi a little differently.

“What fascinates me is that it’s the same but different at the same time,” she says perplexingly.

Nxusani-Mawela, a microbiologist who worked at SAB (South African Breweries) after university and trained as a brewer with the Institute of Brewing and Distilling, couldn’t help but try to codify brewing Umqombothi. She started to question what was happening scientifically when she watched her family brew at home.

“I was explaining why we measure pH, why we measure temperature,” says Nxusani-Mawela. “My mom actually wanted to chase me out!”

Learning to brew Umqombothi and spread that knowledge became an obsession for Nxusani-Mawela. “I fell in love with the idea of bringing rebirth within my space, which is brewing,” she tells me.

Now the brewmaster of Tolokazi, a sorghum beer expert, and the founder of Brewsters Craft, Nxusani-Mawela considers brewing Umqombothi an “indigenous science that has been passed on.” There aren’t any guidelines or rulebooks; there are tentpoles by touch and feel.

“My mom will tell you that you feel the temperature with your elbow, and by feeling it, you know if it’s too hot or too cold,” says Nxusani-Mawela. “That’s something that isn’t written in any book. You just know.”

So, How Do You Brew Umqombothi?

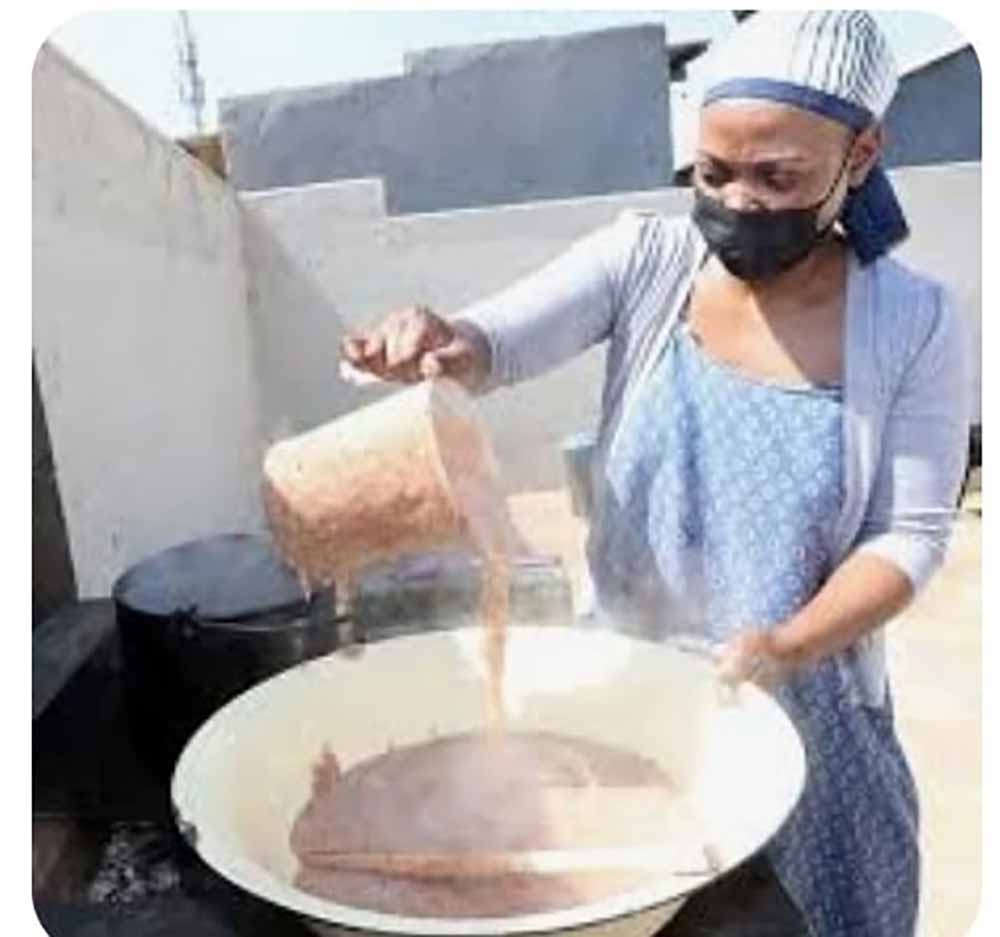

Photo supplied by Apiwe Nxusani-Mawela

As we said, everyone brews Umqombothi a little differently.

Nxusani-Mawela describes her process to me. She uses a one-to-one ratio of malted red sorghum and white maize (at home, she usually uses yellow maize, but they only have white maize available in Johannesburg; Whichever you choose to use will affect the taste profile differently).

You mix those two together with five liters of lukewarm water. “Not hot, just warm,” says Nxusani-Mawela, and leave it overnight. “I’ll probably do the mixing in the evening around 5 p.m. and then let it sit overnight till tomorrow morning. That’s where you’re having your lactic acid fermentation.”

If you want your Umqombothi to taste more tart, Nxusani-Mawela says to ferment the mixture longer before proceeding to the next step.

In the morning, Nxusani-Mawela boils the mixture for an hour, adding more grain as she stirs. “This is similar to clear beer making to make sure you drive off the volatiles,” she says. “Obviously, the key is to make sure it doesn’t burn.”

After an hour, Nxusani-Mawela takes everything off the stove, cooling the liquid to room temperature. “If I wake up at 6 a.m., so obviously I prepare to get to work, I boil, then I’ll leave it in the morning. Then, if I’m around midday, I’ll start mixing, but if I’m not around, I’ll leave it the whole day,” she says. “When I come back in the evening, I mix it with room-temperature water. You’re just loosening it up to allow for fermentation.”

Here, Nxusani-Mawela explains that you can either add more sorghum (maybe half a kilo) or pre-purchased yeast packs. “That’s basically your starter,” she says.

If you’re not in a hurry, you can just use sorghum and the natural organisms on the grain to kick-start fermentation. “It will be slow,” says Nxusani-Mawela. If you’re looking for a quicker fix, “while you’re boiling, add sugar … so that by the time you’re ready to mix, you’ve got a starter culture,” she says. “But basically, you need some form of yeast coming from somewhere to allow for the fermentation.”

Now, you want to keep the mixture warm because it’s fermenting with an ale yeast. “In winter, we normally either put a blanket on, put it by the windows so it catches the sun, or put a heater on,” says Nxusani-Mawela. “In the villages, they used to put it in the room with the wooden floor fire, just to make sure the room was warm.”

The Umqombothi ferments for about two days before you strain off the grain. “Not until it’s crystal clear,” says Nxusani-Mawela. “You’re just removing the thick particles. You still get a bit of the finer particles, which gives you the body because you don’t want it to be too thin; it gives you that complexity in the body and mouthfeel.”

Some like to ferment Umqombothi longer, creating a higher-alcohol beer with less carbonation that is less “porridge-like,” according to Nxusani-Mawela. “It goes with taste preference.”

After sieving, you leave the Umqombothi for about two to three hours before serving. “In the village, you would wake up very early in the morning and start the sieving so that by the time people arrive around 8 or 9 a.m., you’ve allowed for your rest,” says Nxusani-Mawela.

You need to consume the Umqombothi within two or three days at most because otherwise, “you can start having your acetic bacteria, and then you start getting vinegar sour, and you want a more clean, lactic sour,” she says.

Photography courtesy of Thembisile Ndlovu

Ndlovu, who learned to brew Umqombothi from one of her mother’s friends, follows a similar process but adds a somewhat intangible component to her recipe.

“Spiritually, if you’re not okay, it won’t ferment,” she warns. “But the first time I brewed it, I was so excited, and it came out okay. Everybody was excited to drink my Umqombothi and was drunk and happy!”

Based on feedback from her first batch, Ndlovu entered the Umqombothi Brewing Competition with her recipe.

She explained that she mixes maize meal and umthombo (sorghum) before adding warm water to make a paste.

Photography courtesy of Thembisile Ndlovu

Next, she differs slightly from Nxusani-Mawela, adding Chibuku, a shelf-stable sorghum-based beer. “I add a little bit of Chibuku for fermentation,” Ndlovu clarifies. She leaves the fermenting mixture for two days before cooking what she calls her “soft porridge.”

After cooling, Ndlovu adds more raw umthombo and a little warm water, covering everything with a blanket to ferment overnight.

In the morning, she strains the Umqombothi, saying, “It’s ready to drink!”

Overall, Ndlovu, who now brews consistently once a week, says it takes a full five days to make her Umqombothi.

Because the Umqombothi has a bitter taste at this point, she says you can enjoy it plain or add a little ice cream to make it sweeter.

“When tasting my Umqombothi, people said you could do this for athletes and people who go to the gym,” she explained. “You can give them Umqombothi with ice cream so that it will be like a smoothie.”

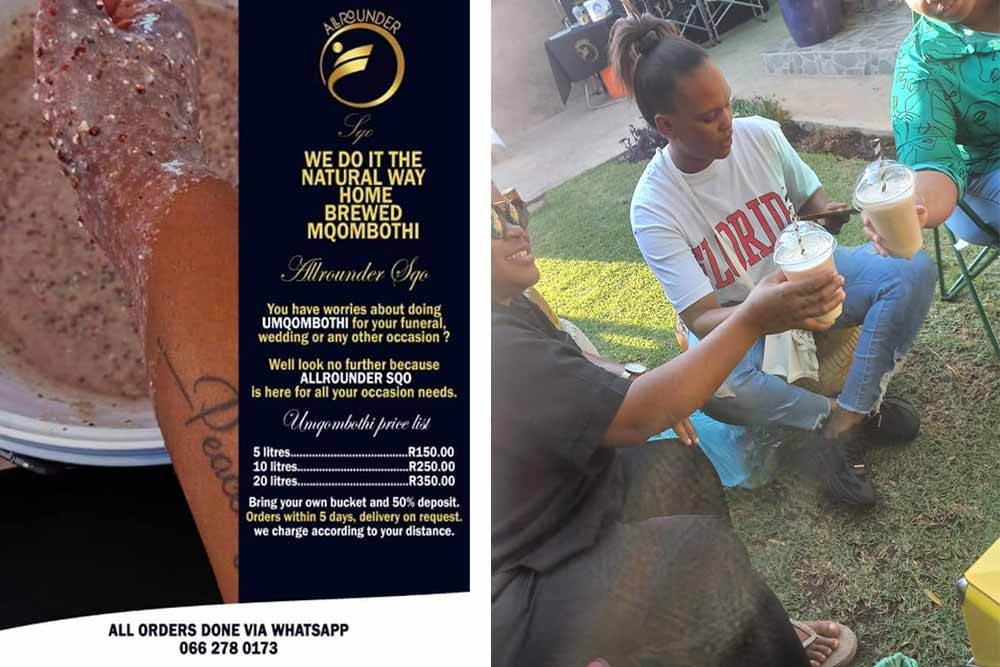

After placing highly in the Umqombothi Brewing Competition, Ndlovu started her own business, bringing her homebrewed Umqombothi to the public.

She sold her Umqombothi to pubs, proposing them to complement Mogodu Mondays, a specific day of the week when restaurants and bars serve traditional food. She pitched adding her Umqombothi to the menu as a traditional drink complement. “Everybody was excited because you can’t find Umqombothi in the restaurants,” she tells me.

Although she no longer brings her Umqombothi to restaurants, Ndlovu now hosts monthly events where people can learn about the style and drink her recipe.

What Does Umqombothi Taste Like?

Photo supplied by Apiwe Nxusani-Mawela

Again, it depends on who you talk to since everyone brews their Umqombothi a little differently.

“Even though the ingredients are the same—all using maize and sorghum, malted sorghum, malted maize—the processes slightly differ and the tastes differ,” explains Nxusani-Mawela. “Some people want it more sour. That means your souring process is a bit longer. Some people want it creamier. That means your ratio of sorghum will differ because the more maize you have, the creamier it’s going to be.”

With various commercial brands available, the type of sorghum and maize you choose to use also affects the flavor.

For example, Ndlovu, who earned the nickname Queen of Umqombothi after winning the competition and starting her business, likens Umqombothi to a drink called Mageu, a non-alcoholic fermented maize-based beverage in Southern Africa that’s sort of like kombucha.

Nxusani-Mawela’s recipe isn’t as tart because she’s not a fan of sour beers. “It’s got a nice tinge of sourness, but it’s not overpowering,” she says. “It’s not too creamy, but it’s got your grainy backbone, like a nutty, grainy flavor. … It’s not water; it’s like a medium body.”

Low in alcohol, Umqombothi is meant for easy drinking.

Now, during Nxusani-Mawela’s Umqombothi homebrew competitions, she gives these instructions to the judges: “The key thing to look at, obviously, we want a clean sour. The intensity of the sour can vary, but as long as it’s a clean, lactic sour,” she says. “We don’t want acetic sour, and we don’t want burnt notes.”

She continues, “Is it clean? Is it drinkable?”

When Do You Traditionally Drink Umqombothi?

Photo supplied by Apiwe Nxusani-Mawela

Historically brewed in the home, Umqombothi appeared at traditional ceremonies.

“You drink Umqombothi when there’s a wedding, a funeral, only those traditional ceremonies,” says Ndlovu.

Nxusani-Mawela agrees that it’s mainly for special occasions. “Whenever you’re having a ceremony, whether there’s a new birth, a death, a graduation party, or a wedding,” she says. “You brew it every time you want to connect to the ancestors.”

For example, after graduating from university, Nxusani-Mawela’s father called her back home to watch her mom and aunts brew Umqombothi in a thanksgiving ceremony. “For blessings out of high school, university, just things going well,” she explains.

Have Craft Breweries Tried Making Umqombothi?

Photography courtesy of Soul Barrel Brewing

The beauty of Umqombothi lies in its heritage. “It’s an unbroken chain of brewing tradition whose native form is still preserved and made today,” says Nick Smith, founder and brewer at Soul Barrel Brewing in Franschhoek, Western Cape South Africa, who first learned about the traditional fermented beverage when he opened a brewery in 2017. “I don’t know anywhere else in the world that has a traditional [beer] going back so historically and brewed using the same methods.”

He continues, “From a beer culture standpoint, it’s completely fascinating because it’s an indigenous, untold-to-North America beer story … using pre-industrial revolution methods to make a beer that’s been around for potentially hundreds or thousands of years.”

Essentially, Smith thinks of Umqombothi as “the original homebrew,” existing thousands of years before we ever heard the names Ken Grossman or Jim Koch.

For that reason, not many craft breweries have made their own versions. To do so, you must understand and respect the Umqombothi you’re making entirely. And have access to malted sorghum.

Photography courtesy of Soul Barrel Brewing

After trying a few versions, Smith became fascinated with Umqombothi. “It was unlike any beer I had before,” he says. “First of all, it’s not really carbonated. … It’s very creamy from the sorghum. I tend to get chocolate notes from the creaminess, not overtly but subtly.”

He keeps going excitedly, “There is an earthiness to it that is sometimes very difficult for people to get, which comes from the lacto … there is a cheesiness, depending on how you brew it, how much lacto growth [it’s] getting, and the temperatures and the times. It can be an earthy off-flavor by commercial standards, so that’s unique.”

Perhaps the simplicity and yet complexity of Umqombothi appeal to Smith because, at Soul Barrel, he primarily makes unique interpretations of barrel-aged, wild-fermented beers.

Eventually, he wondered, “How can we combine these two beer cultures and draw on their common thread?”

Without any experience making Umqombothi himself, Smith teamed up with Nxusani-Mawela, brewing Umqombothi traditionally up until the last step. “Instead of drinking it, we then do a secondary fermentation in the barrel with a Brett wild-fermented beer,” he explains. “Ours draws inspiration from beer culture, looking at similarities in structure and flavor in American or European wild-fermented beers and combining the two to make something unique and new.”

According to Smith, the beer called Wild African Soul turned out fantastic. “It was just such an interesting beer,” he recalls. “You had this grain complexity coming through you don’t get from anything else, a very clean lemon-type acidity with the pepperiness of Brett, and an almost honey-type ester malt yeast flavor; it was so good.”

Photography courtesy of Soul Barrel Brewing

It’s one of Soul Barrel’s full-time beers now, with Smith also making variations throughout the year.

And once or twice, Soul Barrel makes traditional Umqombothi, serving it on a particular Saturday.

“That’s always fun because we get people talking about it, realizing this really cool beer thing is happening in South Africa,” says Smith, “and no one is talking about it.”

Until now.

The Future of Umqombothi: An Interesting Dilemma

Photography courtesy of Thembisile Ndlovu

Umqombothi stands at a crossroads, according to both Nxusani-Mawela and Ndlovu.

A beverage that has traditionally been brewed in the home in Africa for centuries, Umqombothi has a perception amongst younger cultures as anachronistic.

“The consumer is changing,” says Nxusani-Mawela. “The young people don’t want to [drink Umqombothi] because it’s seen as backward or not moving on with the times.”

For the most part, you won’t find Umqombothi in pubs. United National Breweries does have some sorghum beer products on shelves—Ijuba, Tlokwe, Chibuku, Leopard Special—but up until a few years ago when Ndlovu started selling her Umqombothi and Soul Barrel brewed a version, no “craft” Umqombothi existed.

Ndlovu’s business has been one of the only ones that has tried to attract a younger generation. “People are too lazy to brew Umqombothi, so I’m the lady brewing it for them!” she says proudly. “I’ve made it a public thing that you can access anytime you want. I’ve added Umqombothi into the entertainment industry.”

Photography courtesy of Thembisile Ndlovu

With Ndlovu’s creamier, smoothie-like version packaged in attractive cups, she feels the younger generation is more interested in drinking it. “Before, they were not interested in drinking Umqombothi because they thought it was for older people, not us,” she explains. “I’m closing that gap.”

After dedicating a good part of her adult life to Umqombothi, Nxusani-Mawela also hopes to create a bridge between the past and the future.

“We can merge the old with the new to create a new world, something that will move us forward, but having a bit of the past so that we never forget where we come from as we embrace who we are currently and who we will become in the future,” says Nxusani-Mawela, who continues to runs her Umqombothi Brewing Competition every year in September, which is Heritage Month in South Africa. “My worry is that, if my generation doesn’t care about [Umqombothi], and we are all in the urban areas, it’s going to be lost. How do you make sure that the product itself continues to be interesting and exciting for people?”

Nxusani-Mawela’s idea is to use tourism to get people stoked about the ancient beer style. “If you were to travel to South Africa, I’m sure you would want to try some,” she says. “But where do you find it?”

Nxusani-Mawela proposes linking up with tourism boards and local authorities to use Umqombothi to create new avenues of employment and promote tourism, African cuisine, and drinks, “where people can actually enjoy the food and have a drink indigenous to Africa,” she says.

Ndlovu has a vision even bigger. “My dream is to go global.”